On the eve of the opening of his New York show at the Australian Consulate-General, Matthew de Moiser spoke to the Art Life about the seduction of the plastic surface, making beauty and suburban utopia…

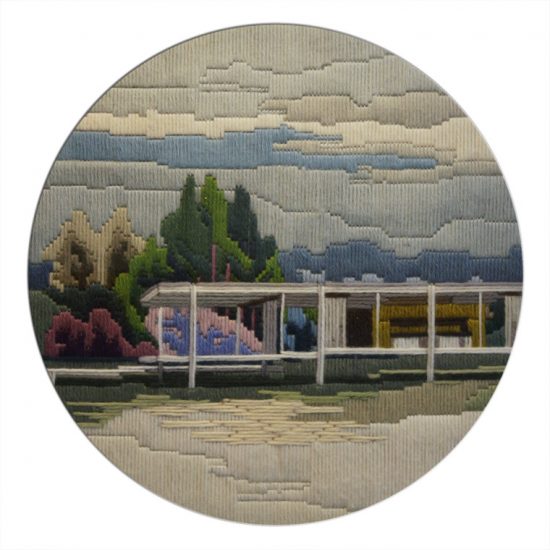

Matthew de Moiser, Farnsworth House, long stitch embroidery, 47x47cm.

Matthew de Moiser, Composite 1, Oil paintings on ply, 25x18cm

Andrew Frost: In the past you’ve explored the relationship between the pictorial and material qualities of painting by using a variety of media to make images, from long stitch embroidery to make homely renditions of classic architecture, to cut up op-shop landscape paintings for wall objects that sit somewhere between an object and a picture. Your most recent work uses laminex on board to produce what look like very pop-inspired landscape works. Could you talk a bit about where this latest body of work has come from and some of the ideas behind it?

Matthew de Moiser: The laminate series of works actually came from an earlier body of work made from re-used Ikea furniture parts. The common thread though, the thing that brings all these different bodies of work together is the use of everyday objects and materials as a way of re-framing and re-contextualising the ordinary everyday world around us. I use the materials I do because they have a kind of power. They speak about the ordinary everyday here and now. They are vessels that carry memories and evoke emotions, sometimes tapping deep into the viewer’s subconscious. Usually, this happens in spite of me – it’s what people bring to the work that matters. I just need to leave enough room in the work for this to take place. The laminate lends itself to this because it’s such a challenging material to work with. So the imagery tends to be more pared back leaving room for the viewer to overlay their own experiences.

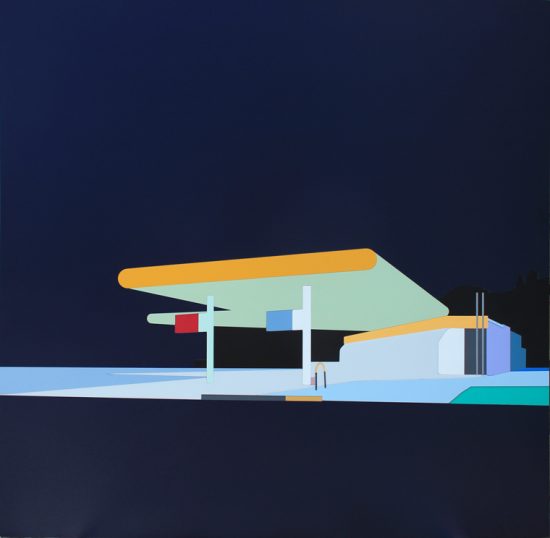

Matthew de Moiser, Servo No. 3 (state 7), laminex on board, 60x60cm

AF: The first artist that came to mind when I looked at your ‘laminate paintings’ was Ed Ruscha, and there seems to be a similar kind of conceptual interest for you in the way a picture is made and ‘read’. Was there a specific starting point for you?

MdM: It’s funny you should say that, I’ve actually just requested access to the MoMA archives to see Ruscha’s work when I’m in New York. He’s certainly an influence and I’m interested in seeing how he deals with the absence of surface detail and texture in his prints.The laminate is similar in that there isn’t any textural detail as such, so there needs to necessarily be an emphasis on reduction, composition and colour instead. In Ruscha’s Standard series of prints – you know the service station ones – the perspective is blown out and exaggerated. Without having texture to rely on, I have to emphasise composition too.

Mattew de Moiser, Mount Pleasant Street (state 6), laminex on board, 60x60cm

AF: I saw some of your work at your last show in Sydney and one of the things that really struck me was how seductive the surfaces of the works are. Is this something that you’re interested in the way the viewer responds to the work?

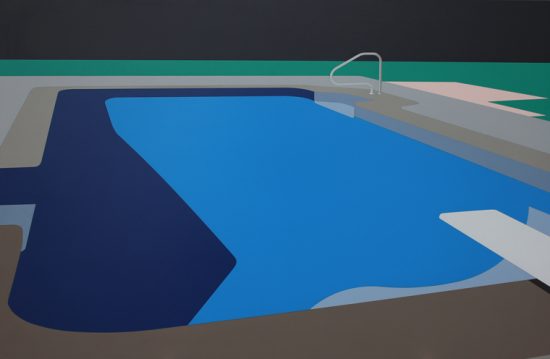

MdM: I love the paradoxes of this material – that what is essentially a mass produced building product can somehow transcend itself and become seductive, sublime even. This is the aspect of this work I’m most interested in and will be exploring further in the upcoming April show at James Makin Gallery. I guess there is a similar paradox in the places I’m depicting too – suburban servo’s, houses, backyard swimming pools and freeway overpasses – you know, generic vernacular architecture that can be bland and beguiling at the same time – like the lovingly manicured front lawn of an otherwise unexceptional suburban house.

Matthew de Moiser, Creek overpass, laminex on board, 105x65cm

AF: How do you regard the images in the Laminate Series? For me there’s a utopian edge to the work insofar as they don’t seem specifically critical of these places and spaces, yet at the same time, in images of an overpass, a petrol station or 7/11, there’s a also ‘beautifying’ effect too…

MdM: I grew up in Melbourne’s outer eastern suburbs which back then was the frontier – the very edge of the city where the housing estates gave way to paddocks and market gardens. To me this work sits somewhere between Howard Arkley’s celebration of suburbia and Robin Boyd’s contempt for it. I’m trying to capture some of the complexity of this contested space; yeah the hyper-coloured palette could represent a utopian view of the great Australian dream. But the laminate material on the other hand is also a thin plastic veneer used for protection and ornamentation. It suggests isolation, boredom I suppose and keeping up appearances. My last exhibition at Flinders Street Gallery was called Face Lift – I was hoping to get a cosmetic surgeon to do the opening speech but we couldn’t find anyone. I was thinking about the absence of textural detail in the laminate and how it is a bit like botox, removing the visible signs of ageing, wear and tear. Like a TV personalities’ impossibly white smile, the laminate can be dazzling but slightly unsettling at the same time too.

Matthew de Moiser, Without a splash (state 4), laminex on board, 86x56cm

AF: You’ve got a show coming at the Australian Consulate-General in New York. What are your thoughts on how the work willl sit in that kind of context?

MdM: Australia and the US have a shared suburban experience. After World War II the suburban prototype as we know it emerged first in the United States where the rising popularity of the automobile, the growth of the urban road network and changes to town planning regulations saw the suburbs grow rapidly. In many ways the US was our suburban prototype and it is also incidentally the birthplace of Formica and the decorative laminate industry. The laminate gives my images a kind of generic familiarity too, making their origins ambiguous and dependent on the viewer. So for example a freeway exit ramp can be interpreted as the Monash Freeway by someone from Melbourne, the Westlink M7 if you live in Sydney or commuting to work on the Interstate I-105 if you’re from Los Angeles. The work will be shown alongside photographs by LA based Australian artist George Byrne. There is a similar reductive process going in George’s work but in a completely different medium. So it will be interesting to see how the works speak to one another and how the audience receives them.