Luise Guest on the ‘Chinese Bible’ and ‘Go East’ and other works from the Gene and Brian Sherman Collection of Asian Art…

To title an exhibition of contemporary Asian art ‘Go East’ might seem deliberately provocative, given the geographical reality that Asia is not, in fact, to our east. It hints at Orientalism, at ‘Otherness’, at post-colonialism, as curator Suhanya Raffel acknowledges in her excellent catalogue essay. But it also acknowledges another reality: since the 1980s, despite many a political and diplomatic hiccup along the way, Australia has, in fact, turned to the metaphoric and cultural (if not the geographical) east.

Yang Zhichao

Chinese Bible, 2009 (detail)

3,000 found books

Dimensions variable

Image courtesy: The Gene and Brian Sherman Collection, and Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney

Photo: Jenni Carter, AGNSW

The history of our engagement with contemporary art from Asia is filled with significant exhibitions, strong private and public collection programs, and cultural exchanges, of which ‘Go East’ is an important example. Since the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation’s first commissioned project with Ai Weiwei in 2008, many of these discourses have been instigated by Gene Sherman. Through subsequent projects Australian audiences have been introduced to works by Chiharu Shiota, Charwei Tsai, Yang Fudong, Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan and Dinh Q. Le, to name just a few. ‘Go East’, an exhibition of works from the Gene and Brian Sherman collection at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, features these artists and others from China, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, Tibet and Vietnam. It presents compelling evidence that an artistic ‘pivot to Asia’ will continue to enrich, provoke, and delight audiences.

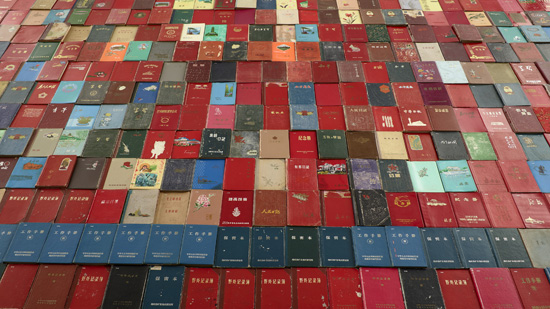

Meanwhile, at the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Paddington, Yang Zhichao’s ‘Chinese Bible’ fills the space recently vacated by Shaun Gladwell’s watery ‘Lacrima Chair.’ A sea of red, interspersed with flashes of blue, yellow and green, ‘Chinese Bible’ comprises three thousand personal notebooks and diaries collected by the artist in Beijing’s Panjiayuan ‘Dirt Market’, revealing a hidden history. Showing in tandem with ‘Go East’, the work represents the tsunami of change weathered by ordinary Chinese people over the fifty turbulent years from 1949 to 1999. Exhibitions, Gene Sherman told her audience at the opening of ‘Chinese Bible’, are “primary sites for the construction of art history. Exhibitions tell the story of art. They reveal untold or forgotten aspects of history – not just art history – and they shine the light on social injustices. Exhibitions are where artworks meet audiences.”

Yang Zhichao

Chinese Bible, 2009 (detail)

3,000 found books

Dimensions variable

Image courtesy: the Gene and Brian Sherman Collection, and Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney

Photo: Jenni Carter AGNSW

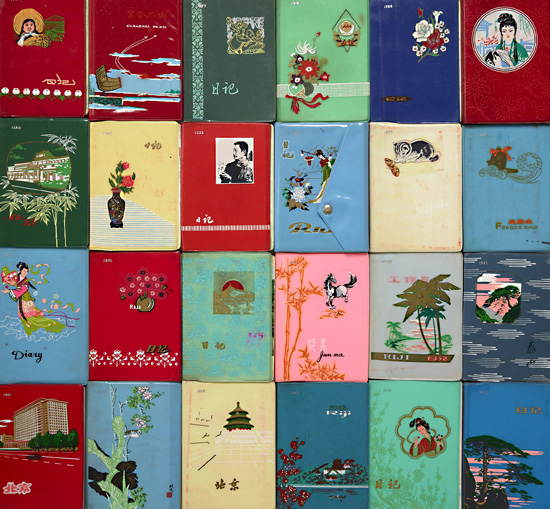

These humble notebooks and diaries, rescued from oblivion, washed and presented as found objects, are filled with self-criticisms, transcribed passages of compulsory ‘Mao Zedong Thought’, mechanical diagrams, even (forbidden) personal reflections, poetry, knitting patterns and recipes. Laid out in symmetrical rows on a raised platform, the almost uniform red of their covers presents an allusion to the modernist grid – another kind of failed utopian vision. Their cover designs reflect periods of recent history, with pictures of animals, temples, traditionally costumed characters, and dancers disappearing in the years of collective madness between 1966 and 1976, when the Cultural Revolution made every element of an individual’s dreams, desires or memories suspect and taboo. Those covers are plain red, or adorned with images of Mao.

Better known for provocative performance works involving bodily mutilation and even surgery (most notably having tufts of grass from his home province surgically implanted in his back) Yang has found a new calm and quietness. Like other transgressive artists of the period such as Zhang Huan (whose ‘Sydney Buddha’ featured at Carriageworks over the summer) Yang Zhichao appears to be reflecting on his own and China’s history. I asked the artist about this change in his practice. “It relates to the introduction of performance art into China – in 1989 it was a very new thing, and was introduced into China from outside,” he said. “From 1995 to 2005 it was kind of a ‘golden age’ of Chinese performance art – it was an art form that put the artist in opposition to a variety of things: to society in general, to living conditions, to governmental regulations, and of course to the artworld itself. It was such a meaningful practice. In the period 2005 – 2015 there has been significant change in China that has also contributed to a change in art practice. Looking back over the last ten years… in general it has changed to a less confrontational mode.” And, he added, somewhat ruefully, “Also, artists have aged!”

Chinese people of older generations are pragmatically stoic about the past and generally express little desire to revisit its privations or terrors. In the rush to modernisation and globalisation, much of the recent past has vanished. By finding the diaries (on sale due to their value as scrap recycled paper), carefully washing them, and presenting them as an installation, Yang Zhichao poignantly reconstructs an alternative history: a vernacular narrative of the small, the domestic and the hidden. Curator Claire Roberts lived and studied in China during those years. She told me, “Having spent time myself in China in the 1970s and 80s before its radical physical and economic transformation, for me it’s very moving. Even just by looking at the patina on the covers of the diaries you can see history unfolding before your eyes. These three thousand diaries each represent a fragment of the actual lives of individual people. We can appreciate it as a contemporary artwork, but also it opens up all sorts of insights into how individual lives intersect with the big historical movements.”

Zhang Huan

Family Tree, 200

C-type prints. Suite of 9 images

Edition 2/3

227 x 183 cm (Framed)

Image courtesy: The Gene and Brian Sherman Collection, and Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney

Photo: the artist

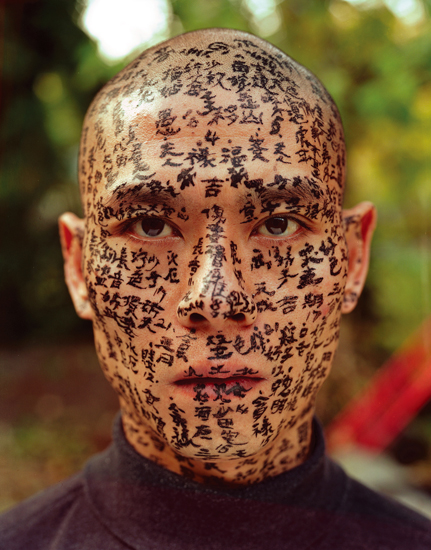

Works at the Art Gallery of New South Wales reflect on these convergences of history too. Zhang Huan’s ‘Family Tree’ reveals the artist’s own face, one image after another, gradually painted with black Chinese characters until his individual features are completely obliterated, covered over by culture, conformity and duty. Created during a period of artistic exile in New York, the accretions of Chinese text over the artist’s face express something of the agonising homesickness, identity confusion, and doubt afflicting diasporic artists.

Ai Weiwei is represented by two works in this show. ‘Overcoat’ is one of Ai’s Duchampian ‘readymades’, a padded People’s Liberation Army khaki overcoat of the kind now worn mainly by the poor and elderly in China. Signed by the artist, it is accompanied by two photographs of a young man wearing the coat. It was one of a number of coats given by the artist to a charity for the homeless by the artist, who liked the idea that the recipients had no idea they were wearing an artwork. The other is a newly commissioned work. ‘An Archive’ is a collection of the artist’s blog posts, presented in the form of traditional Chinese books, and representing his resistance to the censorship and constraint that still sees the artist confined to Beijing without possession of his passport, constantly under surveillance. This collection, and his recent installations in San Francisco, ‘@Alcatraz’, alludes to global concerns about political dissent, beyond China.

Thai artist Navin Rawanchaikul’s ‘There is No Voice (3)’ presents discarded medicine bottles, arranged within a vitrine. Each bottle contains a rolled-up black-and-white photograph of a senior citizen from his own community of Chiang Mai. Presented as if they are scientific specimens in a dusty natural history museum, the work captures the individual and asks us to question our attitudes to aging and mortality. Only one still image from Dinh Q. Le’s extraordinary and powerful installation, ‘Erasure’, reminds us of how the Vietnamese-born artist connected the boat arrivals of early colonists to Australia with more recent and politically contentious ‘boat people’. The image of a shipwreck evokes sensations of melancholy and loss, and the artist’s constructed image of a sailing ship burning on a desolate shore is particularly resonant given recent headlines, and the tragic loss of so many lives at sea.

Lin Tianmiao, Badges 2009 White silk satin, coloured silk threads, gold embroidery frames made of stainless steel; sound component: 4 speakers with amplifier. Dimensions variable, diameters range from 25 cm – 120 cm, 266 badges total. Image courtesy: The Gene & Brian Sherman Collection, and Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney. Photo: Galerie Lelong, New York.

In the gallery vestibule Lin Tianmiao’s, Badges fill the space. Steel embroidery hoops hang from the ceiling, swaying in the slightest breeze, turning to reveal Chinese words meticulously embroidered on silk, all describing women. This ongoing project stemmed from Lin’s realisation that the classical Manchu Kangxi Dictionary contained only two or three hundred words describing women and the roles they played in society, mostly obsolete terms for courtesans and concubines. Today, new words are coined every week, reflecting dramatic social change. From ‘Phoenix Lady’, ‘Reliable Lady’, ‘Fox Spirit’, ‘Sheng Nu’ (leftover, unmarried woman over 27) or ‘Xiao San’ (‘Little Third’, or popular slang for a mistress), Lin Tianmiao has sought out the new slang terms that apply to women, disseminated via the internet. The work is beautiful and tranquil, but possessed of a slyly subversive intent. Lin Tianmiao reflects on the difficult territory traversed by women in a new China, confined even today by Confucian norms of filial piety and patriarchal authority, contradicted by unrelenting social transformation.

*** Local Caption *** 12/05/2015 Installing of Jitish Killat, Public Notice 2 (14 May – 26 July 2015) in the Entrance Court of the Art Gallery of New South Wales as part of Go East, The Gene & Brian Sherman Contemporary Asian Art Collection

Jitish Kallat’s Public Notice 2 (2007), a vast field of bone-shaped letters spelling out Mahatma Gandhi’s famous speech on the eve of the 1930 Salt March, dominates both sides of the gallery’s entrance court. Together with ‘Chinese Bible’ at SCAF this work reveals an underlying narrative of the exhibition – and indeed of the collection: the collision of private and public lives, the impact of historical events on ordinary people, and the tensions between internal and external worlds.

Go East: The Gene and Brian Sherman Contemporary Asian Art Collection, curated by Suhanya Raffel, Art Gallery of New South Wales, till 26 July 2015. Yang Zhichao: Chinese Bible, curated by Claire Roberts, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, SCAF Project 26, till 1 August 2015.

Jitish Kallat: Public Notice 2, Curated by Suhanya Raffel, Art Gallery of New South Wales, till 5 October 2015

Gene and Brian Sherman have assembled a stunning collection showing the power of contemporary Chinese art. Bravo!