Carrie Miller finds queasy memories in the paintings of Robert MacPherson…

I don’t get out much. I never have. Some of the biggest trips I’ve taken were the driving holidays popular with working and lower middle class families that my own family took when I was a kid in the early 70s.

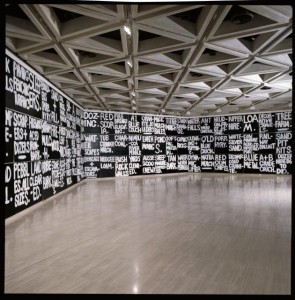

Acrylic on masonite, 156 panels, 122x95cms each.

Courtesy the artist and Yuill|Crowley, Sydney.

If one were inclined to understatement, you’d call them disastrous. Dad was resentful for being torn away from work and Mum was resentful of this resentment. These driving jaunts from our home in inner city Newcastle to rural NSW can be summed up by Dad’s dictum which he inevitably yelled at the beginning of these trips as my sisters and I sweltered and fidgeted in the back seat of the Holden: “Shut up. This is a holiday and you will enjoy yourself”.

The tension was so overwhelming that I don’t remember much except the petty arguments and the motion sickness as the sometimes harsh, sometimes idyllic scenery whizzed by.

But one image indellibly pressed into my memory is of those roadside signs advertising the fresh produce of hobby farmers or market gardeners. As a little girl I imagined the happy families who grew that produce and I idealised their handdcrafted signs. As an adult I know I romanticise them still; the reason I know this is because I’m an obsessive fan of Australian painter Robert MacPherson‘s text-based paintings and I don’t have a particularly critical perspective on why.

These works, generally executed on black board or masonite with words written on the surface in white with a common house painter’s brush, are arranged in a modernist grid in a way where the works operate successfully both individually and as a whole.

This is the type of work he has exhibited at the Cockatoo Island site of the Sydney Biennale but in an enormous four-sided cube. In the blurb accompanying the work MacPherson claims that through his practice of repainting hand-made road signs that he sees on his travels through Australia he achieves a “wonderful directness of means and an un-selfconsciousness in the use of paint often lost in so called high art”.

We can only take his word for this. But the very fact that he takes such banal, everyday ephemera and elevates it to the status of Biennale exhibit makes such a statement somewhat paradoxical. The reason I love MacPherson’s work is precisely because it romanticises the everyday – and specifically a slice of the everyday I (and many other Aussies) have romanticised in our memories.

I get the artist’s point – and even the point of critics who argue that his vision of Australia is an uncritically romantic one. But I don’t care; I’m going to keep on romanticising Robert Macpherson as one of the great Australian painters of his generation.

When I see a sign near my house that says LEARN ROCK AND ROLL I think of Macpherson. Can’t help it.