Guest blogger Luise Guest takes us on a guided tour of the studios of some of Hong Kong’s leading contemporary artists…

The English writer Fuchsia Dunlop memorably likened Hong Kong to a ‘decompression chamber’, and indeed it can function as a kind of valve between the comfortable familiarity of the west and the challenges of mainland China. Hong Kong has been something of a liminal zone since the days of the Treaty Ports and the British seizure of its harbour at the end of the first Opium War in 1842. It is, however, in all its postcolonial hybridity, a place with its own unique history, and this results in contemporary art quite unlike the current shape of art from China’s mainland. ‘China Lite’ it is not!

Carol Lee Mei-kuen, Lam Tung-pang, Wong Chung-yu and Hanison (Hok-shing) Lau are four artists who work in different forms, with different ideas informing their practice, yet there is a connecting thread which weaves its way through their work. That thread can be traced back to the colonial history of Hong Kong and the tensions resulting from its fluid, at times blurred identity: at once drawn to China and yet distinct from it. Lam Tung-pang expressed this poignantly when he told me that during his studies in London he was always described as a Chinese artist, but when he went to Beijing to set up a studio there he was considered ‘western’. These four artists question their identity, their personal and cultural histories and memories, and their place in the world. Aware and often resentful of the privileging of mainland art as an internationally recognised ‘art brand’, and knowing that western buyers want to buy art that ‘looks Chinese’ (hence the Wang Guangyi and Yue Minjun knockoffs in street markets and small galleries) and that Hong Kong galleries are only just beginning to represent local artists, they sometimes feel marginalised and excluded from art discourses. However, in the recent past they have become a stronger presence in the Hong Kong and international cultural scene. Their work reflects the hybridity and excitement of Hong Kong –a ‘treaty port’ of international exchange in the artworld, if you like.

Carol Lee Mei-kuen makes elegiac and poignant works using a most unusual technique of her own invention, reminiscent of early 19th century photographic daguerreotype or cyanotype experiments. Quite by accident, while making a daily drawing with ink on newsprint, she discovered that the yellowing of the newspaper after exposure to daylight was beautiful and, after much experimentation, almost predictable. This process of discoloration became part of her visual language, representing the passage of time and the ephemeral nature of the world and human relationships. Thus one of her signature techniques was developed. She places objects of personal significance (a baby’s dress, a scarf, a curtain, domestic objects such as lace tablecloths or kitchen utensils) onto sheets of paper on the ground to create delicate trace patterns of the sun’s movement, in subtle shades of gold, yellow and warm browns. In some works sharper images are created by the positioning of cut stencils referencing traditional paper-cutting. Some include tiny, spidery drawings in black ink, revealing her original training in the Chinese traditions of ink-painting.

Carol Lee Mei-kuen, ‘Dinner II’, 2008, Time and Light on Newsprint, 79.5 cm x 110 cm

Image reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Essentially photograms made without chemicals, these ‘time-paper works’ are reliant upon natural forces, and by their very nature carry within them a meaning of transience, loss, and the impermanence of all things. The works are at once deeply personal, exploring relationships and the absence or death of loved ones, and also absolutely universal. In a 2008 catalogue essay Koon Yee Wang identified transience as a common theme in Lee’s work, “a paradoxical geography suggestive of exile and recluse.“

In my own conversation with Lee, she explained that a series of events in her personal life, including the sudden tragic death of her mentor and teacher, the illness and death of her mother, and the absence of her son, away at school in England, had prompted her retreat to her apartment in the hills above the Hong Kong hustle and bustle, focusing her attention on developing a significant body of work using this idiosyncratic technique. Traces of the movement of birds and insects, fallen leaves, and even tiny pitted marks caused by sudden showers of rain, can be detected on these works, many of them created on the tiled floor of her rooftop garden. They are characterised by a domestic, reflective focus on the trajectory of a life lived in relation to other people – as a daughter, wife and mother. Beautiful, quiet and profound, these simple images create a language of love and the inevitability of loss. “The uncertainties in life have become the source and core of my work”, Lee says.

Carol Lee Mei-kuen, “Little Lace Frock I”, 2009, Time and Light on Newsprint, 110cm x 79.5cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist

Carol Lee Mei-kuen in her rooftop garden, Hong Kong, photograph Luise Guest, reproduced with the permission of the artist.

Works from her ‘Threads of Luminosity’ series such as ‘Handkerchief 2’ and ‘Little Lace Frock I’ are reminiscent of the photograms of Anne Ferran, similarly imbued with the resonant meaning and significance of objects, in this case her mother’s handkerchief, and the kind of lace dress she longed for as a small child wearing hand-me-downs. A multi-panelled work such as ‘Close to Dusk’ is almost unbearably poignant, with its two empty chairs on the terrace signifying the shrinking of the family and the passage of time, as parents age and children move into their own worlds. Her material practice, using light and time on the cheapest possible newsprint paper, is in itself suggestive of the ephemeral nature of our constructed reality.

Carol Lee Mei-kuen, “Close to Dusk 16.30pm 28_12_2008”, 2008, Time and Light on Newsprint, 210cm x 240 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist

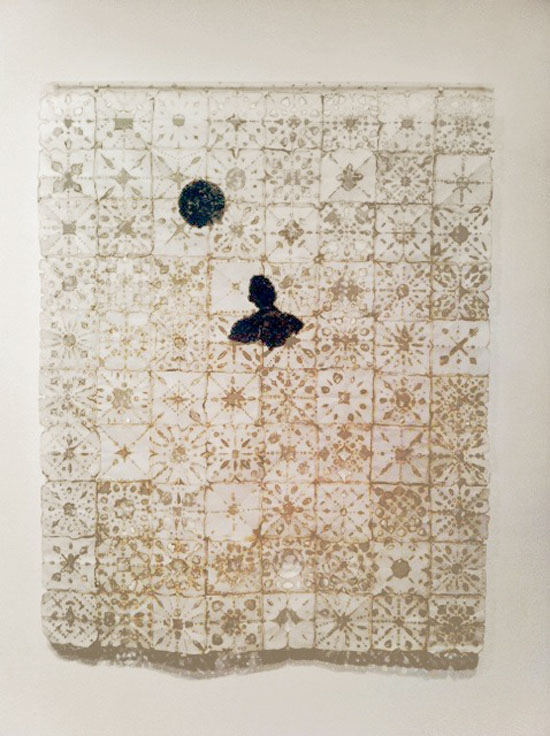

More recently Lee has returned to her earlier practice of burning holes into paper. She is currently showing with a group of artists, including Lindy Lee, at 10 Chancery Lane in Hong Kong in ‘Forces’, an exhibition exploring the idea of the five Chinese elements of wood, fire, earth, metal and water. Lee sees the burnt paper works as another way of dealing with the passage of time and the relationships between human beings and their environments. It is similarly difficult for the artist to control – at once predictable and unpredictable in its ability to create beautiful marks on the paper, or to destroy it.

Carol Lee Mei-kuen, “Burning 7”, 2011, Burnt Paper on Canvas, 66cm x 80 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist and 10 Chancery Lane Gallery

Lee uses burning as a drawing tool to create line, mark and colour in works such as ‘Burning 7’, which despite the gallery’s description is not physically attached to the canvas. Rather it is floating on the air, moving in the slightest current. Lee burnt each small square of paper separately and then joined them to create the larger work. The black figures are made of paper burnt to dust and glued to the surface, symbolising our transient presence in the world.

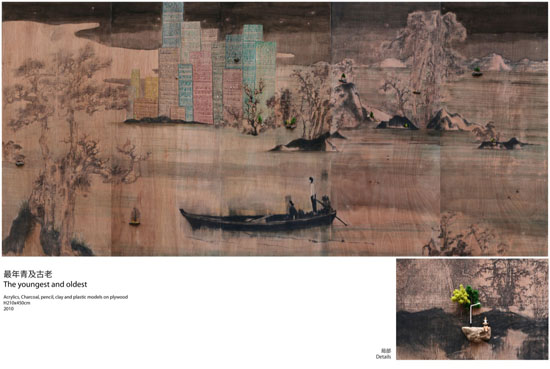

The practice of Lam Tung-pang may seem at first glimpse more outward looking and less focused on personal aspects of identity. In our conversation one afternoon, however, in his Fo Tan studio on the 6th floor of one of the multi-storey factory buildings that make up this once vital hub of industrial production (gone now, of course, across the border) he reveals himself to be deeply reflective and thoughtful. In less than twenty years his official nationality has changed from British citizen, to British National Overseas citizen, to Chinese Special Administrative Region citizen, and finally to Chinese citizen. This sense of flux and transformation plays out in his work. He has developed a technique of painting directly onto large sheets of plywood, using images borrowed from eclectic sources including Tang, Yuen and Qing Dynasty paintings. These are often applied as stencilled images, working with acrylic paint and charcoal, which soaks into the plywood creating an intentional blurring, thus evoking a sense of unease and uncertainty. In many works Lam attaches tiny model houses and trees, like those from a boyhood model train set. As a boy he imagined himself into an alternative miniature world, a feeling he seeks to recreate with works such as ‘The Youngest and Oldest’. This injection of an ironic and playful sensibility, hinting at the lost pastimes of a distant pre-handover childhood, juxtaposes the industrial past of Hong Kong, a time when factories in buildings such as the one housing his studio manufactured cheap toys and plastic ephemera, with the sense of the sublime landscape found in the ink paintings of the literati.

Lam Tung-pang, “The Youngest and Oldest”, acrylic, charcoal, pencil, clay and plastic models on plywood, 2010, 210 x 450cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist

Lam Tung-pang in his studio, Fo Tan, Hong Kong, photograph Luise Guest, image reproduced with the permission of the artist

Bookshelves in his studio sag under the weight of art books, both Chinese and Western. Lam sees the tiny, immensely detailed background landscapes in the works of artists such as Giotto and Piero della Francesca as possessing a similar sensibility to the traditions of Chinese painting. In addition to the deeply embedded history of line drawing and ink painting in Chinese art, Lam identifies a range of influences on his practice: Hong Kong born New Ink Movement Master Lou Shoukun, Sigmar Polke, Michael Borremans and Sanyu, a Chinese painter who lived and worked in early 20th century Paris are artists who recur in our conversation. He acknowledges the inherent tension in these western and Chinese sources, however. Western painting is like “opening a window in order to look out”, he says, in contrast to Chinese painting which is “more like opening a space inside oneself to escape from the outside world”. While it is evident that the literati painters, those scholars who retreated from the world in contemplation of the sublime, have a strong presence in his practice, he is nevertheless driven to make works which reflect the current state of Hong Kong in its transient ‘floating’ existence prior to 2047, the date which marks fifty years after the ‘handover’ – a date which fills many Hong Kong residents with some degree of foreboding. Currently showing in Vision of Nature: Lost & Found in Asian Contemporary Art, at Hong Kong Arts Centre, Lam’s ‘Past Continuous Tense’ suggests an elegy for a fast disappearing natural world, using images of trees sourced from Chinese, Japanese and Korean depictions of the forest as a wild and mystical place. Lam says his work creates a panoramic woodland, “but in a destroyed way”. His works combine many distinct elements – image transfers from antique paintings, magazine cut-outs, stencilled text, plastic toy models, all taken out of their original contexts and ‘reconstituted’ in the alchemical processes of the studio to create a new hybrid world. His practice acknowledges the significance of ancient Chinese traditions of art and scholarship, whilst recognising the loss of the past and the uncertainty of the future.

Lam Tung-pang, “Past Continuous Tense”, (detail view) charcoal and image transfer on plywood, 2011, image reproduced courtesy of the artist

Like Carol Lee Mei-kuen and Lam Tung-pang, Wong Chung-yu layers a deep attachment to the traditions of Chinese art and culture with a commitment to the use of digital technologies and new media in a Chinese context. He is attempting to ‘modernise’ Chinese painting both in terms of technique and subject matter. With his degree in computer science he began to think about how he could integrate digital media into his painting practice, and created his first digital artwork in 2003. Since then he has been able to mix his knowledge of programming with more traditional Chinese ink painting techniques, in works such as ‘Spiritual Water’. In this work a landscape painting lies flat, like a traditional scroll, with a central blank area which is actually a screen with back projection. When the viewer touches the screen a web cam is activated and the work then digitally simulates the diffusion of ink marks made by traditional ink painters and calligraphers. Later works such as ‘The World’ (an audio and narrative work) and ‘Spiritual Water II’, in which a black ink waterfall splashes and tumbles in constant motion, use random animation techniques. In ‘The Memory of Stars’ an ink painting hangs on the wall and is juxtaposed with a screen on which a similar image is projected. This image, however, changes in subtle and continuous ways, and requires a computer running in real time.

In Wong’s solo show at Hanart TZ Hong Kong in 2011 his interactive works posed questions about the relationship between audiences and artworks. In ‘When Time Flows Away’, two screens are hung one above the other. On the top screen a traditional ink grinding stick is activated when an audience member takes a ladle of water and pours it into the vessel below the screen. A computer program designed to calculate the effect of ink infiltration then interacts with the water in real time. Virtual ink begins to flow downward into the second screen, ‘washing away’ images from the last 100 years of Chinese history, including the Japanese occupation, Mao Zedong, Cultural Revolution propaganda, Deng Xiaoping and images of the 1997 handover. The ink grinding represents China and the ebb and flow of its history, and the work involves the audience in its alteration. Wong believes that ink painting expresses the deepest beliefs and philosophies of the Chinese people: “What I am interested in is how to reinterpret Chinese traditional art in a new way,” he says.

Wong Chung-yu, ‘When Time Flows Away’, 2011, water, digital projections and web cam operating in real time

Much contemporary Chinese art practice is underpinned by traditional skills, both of the western academic tradition and of techniques such as ink painting – calligraphy has always been the mark of the scholar in China. Current discourse about the significance of ink-painting in contemporary art practices explores this theme. Keith Wallace writes in ‘Yishu’, “A growing number of exhibitions [feature] artists who… explore and even push the parameters of what ink-painting should represent…a concerted effort by historians, curators, and critics not to let ink-painting slip into the abyss of historical dinosaurs, but to encourage ways in which its practice can continue to contribute to contemporary art”

I met the youngest of the four artists, Hanison (Hok-shing) Lau, in a café in a Mong Kok shopping mall, a curiously appropriate setting for an artist interview in Hong Kong. Meditative and quiet, his works employ found objects and ‘poor’ materials (in the sense of art povera) in sensitive and unexpected ways: cardboard packing boxes are glued together and carved to form mountains reminiscent of classical Chinese paintings, and paper towels are designed to form lakes and waves. He references traditional Chinese culture and poetry from the Song Dynasty, believing that young Chinese need to reconnect with their traditions. He wants people to take the time to really look at the world around them and the objects they are using. In a busy city where people buy a new cell phone, then throw it away and buy a new one in order to have the newest, most desirable consumer goods, Lau wants his audience to think more carefully about tradition and about the meanings inherent in objects.

Many of his works have a sly humour – ‘Letter to Marco Polo‘ includes a pair of boots made of teabags sewn together. They resemble the leather armour worn by the Entombed Warriors, referencing Marco Polo’s infamous neglect of any mention of tea in his accounts of his travels, causing some to doubt his veracity and conclude that his tales were fabricated fantasies. The ‘Table Top Gardens‘ series are miniature traditional gardens like those of the Ming Dynasty, with tiny carved cardboard mountains, and real plants and fish, which he ‘adopted’ out to a dozen people, including his mother, a traditional landscape painter. The ‘adopters’ were required to look after their garden and take a photograph of it every day. These photographs and the experiences and accounts of the garden ‘adopters’ were then exhibited with the works.

Hanison (Hok-shing) Lau, “Table top Garden”, 2008, Mixed Media including recycled wood, water, plant, metal and found objects, size not specified, image reproduced courtesy of the artist

Typical of the whimsical nature of his practice is ‘Century Old Shop’, a cardboard person-sized replica of a traditional Hong Kong shop (the kind which is fast disappearing, replaced by glitzy shopping malls). Inside his cardboard shop the artist walked around the city engaging people in conversation and exchanging or trading items with them. He found that old people particularly liked newspaper, because they can sell it, so he collected lots of that and gave it away for whatever the ‘customers’ offered to give him in return. The goods he received included used Starbucks coffee cups and assorted urban detritus, but also some money. The performance piece was documented and photographed, and the items he received, and the conversations he had with the audience participants then became part of the work. Perhaps this development of his practice from purely sculptural to performative comes in part from his experience as a performer in the Chinese opera, from the time he was a small child up until he left Hong Kong to study in Australia.

Hanison (Hok-shing) Lau, ‘A Century Old Shop’, 2010, old cardboard and abandoned materials, size not specified, image reproduced courtesy of the artist

I was reminded of Hossein Valamenash and the simplicity of his materials, which are employed so cleverly to create a complex set of meanings. Some of Lau’s deliberate choices of ‘poor’, recycled, non-art materials are reminiscent also of New York artist Sarah Sze, and her magical room-sized kinetic installations of an almost Heath Robinson-esque character. There is certainly a debt owed (and acknowledged) to dada and Duchamp, but Lau is giving voice to ideas about the destruction of Hong Kong traditions; the dispossession of the poor and those least able to navigate the ruthlessness of the global economy; and the current focus on empty materialism at the expense of important considerations of Chinese (and, specifically, Hong Kong) culture and history. He says that he wants to bring viewers into a journey between the past and the future, and between real and imagined worlds.

Hanison (Hok-shing) Lau, ‘Floating Landscape’, 2011, branches, sponge, found materials, size not specified, image reproduced courtesy of the artist

In their different ways each of these four artists pose questions about identity and belonging, prompted by their specific experiences as citizens of a place in the world which is undergoing its own unique transformation, pushed and pulled between its colonial past, its present day global identity, and its Chinese future.

About the writer: Luise Guest is a Sydney based art teacher and blogger who has been writing about Chinese contemporary art since her trip to China early in 2011 on a NSW Premier’s research scholarship. Spending time in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong she met and interviewed more than 20 artists, curators, academics and art writers. She is now an obsessive Sinophile attempting to learn Mandarin and impatiently planning future trips to China. Her interests extend to the broader spectrum of contemporary art in the Asia Pacific region. Her blog: www.anartteacherinchina.blogspot.com