Curiosity drove The Art Life to the National Museum of Australia. How has it weathered the storm of the history wars? Did it survive the intense criticism of its so-called “black armband” view of Australian history and which led to Dawn Casey being “let go” in 2003? In short, have things changed on Acton Peninsula?

The ways in which any of our national cultural institutions use art to tell their stories, and how the history of art fares in the process, is a cultural narrative often as interesting as the contents of such institutions. The way their collections are presented to curious visitors like the Art Life is worthy of some forensic commentary…

Inauspicious is the best we can say about our approach to the NMA. This must be the most exhausted example of fin-de-siecle PoMo architecture in the southern hemisphere. The sign out front tells you how successful it’s been in pulling the tourists, but the peeling pathway (the designer sculpture which supposedly points to Uluru) has had to be modified to save tourists from hurting themselves.

The clunky concrete forms (on which you’re not allowed to skate, ride or board) have been filled in with even clunkier bits of steel. Clearly there’s been no artist involved in its execution, and therefore no Moral Rights at stake.

As you close in, you see how tired is the six year old fabric of the building and its surrounds. It’s visibly rusting, peeling, fading, rotting, and leaking before you ever get to see inside.

And when we looked over the wall at the Garden of Australian Dreams we saw its faded paint and stagnant pool surrounded by features which have been rendered “safe” by other OH&S concerns, thus neutralising its original, sophisticated in-jokes…

…such as the poor Italian alder trees planted at an angle, now struggling to straighten themselves. Or then there’s a forest of other leaning “trees”, poles painted blue, (get it?) outside the Backyard Café, and the new fences strategically installed to prevent the elderly slipping and suing. And yes, even the “water feature” makes it into the pantheon of designer jokes!

This expensive playground is another fertile field for architectural moral rights disputes of the future. No doubt it will prove to be a DIY superannuation scheme for the designers (Room 4.1.3, a.k.a. Richard Weller and Vladimir Sitta) when, in the not so distant future, the Dream fades even more and the whole lot needs to be refurbished.

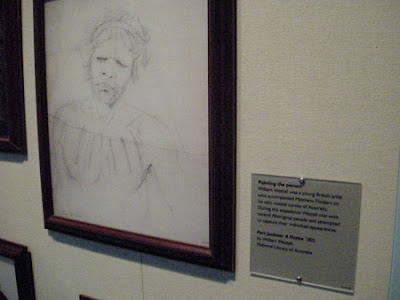

So we began at the beginning, walking up the stairs to a gallery titled Horizons: the peopling of Australia, which purports to tell the story of first contact, settlement and immigration. Around the first corner we find lots of images which look like Art. Dominant in this ensemble is a portrait of William Dampier, heavily wooden-framed, looking just like the real thing.

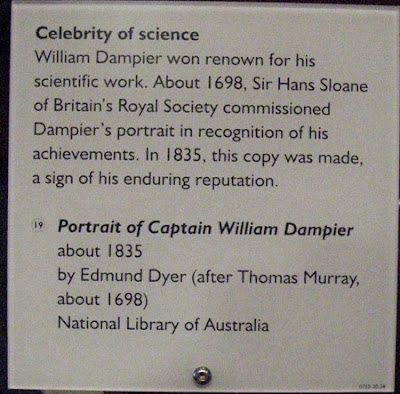

But alas we read the plaque on the frame that it’s a copy. The snazzy metal plaque tells us:

Captain William Dampier (the first Englishman to land in Australia) Copy of Portrait in the National Portrait Gallery. Presented by John Masefield (Poet Laureate).

So the original must be in the NPG in London, not the one across the Lake. But the NMA label at the front of the display tells us:

Mysterious. Apparently it’s a 19th century copy on loan from the NLA. But it’s located so far back in the diorama amongst the forest of plaques and display items, you couldn’t tell whether or not it’s a copy or not, so the authenticity effect works for most viewers. There’s another (admitted) replica beside it, an astrolabe, and on either side (yes!) there’s real bark paintings. One is by Wanungwamagula Nandjeewara (no date given) a Groote Island artist, and the other is by the great East Arnhem Land painter, Mathaman Marika (Rirratjingu language group, 1965). Phew! So there is real art here after all.

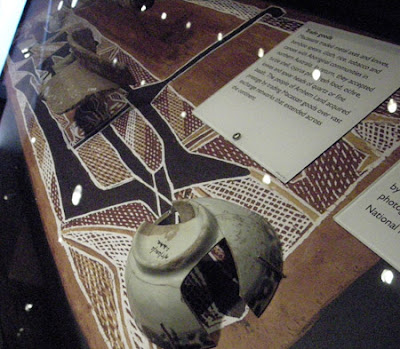

But wait! What’s this in front? Perhaps moral rights are not a problem for anyone at the NMA, for here is a life size replica of another bark painting from the NMA collection (0750.20.23), by “Mungurraway Yirrkala” (sic) also of 1965. But in this case it’s a very good facsimile (they credit the photographer), and the explanatory plaques are screwed straight into it, and little wire frames drilled into it which support (actual) fragments of Chinese export ceramics and other artefacts discovered in Arnhem Land from the time of the Macassan beche-de-mer trade. My goodness, we think, where do the values of authenticity lie hidden in such sophisticated curatorial subterfuges?

So we look to the labels. As you do. Asking, how should a National Museum account for the relation between authentic artefacts, and replicas? Ambiguously, as it turns out…

We move across the gallery towards the section which describes colonial settlement, past various archaeological artefacts, images of explorers, and illustrations derived from contemporaneous paintings, prints and other images, as well as some things not identified at all.

Here, with relief, we recognise some old favourites, images by the Port Jackson Painter, William Westall, Thomas Watling, and Robert Cleveley, all hung together and neatly framed with a nineteenth century ambience.

While the label suggests authenticity (quote: Port Jackson: a Native by William Westall, National Library of Australia), should they be framed like that without mattes, their paper squished up against the glass? No, but it doesn’t matter, because when you look really closely, you see that they’re only photographic reproductions. Does it say so on the label? No it doesn’t…

Alarmed, we ask ourselves, are there any works of art at all in this Museum? Well, we remember, there were those funny looking painting-like things hanging on that curvy ceilings on the way in – but they had no labels, no attribution, so we didn’t take them seriously. They are, we discovered later, “ceiling banners”, commissioned designs by four contemporary artists. We assumed (correctly its seems) they were décor, ambience building, suggesting the presence of art, without the risk of the real thing. Maybe they were sound baffles, or maybe installed to distract from the appalling lighting fixtures…

So off we go looking for works of art. We find lots of historical artefacts, coins, medals, tools, stuffed animals, clothing, cars, and millions of labels, plinths, and display devices everywhere. Actually, we guessed there are about three or four display objects or images for every authentic artefact. But that’s about normal for an effective theatre of display in such institutions.

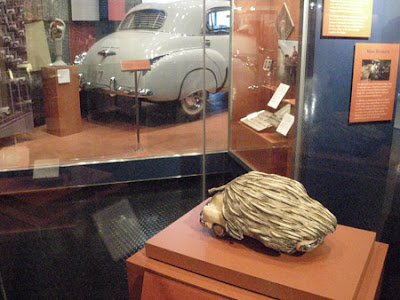

But we find no art, in the sense that a work of art usually connotes originality, authorship, authenticity, the idea of art in the mind of its originator. Except we do find a small ceramic sculpture by the Adelaide funk artist Margaret Dodd FJ Holden Pretending to be an Australian Native Porcupine (1982), on loan from the Art Gallery of South Australia, sitting on a plinth next to a real FJ Holden. A strange inversion of contextualisation to be sure.

Margaret Dodd, FJ Holden Pretending to be an Australian Native Porcupine, 1982.

Loan from the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Around the corner, illustrating the theme of suburbia, there’s a handkerchief-sized reproduction of a Howard Arkley painting of 1994 (courtesy of Tolarno Galleries). And a little further on there is an example of what appears to be folk art, a life-sized emu made of barbed wire, with a label: “Barbed Wire Emu. Made by Laurie Nilsen, cast aluminium, Barbed wire, and steel, National Museum of Australia”, but giving no time or place of production or other attribution.

But once we turn into the West Wing (the museum is a horseshoe shaped building) where we’ve entered the Gallery of the First Australians, we see artworks everywhere, from all historical periods, forms, materials and functions. Here we encounter a myriad of Indigenous objects, artefacts, and works of art from the earliest known examples, to the recent past. There’s a contemporary exhibition in the Focus Gallery “70% Urban: an exhibition exploring the growth of Urban Indigenous culture across Australia”, and a Gallery of Torres Strait and Islander art. Each example of indigenous artefact or work of art is surrounded, as before, with a multitude of exhibition devices, images, and interpretive texts, providing the contexts, origins, and indigenous identity of the artist. As we would expect of works of art in a national museum. And, while in this wing facsimiles are identified as such, other attributions are not as accurate as they might be.

As we walk back through the Museum, a powerful sense of ennui overwhelms us. How, we ask ourselves, are we expected to understand the rich examples of authentic Indigenous art forms when they are so profoundly decontextualised by the absence of other (actual) works of art in the rest of the Museum?

Perhaps, we speculate, this is a bizarre consequence of the unusual circumstances of the Museum’s creation, and the events which followed? The motivation for a national Museum was built, opportunistically, on a set of existing collections inherited by the Federal Government, brought together under one roof as a project to celebrate the Centenary of Federation. Unlike other State Museums, or the Powerhouse Museum, it was put together in a hurry, without the long histories of up to a century of collecting history of the other institutions.

In every other review or report on the nature of the NMA collection, the richness of the collections of Indigenous art, the core collection of which was once housed in the (then) Institute of Anatomy just up the road, plus the Aboriginal Arts Board collection, has been celebrated for its depth and distinctiveness. In a relatively short period of time in the 90s it was brought up to date by collecting urban Aboriginal art, some of which was produced in the Sydney Art Schools of the eighties. The overall museological context is, however, one of a discordant mix of historical artefacts, replicas, subterfuges, jokes, props, entertainment, too-clever architectural conceits and distracting design devices.

The effect is devastating for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous art. Without an appropriate cross-cultural context to demonstrate the care, consideration, interpretation, recognition and presentation of works of art, by which a national history might be told, the treasures of the Indigenous collection have been reduced to the status of historical artefacts. Just like the FJ Holdens, stuffed kangaroos, Victa lawnmowers, or worse, the ambiguously identified facsimiles, the implicit claim for all the Indigenous artefacts as “works of art” is thrown into question. Or, conversely, the status of all the Indigenous works of art is reduced to that of the historical artefact.

Thus the desired historical national narrative falls apart, not through a “black armband” account of history, but through an imaginative blindspot, a series of theatres of charade, resulting in a cultural incommensurabilty unwittingly constructed across the racial divide.

The Art Life is despondent. As our National Museum, we conclude that the place is an embarrassment. The presentation of its collections of artefacts, and the historical or national narrative it affirms, has lurched from controversy to farce through ideological correctness, through subsequent political interventions, to an complete absence of curatorial imagination and the resultant museological sleights of hand. Unfortunately, the loss is ours.