From Eve Sullivan…

LIFE IS A LAUGH, the poster says. So oddly quaint, in its restraint, spelled out in faded red block capital letters. Propped up at one end of the station platform amidst scaffolding and construction materials, a stack of old drums, an old caravan, a row of dim light bulbs and a giant panda head, this is all part of Brian Griffiths’ Platform for Art installation at Gloucester Road tube station. Not exactly funny Ha Ha, but more funny as in tragic, sad, like some kind of memorial to an old fairground, that never quite got built. The workers left, the backer pulled out, the people moved on to something else, unless of course you’re passing through the station. Somehow you can’t escape the feeling that someone still lives there, some creepy extras still lurking in the shadows (like the guy in the clown suit doing the runner in time-traveling DI Alex Drake’s recurring nightmare in the BBC’s latest Ashes to Ashes). Likewise, I agree with the comment posted on the Transport for London website: “The giant panda head is the scariest thing I’ve ever seen … please stop this traumatisement.”

This is what the Brits do so well, this wry self-deprecatory humour, with a touch of nostalgia. Yep, I loved Dave Allen, The Two Ronnies, Monty Python, The Goodies. I still laugh out loud at re-runs of Fawlty Towers. Those jokes about Manuel and the German tourists – ‘Don’t mention the war!’ – were irony weren’t they? Things have moved on since then. Now that the UK is part of Europe, and the white, Anglo-type experience isn’t all of it, Manuel is more likely to be doing the talking. Unless he’s turned into Mr Bean of course. And, in this era of rampant globalisation, even a smattering of European languages won’t make a dint in it. One way or another we’re all in a strange land, and ever-so-conveniently (if you’re a creative that is) lost in translation.

This, in a nutshell, is what’s behind Laughing in a Foreign Language at the Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre. Curated by the in-house Japanese Curator, Mami Kataoka, with a little help from Director Ralph Rugoff, humour is the new Esperanto enlisted to promote a common understanding. As we all know, playing gags, lifting jokes, being a tourist and just generally acting up for the camera are the stock-in-trade tricks of the contemporary artist, aimed at claiming our attention for more serious subjects.

The exhibition starts out with South-Korean artist Gimnongsok’s masquerade of a Mexican family paid to don animal suits to enact the fairytale of the Bremen Town Musicians. Chinese artist Jun Yang makes a step by step video instruction aimed at illegal Chinese immigrants trying to blend into Austrian society. The Iranian-born, Paris resident, Ghazel posts up offers of marriage to help asylum seekers obtain a passport. Barthélémy Toguo presents fake wooden suitcases, impossible to open, to get back at the customs officials. But, even putting aside the at times somewhat schoolbook geopolitics, there’s not really much to laugh about here. And, I’m not sure that the earnestness of the theme hasn’t entirely lost out on that old staple – irony.

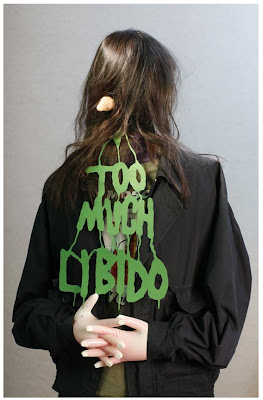

In the work of the thirty artists on show, there is a fairly predictable catalogue of themes. There are several sitings of clowns (by Rondinone and Rosefeldt) and various dress-up contingents (as in Marcus Coates’s shaman from Siberia), Australia’s own Matthew Griffin’s Rocker wearing prosthetic, ectoplasmic graffiti and Kutlug Ataman cross-dressing belly dancer (awful indeed). Co-opting others is a major theme. Olaf Breuning shows us the funny, chummy tapes of the guy on the road making friends in Japan, Ghana, Switzerland and PNG, reinforcing the fact that everyone is obliged go along with the western tourist. But like the Finnish artist Roi Varra’s idea of making the most of living in or travelling to exotic locations, the Artist’s Dilemma does seem at times rather spurious: man standing in a dinner suit on the ice, in front of a signpost featuring the choice between Art and Life. And it’s hard to imagine how anyone would agree to participate in his Wet-paint Handshakes.

The light touch rules here, and sometimes it works, as in Taiyo Kimura’s video clips, one of a guy brushing the teeth of a fish inserted in his mouth, and in another balancing chop sticks on his eyes – all played on a monitor hidden in a laundry basket. Or take the videos of Polish collective Azorro, whose We Like it A Lot one-line statement fits all occasions, as the ultimate art world Yes men , and who in Portrait of a Curator line up various camera shots to get curators, art critics and gallerists unwittingly posing with them in the background.

Monkey do, monkey don’t. Now it’s the curators who want to get in on the act with the Martian Museum of Terrestrial Art at the Barbican Art Gallery. Conceived from the point of view of the extraterrestrials trying to make sense of contemporary art, this exhibition takes an anthropological approach. The package includes an audio guide, as introduction to the various themes and foundation myths, a Martian alphabet decoder to understand the script, and a novelist (Tom McCarthy) employed to write the catalogue. Not to mention the usual army of writers, researchers, performers and soothsayers of various persuasions, joining in for the public events. Metal lines like circuitry diagrams connect the works up in a map of the universe-style expose of archetypal themes and narratives.

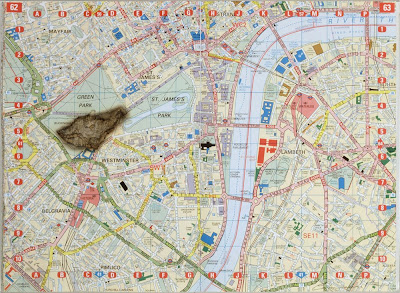

Starting out with the theme of Ancestor Worship Sherrie Levine is represented with her famous bronze-cast Fountain: 5, redoing Duchamp as pure sculpture, ‘a grand piece to them that is most definitely art’. Then there are various totems, including Thomas Hirschhorn’s giant cigarette lighter that, resembling one of those billboards in the round, is covered in reproductions by ‘the founding fathers’, Warhol, Mondrian et. al. Under Kinship, Marc Lombardi’s diagrams unveil the internecine relationships between governments and corporations. While Cornelia Parker, the great defender of Noam Chomsky in her current Whitechapel show, is here included (in the section on Spells and Charms) with her series of heated-up meteorites burnt through the pages of notable landmarks in that most instructive booklet, the London A–Z .

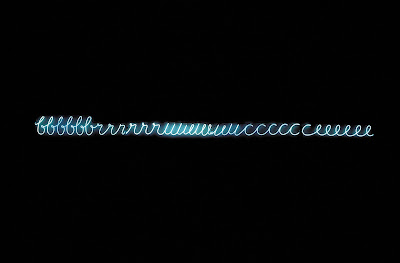

And if you’re into Holy Relics Jeffrey Vallance’s green Shag Carpet Relic from Elvis Presley’s Jungle Room, Graceland provided another entry into the mysterious reckonings of the great, the good and the trivial. Under the section on Making Contact Bruce Nauman’s My Name as Though It Were Written on the Surface of the Moon, shows how far you can go with neon. Other space ship themes thrown in for good measure, include a Ham Steinbach shelf with a bust of Star Wars’ R2D2, and Yves Klein’s Pneumatic Rocket hanging from the ceiling.

Exhausting and exhaustive, with its catalogue of themes, and a good deal of work displayed in museum-style vitrines, it’s hard to take in the work of so many artists (115 altogether) while also participating in this spaceship-earth business. Sure, there are lots of big names here. But why are they only interested in what happened between now and fifty years ago? And why so Eurocentric if it’s the whole planet we’re talking about? Where – you might ask – are the face painters and firewalkers? And why didn’t they pick up on some real human toys, guaranteed for art-like obsolescence, to ponder and make up their own mind about? Who is to say, indeed, which way is Art and which way Life. These Martians are clearly too in the know to provide much alternative.

It is with some relief then to go to the Institute of Contemporary Art where a more direct approach has been taken, employing the artist as a Double Agent. According to artist Phil Collins, nothing works better to catch your attention than a slap in the face. His portraits of curators Mark Sladen and Claire Bishop, among others, are taken the moment after their willing submission to this treatment (you can see this in their stunned, arresting expressions, and one-sided pink cheeks). In these and other works involving collaboration, role-playing, and some serious delegation, the artist is also the director.

In one of many ongoing variations on a theme, Barbara Visser in her video Last Lecture employs an actor to play herself, relaying the script through headphones, while maintaining a visible presence in silhouette, and responding to the previously recorded footage involving a different actor and studio audience, and subtitles that don’t match up with what is being said. This is a great watch/read/listen for those like me who thrive on participating in three conversations at once. If you like the idea of giving others a go, to let them make a mess of it while taking not too much responsibility, and a significant proportion of the credit, then the ceramic displays by Pavel Althamer and the Nowolipie Group , an organization for adults with disabilities, provides another case in point. Here, clay biplanes are the go and Althamer tries to make it like it really got off the ground in a plane that looks like an old aluminium saucepan. More provocative, but with nothing left to show for it but the video by Artur Zmijewski of the work as it goes up in flames and gets stomped on, is the workshop between Polish Catholics, Jews, Socialists and Nationalists played out on camera, in another example of this seriously oddball, relational practice.

And finally, I can’t go without mentioning the origin of all this chicanery in the work of Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabia at Tate Modern. If, like me, you don’t mind admitting to a certain degree of frustration surrounding the obfuscation, the reverential awe accompanying each annotated versions of the notes to … that surrounds Duchamp’s oeuvre, this exhibition is nothing short of a revelation for its direct approach, its blow-by-blow account of how it all happened as a communication between friends. When the rest of the world just did formalist, these guys were out on their own, copying, egging each other on. Yes, the sex jokes, human=machine, the woman behind the glass and the keyhole, Mona Lisa LHOOQ (everyone did a version), not to mention those late nude paintings (Picabia). Then there are the experiments with optics and cervical, rotational, devices, along with the rayographic advances in photography (Man Ray). And not wanting to be pigeonholed, as just painters or photographers or potentially sullied by the association with such platforms altogether (Duchamp), and working through the various manifestations of the landmark invention of the readymade, and the various position on in-jokes and chess games…