On her first trip to the Venice Biennale, Rebecca Gallo finds that not all art is created equal, even in the arena of the best of the best…

Venice is a fairytale town, impossibly beautiful and idyllically decaying. The streets are convoluted and full of dead ends, some of them into the water, which is slow and fetid in summer. Gondoliers are overpriced and oversupplied, and the vaporetto – the Venetian answer to public transport – is crammed and sprouts more smartphones, go-pros and SLR cameras than you can poke a selfie stick at. How was this place even constructed, with its ancient buildings thrusting down into the inky water, endless decorative window frames and rusting, woven metal grilles?

Venice, 2017. Photos by Rebecca Gallo.

For years now experts have been assuring us that Venice is sinking. While the blithely celebratory 57th Biennale group show, Vive Arte Viva, ignores the theme of imminent disaster or impending doom, many exhibitions around town were imbued with a sense of foreboding. From the disorienting, stage-set labyrinth of Fondazione Prada’s The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied., to Damien Hirst’s obscene monuments for an imagined ancient culture in Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, there was a sense of disaster and discovery. These themes were present in the works themselves, and also in my experience of them: some were pleasing discoveries, while others were total disasters.

Mussolini-era architecture in the Giardini. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

This was my first time at the La Biennale di Venezia, the oldest and most prestigious biennale in an art world that has taken this term and made it ubiquitous. Except that most biennales have quite a different format to Venice. The notion of national pavilions speaks to the nationalistic tendencies of fin de siècle Europe, when La Biennale started.

This approach feels particularly dated in an age of globalisation, where the contemporary art world has developed its own insular, universal language of materials and media. But the formula remains. With its antiquated, World’s Fair-style national pavilions, Venice is often described as the art world’s Olympic Games: countries send an artist, or a small group exhibition, to ‘represent’ their nation.

On my first visit to the Giardini, the French-style gardens where the permanent national pavilions are located, I was surprised by their strange and diverse architecture. Germany was large and imposing with its severe Third Reich neoclassicism and Canada had been mostly dismantled, planks of wood piled in the centre to form a fountain that periodically, and without warning, shot into a powerful jet. Spain was a full-brick affair, Australia a recently commissioned black box, while several countries were included in long wings that bounded the Giardini. These Mussolini-era white rendered facades were capped with bold, sculptural letters spelling out the countries’ names – in the case of ‘JUGOSLAVIA’ (now the Serbian pavilion), an awkward reminder that the borders and names of countries are less stable than the architecture built to represent them.

Exterior of the Australian Pavilion with video by Tracey Moffatt. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

With its cinematic photographs and politically motivated video collages, Tracey Moffatt’s My Horizon in the Australian pavilion felt timely. She drew parallels between the violence of colonisation and the mistreatment of refugees, hinting at the hypocrisy of a nation founded on colonising boat people subsequently vilifying asylum seekers arriving the same way. The most subtle and beautiful of her works was a video of Sydney Harbour, looking out through the heads, purportedly filmed by Gadigal people just prior to the First Fleet’s arrival. Through the construction of this impossible document, Moffatt seemed to be reminding us that it is not only the victors who write history – it is those with the inclination to record it. Through this retrospective documentation, Moffatt reiterated the voice and presence of the world’s oldest living culture, and captured a sense of peace before boats appeared on the horizon.

Anne Imhof, Faust, German Pavilion. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

This year Germany’s Anne Imhof was awarded the Biennale’s highest honour, the Golden Lion, for her provocative and divisive piece Faust. A raised glass floor was installed throughout the pavilion, and while performers moved above and below this line, the audience remained above it. Imhof’s young, androgynous performers moved around the space interacting with one another, but – aside from some intense eye contact – not the audience. A man perched on a wall-mounted shelf of thick glass and steel slowly raised his shirt to reveal, snug in the waistband of white shorts, the tip of a black iPhone. Two performers embraced in a rolling wrestle, viewed from below the floor by another player, and from above by a crowd of smartphone-wielding onlookers. This floor has been a contested, political site before: in 1993, Hans Haacke shattered the pavilion’s Nazi-era marble floors and invited visitors to walk over the rubble. In Imhof’s Faust, the politics were more personal. I felt like a voyeur, waiting for something to happen on the set of a reality TV show and unable to look away.

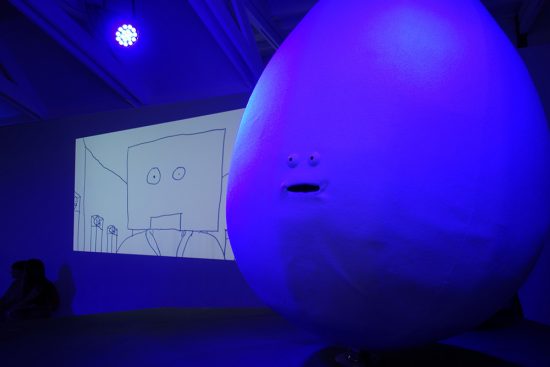

Erkka Nissinen and Nathaniel Mellors, The Aalto Natives, Finland Pavilion. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

The dark, close, sauna-temperature Finland pavilion was a highlight. Erkka Nissinen and Nathaniel Mellors took a playful but incisive dig at the outdated nationalism of the pavilion format with their video and sculptural collaboration, The Aalto Natives. Two sculptures – a very large, plush egg and a box with eyes – swayed about in the half-light, talking and casting videos on the walls from projectors strapped to their ‘heads’. A combination of simple animation and live action told the story of two messianic figures coming to terms with their irrelevance. It felt like the audience, in awkward, overheated close quarters, was complicit; that we were secretly enjoying this cave of absurdity amidst other pavilions’ earnest attempts for deep meaning and connection.

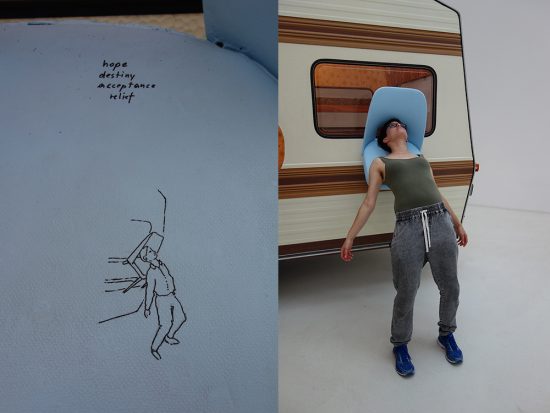

The author with Erwin Wurm’s ‘one minute sculptures’, Austrian Pavilion.

This sense of absurdity was echoed in another of my favourite works, Erwin Wurm’s one-minute sculptures in the Austrian pavilion. Everyday objects were slightly modified and simple instructions sketched on their surfaces. People crouched on suitcases, stuck arms and bottoms through holes in a caravan, stuck their heads under a lamp. Connecting through absurdity and folly felt like an appropriate antidote to the dire state of world politics.

Moataz Nasr, The Mountain, Egyptian Pavilion. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

Lisa Reihana, in Pursuit of Venus [infected], New Zealand Pavilion. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Senza Titolo (La fine del mondo) [Untitled (The end of the world)], Italian Pavilion. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

Having said that, there were highlights that were dark, serious and striking, in particular Moataz Nasr (Egypt), Lisa Reihana (New Zealand), and Giorgio Andreotta Calo (Italy). Nasr built a mud-brick facade inside the modernist Egyptian pavilion entryway; the space within was dark and the floor was earthy and covered in straw and the smell was strong and musty. A short film told the story of a young woman trying to lift her village out of a superstitious fear of the unknown. Reihana produced a scrolling tableau, a screen 23 metres long on which a story of colonial voyages, Pacific culture, trade and resistance slowly unfurls like a living, narrative painting. I almost completely missed the work of Giorgio Andreotta Calò, one of three artists representing Italy. A dark warehouse at the end of the Arsenale was filled with the legs of scaffolding. As I mounted stairs in the far corner, the building opened up. A pitched roof rose high above me, and I looked back down to see it recreated precisely, in mirror image, below: a reflection on still water. Called Untitled (The end of the world), Calò’s installation felt like a dramatised, poetic elegy to a watery end.

Alicia Kwade, WeltenLinie [One in a Time]. Installation view in Viva Arte Viva, Venice 2017. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

As well as the international pavilions, there is a unifying group show for each edition of La Biennale. Perhaps in an attempt to be democratic and inclusive, it seemed curator Christine Macel failed to sufficiently edit the list of participating artists. There were 120 participating artists, but it felt like much more. The exhibition spaces were massive, but still it felt crammed and few of the works were given sufficient breathing space. Much of the work was underwhelming, recalling the hit-and-miss over saturation of a university graduation show.

As if the national pavilions weren’t enough, the exhibition itself was separated into pavilions, with mind-numbing titles like ‘The Pavilion of Joys and Fears’, ‘The Pavilion of Colours’, and the most eye-rolling of them all, ‘The Pavilion of Shamans’. These pointless divisions served only to further confirm my suspicion that the curatorial premise was so broad as to be irrelevant, and so relentlessly positive as to render me oppositional and disengaged.

There were, however, some memorably excellent works amidst it all. WeltenLinie (One in a Time), an installation of metal, mirror and cast objects by Alicja Kwade, felt like a very sophisticated version of a funhouse mirror labyrinth. Sleek black steel frames stood impossibly on the polished concrete floor, and without close inspection it was impossible to tell which frames were empty and which held a spotless mirror. Single large objects (tree trunks, rocks) were placed on either side of the frames, an original and a cast. Walking around the piece I found myself doing double-takes, and testing how close I had to get before deciding if I was looking at a mirror or through into space beyond.

Nevin Alada?’s video work Traces saw playful musical interventions woven into everyday scenarios. Instruments were taken out into the world and ‘played’ by non-human forces and rhythms. The body of a violin was strapped to a merry-go-round, strings out. The bow was affixed to a pole so that it would run across the strings at each rotation. As the merry-go-round gradually slowed, each strike of the strings grew longer. One side of an accordion was strung to a street lamp, gravity pulling its bellows towards the earth with a tonal sigh.

The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied. Installation view at Fondazione Prada. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

Some of the most exciting and memorable art I saw was beyond the Biennale. The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied., a project curated by Udo Kittelmann and presented by Fondazione Prada, was disconcerting and totally absorbing. Works by artist Thomas Demand, stage and costume designer Anna Viebrock and filmmaker Alexander Kluge were seamlessly interwoven into an increasingly disorienting transformation of a grand old palace. Doors were everywhere: padded and upholstered, swinging saloon doors, doors that were slightly too small and that led around the back of sets. As the exhibition unfolded over several floors, it became increasingly difficult to tell what was ‘real’ and what was not: what was a second internal skin within the building – the set of the exhibition – and what was part of the building itself. Venice itself can feel like a film set at the best of times, making its backdrop to this exhibition even more pertinent and confounding.

The Boat is Leaking. The Captain Lied. was a completely constructed environment that gave a sense of peeking behind the curtain, but the real trick was that this version of ‘real’ or insider access is also a complete construct. Artifice was created and revealed in a single stroke: one of Demand’s photographs was followed by the set it depicted. From a distance it looked like a ‘real’ room, but as I walked around it, I realised the plants were fake, the grime concocted, and diffuse ‘natural’ light was revealed as carefully staged. It was a theme park where every experience is carefully designed. Surfaces were artificially aged like a rustic theatre set, except that instead of viewing it from a distance, we were the players moving through it.

A far less sophisticated take on the tension between fiction and reality insinuated itself across two major palazzos for Hirst’s Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. Room after room of sculptures and artefacts was purportedly the wreckage of an ancient civilisation found at the bottom of the ocean. Gargantuan bronze sculptures of imagined deities, complete with fake coral and barnacles, filled the rooms. At worst, it felt like an inexcusable waste of resources. At best, it could be another of Hirst’s explorations of the utter absurdity of the art market. To invest art with monetary value is to suspend disbelief, to give artists the benefit of the doubt. Here, Hirst proposes a situation – the discovery of lost artefacts – and tries as hard as he can to undermine this proposition with grotesque fakeries, whilst creating objects that, apparently, extremely wealthy people are queuing to acquire. I am mainly glad that I didn’t buy a ticket, but was given one by a friend who, after seeing half the show, could not bring themselves to enter the second venue.

Intuition, installation view at Palazzo Fortuny. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

Koen van den Broek, Cut Away #16. Installation view at Palazzo Fortuny. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

On my last day I visited Palazzo Fortuny, a gothic palace and one of the eleven Civic Museums of Venice. A vast exhibition titled Intuition unfolded from the basement of this former home and atelier of fashion designer Mariano Fortuny (1871-1949). Curated by Axel Vervoordt and Daniela Ferretti, it was the sixth and last in a series of exhibitions staged at this location since 2007. In a darkened room, a huge Basquiat painting faced off with ancient sandstone sculptures from 3000-4000 BC. In the lower courtyard, a curtain of visible condensation was thrown out into the light for Ann Veronica Janssens’ Volute, while water lapped at a stone step at the end of the corridor. A mezzanine floor held a collection of Marina Abramovi?’s interactive crystal sculptures, Standing Structure for Human Use (2017). One floor up, the sumptuous, dimly lit surrounds of the Palazzo were sensitively filled with drawing, painting and sculpture, from a scrawled Giacommetti study – dense graphite still shiny on the paper – to a cascading metal curtain by El Anatsui that divided the space with its jagged drapery. The lights, I noticed, were waxing and waning, apparently ‘vibrating’ whenever lightning struck in Italy.

Left: St. Anne and the Virgin Mary, 1500 circa. Right: Anish Kapoor, White Dark VIII, 2000. Installation view at Palazzo Fortuny. Photo by Rebecca Gallo.

The exhibition unfolded with textured paintings on crumbling walls; ancient, medieval and contemporary works speaking and sparking; drawing with ink in the rain; an invitation to roll clay into a perfect ball and add it to an immense table; an ancient cosmographical map carved into limestone installed directly below an identically-shaped composition of nails hammered into canvas and wood. Different ways of counting, mapping and marking time. Back on the basement level, a 1500s Madonna niche statue was installed adjacent to a white-on-white Anish Kapoor wall sculpture: meditation, spirituality and transcendence across time.

I had expected all the art at the Biennale to be totally astounding. If this was the Olympics, we were seeing the best of the best, right? Obviously this was an unrealistic expectation, but in retrospect, I am left less with the disappointment of terrible work (mostly it fades from memory, except for some exceptionally bad moments), and left with the stuff that moved me. The work that shifted things in my brain, even momentarily, reminding me that the ground I am standing on is not static.

La Biennale di Venezia continues to 26 November 2017.