In Yamaguchi Akira‘s drawing, the present has almost reached its crisis point writes Andrew Frost.

Is it just a coincidence that the Japanese artist Yamaguchi Akira shares his first name with the 1988 anime classic? Directed by Otomo Katushiro Akira is set in Neo Tokyo, a fantastic sci-fi city of the future built on the ruins of ‘Old Tokyo’. Now outstripped by advances in animation, CGI and motion capture, Akira is still an amazing visual experience. Its key scenes depict the future of 2019 as a cross between a feudal city state of warring political factions and a gleaming metropolis of massive towers, highways, plazas, concourses – and pervasive mind control.

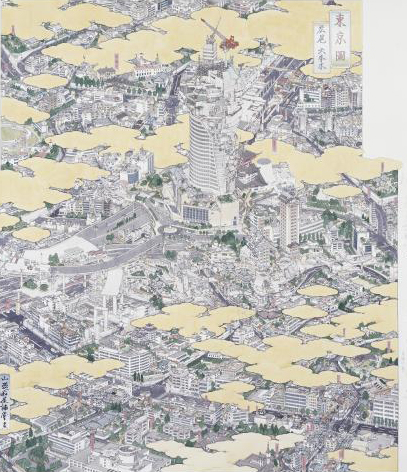

The coincidences between the name and content of a mostly forgotten movie and the work of a Biennale of Sydney artist grow even starker when you take a close look at his drawings. Yamaguchi’s intricate works depict a more-or-less contemporary city but the line between reality and fantasy is non-existent – the pen and ink drawings, highlighted with watercolours, are super detailed, intricate, eye-watering in detail and executed as if seen from above in that slightly angled perspective familiar from architectural drawings and vintage games such as Sim City. As you look across the drawings from right to left, the artist presents a movement through time: Tokei (Tokyo) Shiba Tower [2005] incorporates a screen at the right hand side of the installation that folds into framed sections – at right we see feudal workers, then as the city is built up from the foundations, the skeleton of Shiba Tower rises up, finally complete in the left hand frame.

The forms of Yamaguchi’s work refer to classical Japanese styles – Yamato-e [multipanel work] and Ukiyo-e [a style used in woodblock prints depicting historically significant scenes, the changing of the seasons, moments from classical literature] – but the content is contemporary. Tokei (Tokyo): Hiroo and Roppongi [2002] is a vision of the dense, hi-tech suburbs of Tokyo as seen through golden clouds, a subtle touch referring to the detailing of Japanese screen painting and plumes of toxic air pollution. Like artists of Takashi Murikami’s Super Flat scene, Yamaguchi incorporates modern technology and imagery into classical Japanese styles – the irony being both a commentary on the almost complete fusion between technology and Japanese society and the loss of those traditional values at the core of Japanese culture. Yamaguchi has been identified as being part of a younger generation of artists working in what’s been called “Neo-Nihonga” [or new Japanese style] which in fact refers back to the 17th and 18th centuries when a revisionist wave attempted to take Japanese art away from Western influences.

This strange push-pull between the contemporary world and the world-as-it-was is acute in Yamaguchi’s work, the form and style creating an odd friction with the content. The style of the pieces is all, yet the irony of the overlay creates its historical resonance. This theme recurs in Japanese art, especially within cinema, where the uncertainty of the present time [‘a precarious age’ if you like] is bedevilled by past wrongs. The recent cycle of Japanese horror cinema [The Ring, The Eye, Dark Water et al] all revolve around the present time making up for dark deeds of the past. In Akira the resolution to the crisis is yet another explosion that wipes the slate clean for the future. In Yamaguchi’s drawing, the present has almost reached its crisis point.

Roppongi is the home of the Roppongi Hills building featured in the work. The Mori Gallery founded by none other Biennale curator David Elliot is on the top floor. Roppongi subway station was the site most affected by the sarin gas attack in 1995.It also has a giant Loise Borgeois spider in the grounds of Roppongi Hills.

simcity is my all time favorite game, my dad even played that game *;.