Regular Art Life contributor and cultural commentator Carrie Miller has been invited to present a paper at the inaugural Not Fair. In this sneak preview of the talk she’s giving on Saturday August 7 at 2 pm, Miller threads a line of yarn between the work of Jake Walker, Grunge of the early ’90s and radical knitting…

One starting point for thinking about Jake Walker’s strange little paintings can be found in the short story Pay for the Printer by the sci-fi writer Phillip K. Dick (in The Preserving Machine, 1969). It’s a narrative some read as a left-wing critique of the failings of capitalism and of the culture of consumerism and mass production bound up with it. It’s set in a future where organic machines known as Biltongs produce copies or prints of all things that were originally man-made (knives, cars, cigarette lighters, music, everything). In the story these machines are dying and the copies they produce – imperfect prints, not of originals, but of prior copies – are breaking down. The humans are naturally freaked out that the world of simulacra on which they rely is self-destructing. In the end, people have to start building originals by hand as the machine-made duplicates turn to ash. Things are no longer printed by machines but made out of natural materials again – they are simple and crude, but they are “the real thing”.

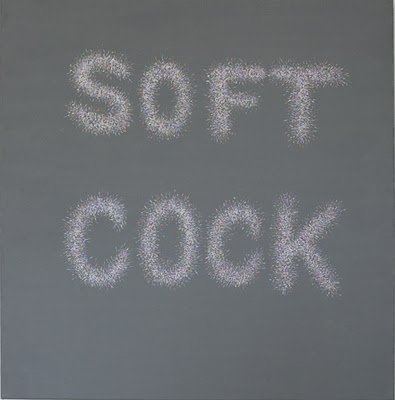

Acrylic on canvas, 65cmx63cm.

Courtesy of the artist

I think Jake Walker wouldn’t mind inhabiting a world of dead Biltongs. That’s because his work, while many things, is a response to the infinite reproducibility which characterises digital culture but more specifically, the rise in contemporary art of slick, highly resolved work which de-emphasises the hand-made – the mark of the artist – in favour of the globalised, homogenised, and easily commodified image.

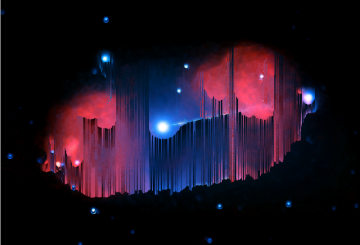

This stance on the state of contemporary art is literally embodied in Landscape Painting 2. Walker has literally defiled video art – graffitied it – asserting the painted surface, mark-making, over a computerised image.

For those of you who’ve read Jean Baudrillard, don’t think of Walker’s stance as just dumbly reactionary. His work couldn’t exist without the work it responds to – they’re co-extensive with one another – and he knows that.

Like his placing of text on ‘found’ paintings, Walker’s additions are not simple acts of vandalism but an attempt at rescuing and reviving something. He often takes the discarded and ephemera – a text message, a slang phrase, a self-help slogan, even a garage sale landscape – and isolates and preserves it, lending it a significance and permanence through the process of methodical mark-making.

The effect of this labour is paradoxical: the hi-tech, showroom-ready pieces that connect so readily to ‘the international dialogue’ that is contemporary art these days look infinitely reproducible and therefore disposable; on the other hand, Walker’s modest little paintings take on the auratic quality of a singular artifact.

Walker calls what he does ‘Folk Modernism’ and here’s his description of it: “Folk Modernism is more of an observation than a manifesto. It seems like there are a bunch of current artists using modernist aesthetics over post-modernist ideas. Art doesn’t need to be about the communication of ideas, we have the advertising industry, the media and the internet doing that job, visual art can’t compete. As a result, art has been increasingly prone to communicating ideas about itself – this is a closed circuit. It could go on forever but nobody outside the art world is the least bit interested.

“The conceptual set will argue that making art based on practice and aesthetic judgment can only result in decoration. Yet standing in front of a Diena Georgetti painting you are confronted with a cosmic power beyond the early 20th century abstract content. It’s as if somewhere in the process of applying acrylic paint to board the art gods got involved and turned the work into a pointer to another world.

“Aesthetically, society is in a crumby place. Most new buildings, cars, clothes, songs and websites are badly designed and constructed. It’s no wonder artists are looking back more and more, slowing down and reassessing things. Let’s move forward; let’s look back.”

For Walker, the “end-game of perfectionism” played by many of his contemporaries is “dry and soulless” – both as an artistic process and in terms of the cultural objects it produces. And if we believe Phillip K. Dick, it’s an end-game strategy that, pushed to its limit point, will implode on itself. This will be where artists like Jake Walker will come in handy.

Of course this is just one way of reading the end-game of late capitalism in relation to art: that there’s an irony inherent in the age of digital reproduction which is that the more reproducible images become, the more the original takes on the quality of ‘authenticity’, the more its ‘aura’ is amplified.

Now I want to try and situate Walker’s practice within a broader cultural movement or moment.

First, I think we can draw a line between what Walker likes to call ‘Folk Modernism’ and the ‘Grunge Art’ of the early 90s exemplified by Adam Cullen, Hany Armarnious, Mikala Dwyer, Nike Savvas and Destiny Deacon.

It was also a response to an earlier cultural moment – the slick conceptualism of 80s art and the over-produced, synthesized sounds of Stock, Aitken, Waterman. Suddenly, Kurt Cobain made Nanna’s hand-knitted cardigans and unplugging MTV cool and a DIY punk aesthetic and ethos took hold in a way not seen since the late 70s.

There was an overtly ‘hand-made’ quality to the work of Grunge artists. They were also interested in elevating the ephemeral. Works were attached to walls with masking tape or placed on the floor. There was a reification of ready-to-hand domestic materials in Grunge installations including biros, glad wrap, recycle bins, broken TV sets – even road kill.

But differently to Walker and his contemporaries, there was a nihilism to aspects of the Grunge movement which was cashed out in terms of hedonism and excess. Cullen, for example, painted to punk music, referenced Nirvana lyrics, drank like a bastard, and took the same drugs as Kurt.

I think a helpful analogy for understanding the similarities and differences that link these two points in Australian art history is in terms of the relationship between Hardcore Punk and the Straight Edge movement it spawned. Straight Edge is a subculture founded within Hardcore Punk in direct response to the hedonism and excess of it through the embracing of the ideology of abstinence (see Stuart Bailey’s work here which I think fits with the Folk Modern aesthetic and has explicitly dealt with the Straight Edge movement as subject matter)). In the same way, Folk Modernism, while remaining essentially Grunge in its aesthetic, rejects the nihilism of Grunge – getting things down “hard and fast” to cite Cullen’s catchphrase – in favour of a privileging of labour and technique.

It’s impossible to give a definitive list of who is part of what I’m calling Folk Modernism but I can tell you who Walker likes and whose practices he thinks he has an affinity with. They include: Timothy Price, John Spiteri, Rob McHaffie, Trevelyan Clay, Matt Hinkley, Fergus Binns, Mark Rodda, Sean Bailey, Nathan Gray, Dylan Martorelli, Kate Smith, Alex Vivian, Francis Upritchard, Vicky Browne, Rohan Wealleans, and Julian Hooper. I think it’s also fair to say that the work of practitioners around at the inception of Grunge such as Elizabeth Pulie is relevant because it has actually developed along the arc I’m tracing between Grunge and Folk Modernism.

There’s also a connecting movement between the two art historical moments I’ve been describing and that’s Street Art. It was also driven by a DIY, punk sensibility but elevated ephemeral graffiti to the status of a enduring art form through a more refined approach to the practice. It was in part a reaction to an overheated contemporary art market and the bloated prices people started paying for it.

Of course, now it’s possible to Google ‘How to Make Grunge Art in Photoshop’ and handy instructions will follow. And accidentally painting over a Banksy on the side of a building is considered a great cultural travesty. No doubt Folk Modernism will become appropriated in the in the same way. You can already make hand-made looking marks in graphic design programs, including your choice of brushstrokes and mediums.

So to recap, I think a line can be drawn from Grunge to Street Art to Folk Modernism both in terms of what they have in common – a DIY, hand-made, punk aesthetic and ethos – and what they reject in the movement or moment that came before them (I think the intersecting point of these three ‘movements’ can arguably be found in the work of Ricky Swallow).

Before I finish, I’d like one more roll of the dice. To bolster the speculation that Walker’s work is representative of something more general happening in visual culture I think we can situate it in terms of a ‘DIY’ subculture that’s emerged in recent times and is exemplified by, among other things, ‘guerilla knitting’ or ‘yarn bombing’ – a type of graffiti or street art that employs brightly coloured displays of knitted or crocheted material rather than spray paint. So let’s drop the ‘Folk Modernism’ tag here and take up the term that’s most often used to describe this new DIY, indie culture: ‘Hand-made’. It’s the subculture that’s been captured by the recent doco Handmade Nation and the Australian film Making it Handmade which premiered this week at the Melbourne Film Festival.

The artist, photographer, and filmmaker Faythe Levine first authored the book Handmade Nation: The Rise of DIY, Art, Craft and Design in 2008 (Princeton Architectural Press, 2008), and then made a film with the same name which charts this new subculture that “weds DIY and craft techniques with a punk aesthetic”. The movie documents a “movement of artists, crafters and designers that recognize a marriage between historical techniques, punk and DIY ethos while being influenced by traditional handiwork, modern aesthetics, politics, feminism and art” (Amazon.com).

In other words, the Hand-made movement contains all the elements of Grunge but with a reverence for historical and traditional techniques that was lacking in that nihilistic aesthetic. Precisely what separates out Walker’s Folk Modernism from Grunge art.

For those who like their punk old-school, this may all seem a bit ‘Soft Cock’, to cite one of Walker’s paintings. But like the Straight Edge movement’s claim that living sober is the most hardcore thing you can do, I think that going Folk Modern shows a type of moral courage in the face of the proposition that making art is increasingly futile in an image-saturated, digital culture.

This article is the basis for a talk to be given by Carrie Miller at Not Fair, 79 Stephenson St, Richmond, Melbourne, on Saturday August 7 at 2 pm.

Jake Walker won the inaugural Howard Arkley Award at Not Fair for best work.

Pingback: F*** Me Dead: Folk Modernism and the return of Grunge [or the arrival of post post modernity?!] « THE BROTHER TONGUE

plainly this is daubism which i began in adelaide in 1991 Google it.

i was taken to the federal court of australia for this art practice and now

imitators are winning prizes for it.

Pingback: The Art Life | researchlm