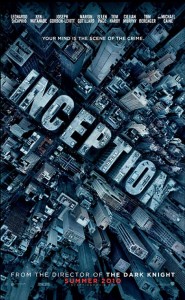

Ian Shadwell wonders whether Inception is great entertainment or an over-inflated pseudo-profound hodgepodge – or maybe both?

Inception is a film that should be welcomed. A Hollywood blockbuster, aimed at the mainstream, that deals with an elusive subject in a complex manner and delivers an ending that asks as many questions as it resolves. It is as far as you can get from the brittle sturm und drang of popcorn movies such as Transformers and still fill cinemas on tight-arse-Tuesdays.

And yet, for all of the claims made on its behalf, and despite the loftiness of its ambitions, it is an unsatisfying film, that falls victim to the narcissistic impulses that will always tug at big budget blockbuster sci fi. But before the whining, lets talk about why you should see it, because it is, without question, a film worth seeing.

In the first instance, Inception is a perfect vehicle for the kind of digital hi jinks that make for a compelling spectacle. Cities bend and stretch, gravity is suspended, time slows, the world is reinvented with the logic of dreams. This alone is worth the ticket price. Particularly, an extraordinary zero gravity sequence, which is seamlessly realised. Also of interest for the art junky is the hyper-Corbusian architecture, which structures some of these phantom cities. All this is brilliantly realised.

So too the performances, which are all concise, focused and as much as is possible, compelling in the midst of the wildly rolling action. Ellen Page fills her token female position with admirable depth, somewhere between confusion and panic, yet reciting her lines with the kind of gumption that keeps the action on the right side of coherency. Similarly, Leonardo De Caprio has managed to make the most of the confusion with a focused presence that is central to the parts of the film that do succeed.

Which brings us to the problems. There is uneasy tension between the need to explain the precepts of the action and then the breathless rush to exercise the possibilities they offer. This tension creates a film that treats the issues that lie at its heart, the “MacGuffin,” with too much muscularity. They become rhetorical and lose that elusive dream logic, the poetic truth, if you will, and instead are replaced by a schematic notion, which turns what should be surreal insight into a Wikipedia styled discussion of “reality”.

Whilst it may be an unfair comparison, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, achieves what Inception aspires to. It is a film that embraces the elusiveness of the dream and the unconscious and creates a world within which a great emotional truth is communicated. A truth so elusive, that it could only ever be understood by watching the film. Charlie Kaufmann understands the layered, constantly collapsing, irrational complexity of the unconscious in a way that escapes Nolan’s strictly structured thriller. Thus the truth at the heart of Inception is eventually turned into a bland summation of popular thinking on the “idea of the real”, an undergrad corollary of Descartes deceitful demon, alongside some Freudian sci-pop.

This shows in the characterisation, which for the most part is sacrificed on the altar of this “meaning”. The central relationship becomes nothing more than a discussion of this idea, with the depth of the characterisation shunted into the figures of two children, who stand for all that could be lost or gained from De Caprio’s “mission”. If, as Freud said, the unconscious is structured like a language, then this is nothing more than the thought bubble from a comic strip.

Yet, maybe such criticism is undeserved, for it is hugely entertaining. Perhaps the work could be better understood as a meditation on the power of cinema. After all, on each “level” of its tripartite construction various cinematic action tropes are reproduced, each held in thrall to the other in a complex and genuinely exciting thriller. Here, these cinematic elements do indeed have a dream-like veracity, the type of borrowing that the unconscious does. Villains are anonymous, expendable, automatons, whilst the hero always manages to survive impossible odds. With these kind of devices Nolan is able to elevate the action into that specific realm of “pure action”, hypnotising the audience with its apparent necessity, though one is not always sure what is at stake. Here then, it fulfills the traditional role of film, that of the shared dream, in which all those things missing from life are shown to us on the screen. Drama, action, a beginning and an end, albeit circular. The dream then, is nothing to do with the character’s unconscious, but ours, a stitched together montage of cinema itself, in which the whole becomes an hallucinogenic head-rush, a fever dream of the collective unconscious.

Or maybe its just a good night out.

There are also huge ideological flaws in the narrative itself, not just in the lack of surreality. Whilst Leonardo is the main protagonist of the film, the film does posit a lot of its time in the psychological landscape of a billionaire’s son. Sure there are ambiguities as to whose head you’re in at any given time, but ultimately they all point in one direction and resolve, a rich kid’s daddy issues. foul.

at best this films subtle political agenda will get in the head of a rich corporate head who feels empowered to deviate from the greed and self interest of their family’s empire. At worst those who can’t relate to being a neglected billionaire kid (99% of the population) are instead forced to assume the role of empathy for the rich and the powerful. It would seem, even capitalists have feelings….

The director says the same exact thing with his Batman flicks.