Luise Guest visits Go Figure: Contemporary Chinese Portraiture at the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation…

In introducing former Swiss diplomat, businessman and art collector extraordinaire Uli Sigg to the audience gathered to hear him in conversation with curator Claire Roberts and Caroline Baume at the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Gene Sherman uttered a great throw-away line: ‘Yasser Arafat has escaped twice today.’ She was of course referring to the life-like sculpture of an ancient, wizened and wheelchair-bound version of the Arab leader in his incarnation in ‘Old People’s Home’ by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu. Together with a selection of important works from Sigg’s vast collection of contemporary Chinese art this work is the main attraction at Sherman’s Paddington space, and it is interesting to see audiences interact – somewhat uneasily – with the dodgem-like antics of thirteen old men, once powerful leaders, slumped sideways and drooling or slumbering in their endlessly moving, rotating wheelchairs. It makes you think of authority rendered impotent with age. One woman standing in the middle of these geriatric dictators said to me, “Isn’t this wonderful!”, then, after a pause, “Actually, it’s really, really depressing.” Both statements are true. It is wonderful, in its hyper-real virtuosity, and its unveiled attack on authority and power. It is also a salutary reminder of the fleeting nature of such power, and indeed of youth.

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Old People’s Home, 2007, mixed media installation. Detail. Courtesy M+ Sigg Collection, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation and National Portrait Gallery.

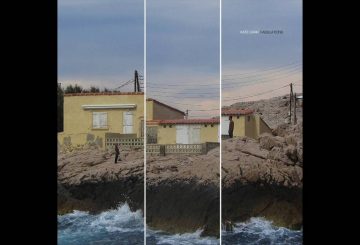

In a two-city exhibition (here, in Sydney at SCAF and in Canberra at the National Portrait Gallery) we are privileged to see fifty five works drawn from Sigg’s collection. Almost 1500 works from the collection will go to the new M+ Museum in Hong Kong, due to open in 2017. Curated by Dr Claire Roberts, the exhibition explores the notion of portraiture in an innovative and provocative way. At the entrance to the Sherman Foundation Gallery sits a pensive Uli Sigg, reading a newspaper. It’s another hyper-real sculpture by Ai Weiwei, a homage perhaps to Sigg’s position in the canon as someone who recognised the significance of what was happening in the artworld in post-Mao China, at a time when almost no-one else was taking any notice. He began his collection with the idea of deliberately putting together a document that recorded this extraordinary history. The exhibition includes a work by Shen Shaomin,( http://www.shenshaomin.com/) a collapsed portrait of Mao Zedong which appears to have slid off the wall and crumpled at our feet, as well as works by Zhou Tao and Wang Jianwei.

Shen Shaomin, Standard Portrait Mao Zedong, 2009, Courtesy M+ Sigg Collection, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation and National Portrait Gallery.

The works raise questions about Ai Weiwei’s deliberately provocative article published in the Guardian last week, coinciding with the opening of the ‘Art of Change: New Directions from China’ exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, in which he states bluntly that” the Chinese artworld does not exist” as it is not possible to make art where there is no genuine freedom of speech. No doubt Ai has his reasons for making a public statement this radical at this particular time, but it is also true to say that artists in China have always been able to create works with layers of complex meanings, which may be ‘read’ in many ways, and which have often been overtly or covertly critical of aspects of their own society, past and present.

When I met Wang Jianwei in his Beijing studio last year, the week prior to the opening of his major exhibition, ‘Yellow Signal’, at the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art, he spoke of the Buddhist underpinnings of his recent work, and how disheartened he is that western audiences remain so focused on the art of the 90s, the Political Pop and Cynical Realist painters. In our conversation he also spoke of Confucianism, Taoism, Lacan and the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek, spinning a web of ideas so complex that at one point I thought my translator may pass out. Much of his work is about the importance of doubt, and how Chinese history has to this point been ruled by the need for clarity and certainty. “If the green light is the history of art and the red light is science then contemporary art exists in the yellow light,” he said. This ‘yellow signal’ is the transitional space between the green light of freedom and the red light of control. Like so many Chinese artists, Wang Jianwei is adept at finding that liminal zone within which to operate.

Artists in China have responded to social and political changes in many and varied ways, but as the Sherman Foundation exhibition notes point out, “their work may be likened to a skin, a sensitive surface upon which the artist records ideas and questions, probing and complicating our understanding of the changing ‘face’ of China”.

Ai Weiwei, Newspaper Reader, Courtesy M+ Sigg Collection, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation and National Portrait Gallery.