Isobel Philip takes in The Big Picture at Stills and finds magic in the pulsating lights…

A group exhibition curated by Bronwyn Rennex and Josephine Skinner at Stills Gallery, The Big Picture confronts the pictorial plague of the digital age by interrogating the status and agency of the recorded image and questioning the way it mediates our experience of the world at large. Blinded by a surplus of visual stimulus, we often overlook what is right in front of us. Arresting the viewer’s gaze through playful acts of repetition and fragmentation, the photomedia, video and installation works on display in the gallery re-direct our attention to scenes that either pass by unnoticed or drown in overexposure. They teach us how to look.

Taking over an entire gallery wall, Penelope Umbrico’s ongoing project Suns from Sunsets from Flickr is a tessellating mural of photographic prints that appears at first glance as a vibrant — almost phosphorescent — latticed abstraction totally divorced from the real. And yet on closer inspection we realize that this grid is made up of small snapshots of the sunset, that faithful photographic cliché and the crown jewel of the picture postcard. Over-photographed, the setting sun is less a subject than a decorative motif. Umbrico knowingly exploits its ubiquity, creating an archive of repeated and interchangeable images sourced from the photo-sharing website Flickr. While each individual sun is a different colour and a different size (with some reduced to a pixelated haze), they collectively describe a single gesture and a shared photographic impulse.

But this collection of borrowed sunsets does more than just reveal staid pictorial conventions and the rampant compulsion to recreate images that already exist. It unearths a fragile temporality. All of these setting suns are on the edge of disappearance, about to dip below the horizon line. They linger in the ‘magic hour’. Yet however magical this moment may seem, it is a standardized interval of metric time that appears without fail every day (well, one would hope). The setting sun is a metronome. It keeps time.

Umbrico’s ever expanding grid of setting suns is a temporal index. It is a pictorial calendar and stock photography’s answer to On Kawara’s Today series.

Daniel Connell, Lightless, 2012, CRT TVs, multiple 4:3 videos, looped. Image courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery. Copyright of the artist

Daniel Connell’s video installation Lightless projects a similar metaphoric subtext. Looped footage of flickering lights appears on the CRT televisions scattered around the gallery’s mezzanine level. Filmed in underground car parks, tunnels, back alleys and lifeless interiors, these videos document the slow death of fading light bulbs. But the bulbs never really die. The videos loop, the lights continue to flicker. This is a pulse not a death knell.

These blinking lights follow their own rhythmic patterns and frequencies. As we walk amongst the jumbled arrangement of screens we move through a symphony of flashing light. We can almost hear the dissonant rhythms of these pulsating bulbs. It is noise written in light, a prolonged swansong caught on repeat. These looped intervals – hesitating on the edge between on and off, much like the setting sun — are the constituent parts of a temporal collage. Like Umbrico’s photographic mosaic, Connell’s installation constructs an image of time (the protracted moment, the interval) in spite of its immateriality.

The same idea animates Drew Flaherty’s video work, Loading Cycle. Flaherty uses the configuration and incessant spinning of the computer loading icon to re-enact the lunar cycle. The waxing and waning of the moon is synchronized with the mechanisms of the digital world. This deceptively simple visual pun conflates a digital time-keeper (though perhaps time waster is the more accurate description) with a natural one. In this way it participates in the ‘taxonomy of the temporal’ that unravels in the work of both Umbrico and Connell.

Tim Webster, Flow, 2012, Digital video, duration: 8:04 minute loop. Image courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery. Copyright of the artist.

Tim Webster’s Flow, a video projection made of vertically composited footage of rushing waterfalls, provides the (silent) accompaniment to Connell’s symphony of flickering lights. These slithers of running water resist perspectival reasoning. Each segmented waterfall moves in a different direction and with a different intensity. This is a fragmented and discordant panorama where the flight paths of the birds that pass in front of the falling water are reduced to a sequence of jump cuts. There is no horizon to orient the viewer, just the hard edges of collision and the competing force of abutting cascades.

The slight schism between the speed and intensity of each waterfall fragment produces a mess of aberrant yet synchronized rhythms. Again, there is a silent symphony. The surging crash of the water vibrates out of the projection. In this work, as with Connell’s installation, we find the sonic buried in the visual.

This is another image of immateriality, another instance of the invisible made visible. We discover the same impulse — the same drive to visualize the immaterial — in Gemma Messih’s sculptural installations. She plays with the limits of the photographic image through rupture and superimposition. In I’ve only just realized how important you are (to me) a photograph of a mountain is propped up against a pile of rocks. The two layered objects — the photograph and the miniature man-made mountain — share a mimetic bond. Each echoes the form of the other in a quiet pantomime of Baudrillardian simulacra.

A different logic permeates Messih’s other work. In Untitled (way out) and Someone else’s horizon the photographed landscape has been punctured, in the first instance by a rock (that now lies dormant on the gallery floor) and in the second by the artist herself. Here, the image becomes a threshold — a screen to be passed through. What we are left with is the trace of a performance and the memory of a gesture. We look on as absence enters into the (big) picture.

Patrick Pound, Portrait of the Wind (detail), 2012, Giclee print on rag paper, 127 x 230 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Stills Gallery. Copyright of the artist

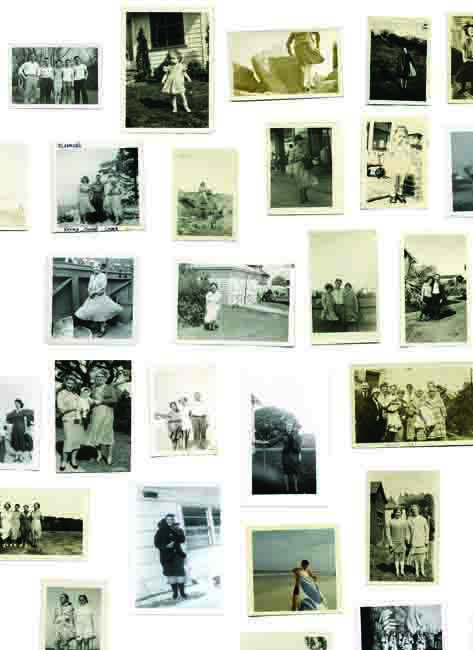

It is in Patrick Pound’s work that this line of thought reaches its apotheosis. His thematic arrangements of found photographs play out the poetics of absence. In Same place different people a row of photographs with the same background are arranged in a line. Each image frames a person mid-conversation as they occupy the same seat as their neighbour in the adjacent image. This row of photographs is disquieting. The backgrounds are the same but there are subtle compositional discrepancies in each. I found myself looking past the figure and into the edge of the image, trying to detect the differences. The figures become transparent, an absent presence that the viewer looks through.

In Pound’s Picture of the wind the pull of the absent and the immaterial is stronger still. Again, the figures in the photographs dissolve. Pound is not interested in these people, but in the space that surrounds them. He has composed an elegy to the wind that once rustled their skirts and ties and tussled their hair. Caught in the act, the wind inhabits a temporal threshold like that of the setting sun or the flickering light bulb. We see it briefly, on the edge of its disappearance, as it caresses and envelops these anonymous figures. They frame and mediate this composite portrait of an invisible force. Through them, we see the wind as form: as trace and imprint.

As the wind commands the gaze, the intangible and invisible takes centre stage. And with one fell swoop the exhibition asserts its thesis. For in the midst of a world overflowing with visual stimulus, an image still has the power to show us something we didn’t realize we could see.