Luise Guest meets Wenmin Li and discusses perspectives, painting and Hockney…

David Hockney made a short film with Philip Haas, A Day on the Grand Canal with the Emperor of China, which documents a 17th century scroll painting, ‘The Kangxi Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour’ (1691-1698) by Wang Hui. In a televised lecture about the documentary he says that he came to love and appreciate oriental art through his investigations into the possibilities of photography. As one might expect from the creator of images of Mulholland Drive and LA canyons that use multiple viewpoints to explore the nature of seeing, Hockney is fascinated with how Chinese painters represented distance, space and movement without Western-style fixed-point perspective.

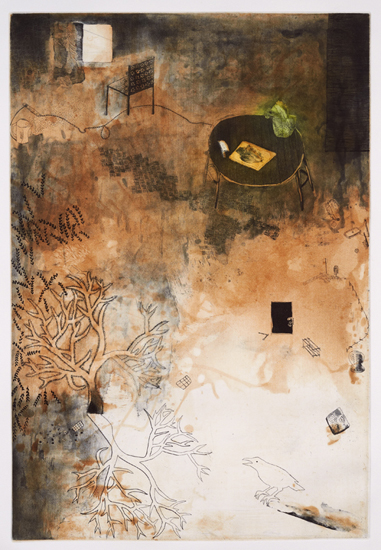

Wenmin Li ‘As It Goes By ‘ 73 x 50 cm, etching, 2009, image courtesy the artist

When I first saw drawings by Chinese-born Wenmin Li, initially in an exhibition in Hong Kong and then again here in Sydney, I immediately thought of Hockney. There are the multiple perspectives, the charmingly quirky observations of daily life and all its tiny details – clothes lines, chimney pots, window frames, potted plants, dogs and birds, chairs and shower curtains and kitchen cupboards – even the clippers she used to cut her father’s hair when he visited her from China. There, too, are the layers of pattern and mark and tone, reminiscent (to me, at least) of Hockney’s narrative etchings, such as ‘The Rake’s Progress’ series.

I met the artist, who is Deputy Director of the International Drawing Research Initiative (IDRI), at the College of Fine Arts, UNSW, on a Saturday afternoon in September. Surrounded by her works at Flinders Street Gallery, we had a long conversation about her practice, punctuated by traffic roaring towards Taylor Square, deliveries of wine for the next gallery opening, and a rather cross woman attempting to pick up a painting. I was intrigued to discover the story behind this artist – trained in the rigorous oil painting department of Luxun Academy of Fine Art, the oldest art academy in China, and now based in Sydney, having completed her postgraduate studies and PhD at COFA. Towards the end of our conversation, I asked her what art images she had pinned on the wall of her studio, and what artworks she returned to again and again in her life. She mentioned the two giant figures of Chinese brush painting, Ba Da and Qi Baishi, although she says “there are a lot of things I can’t read, can’t understand” in their works, never having studied traditional Chinese art. However, it is images of old master paintings that she surrounds herself with now. I think of Auden’s ‘Musee des Beaux Arts’ about Breugel’s Fall of Icarus, in which the tiny figure of the boy who flew too close to the sun falls unnoticed into the sea while the farmer continues to plough his field and life goes on. This emphasis on the beauty in the banal is what we see in Li’s works.

At that point in our conversation, the artist herself mentions Hockney and his short film about the Chinese scroll. I am amazed, having decided not to mention him, unsure as to whether she would welcome the comparison. We discuss the fact that Hockney was one of the earliest Western artists to visit China post-Mao – with poet Stephen Spender in 1982. “He learned Chinese aesthetics, and Chinese paintings, and I see that,” she says. She tells me a story, then, about when she was an art student obsessed with early 20th century Modernism, copying a Matisse. One of her lecturers said, “Aha! Matisse learned from Eastern art and now here you are copying Matisse!” She sees the irony in this, and in the fact that Chinese art students inherit a western tradition of rigorous, highly technical academic training which the west has long since abandoned.

Wenmin Li Red Bathroom, 110×75 cm, Mixed media on paper 2004, image courtesy the artist.

I ask her why her work is often described as exploring the disconnection between her Chinese upbringing and her life in Australia. She thinks for a moment before saying, “This disconnection has been a feature for years since I came here. In China I wanted to be modern, a contemporary artist, a Western artist. My dad actually is a Chinese traditional painter, and I always liked Chinese philosophy but I never considered myself traditional at all. It was not until I came here that I realised how traditional I am, and also how little I knew about my own culture. I knew I should have learned more. My new life in Australia has taught me what I didn’t know, in a way. That helped me to see myself in a different way. The distance from China helped me to see myself more clearly.” In a new culture, she says, “You start to re-evaluate who you are.”

Li arrived in Australia in 2001, and rarely returned to China until recently, when she began travelling between her two cultures more frequently. She speaks of the unnerving experience of no longer recognising her home town; everything in China has changed so much, and so quickly. “It’s such a strange feeling – the streets I used to walk down every single day became so unfamiliar and so different. It’s so disorienting and I didn’t feel comfortable at all,” she says.

I am curious about how her work transformed after her arrival in Australia. I had assumed that, like other Chinese-trained artists, she had been taught the traditions of ink painting in childhood. Not so. She tells me more about her early life. “Dad is a traditional brush painter. Having a dad at home like that, a daughter could never follow! I had no interest at that time, and dad was so disappointed – it was not my interest at all. At the age of about 16, though, I decided to study art, and began a very western training.” She did, however, learn some calligraphy. “Dad forced me!” she says.

Our interview continued, sitting in the window of the gallery, over coffee and peppermint tea. What follows is just a small part of a long conversation.

LG: It seems there was a very big shift when you came here – would you define that as the biggest change in your practice or had you already started drawing and printmaking in this new style?

WL: No, not until I came here.

LG: What brought you to Australia?

WL: So many different reasons – I wanted to study western art, American visas were very difficult, and Australia was very welcoming. I had always wanted to go out (from China) and my parents were very supportive. I always believe in fate and I thought it was just time.

LG: So almost by accident you arrived here rather than America!

WL: You could say it was an accident or you could say it was destiny. I was destined to come here.

LG: So when you came here, what changed ,and how quickly did it change?

WL: First I had to learn English and pass exams, and I was enjoying this new environment, so at first making art was not my priority! Then I came to COFA and began an M.Art. COFA was so different to Chinese art training, which is highly technical rather than conceptual, I needed to have ideas, and contextualise my work. It is difficult – we go to Luxun (Fine Arts Academy) now to do workshops with students in drawing, and it is very difficult because technically they are better than students here but the concepts, ideas, the understanding of what painting or drawing can be is just not developed… Once I was here (in Sydney) I have been focusing on drawing a lot more. Initially I worked with acrylic, as oil paint was too expensive. I realised in 2003 that I wanted to do the MFA and so realised that my study had not finished. That was a big life change! It was my supervisor Mike Esson who really changed my view of things. He said “…Why not look at Chinese painting and see if there is anything that relates to you?” For about a month I was reading books from the library, looking at pictures of traditional art and folk art to see what I can do with that…then I just came up with drawings from around the home, my kitchen, my bathroom, the things around me and came up with something new. I changed overnight what I was doing.

Wenmin Li, Blue Rainy Winter 30 x 30 cm earthenware, underglaze colour and ceramic pencil 2009

LG: Mike Esson suggested you look into your own background and your own tradition?

WL: Yes, until then I had not really looked at myself, but after that I started to see myself in the things I was drawing.

LG: When did this very spare, minimal use of line and space come into your work?

WL: During the MFA I started to realise I liked space very, very much and then looked at Chinese traditional painting to see how they compose and how they use space, the three different viewpoints and so on. This multiple perspective in Chinese painting gives viewers a lot of freedom, you are not restricted to a fixed viewpoint. I looked at mark-making… and I looked at Paul Klee, I just used paper, and worked intuitively… I wanted to break the boundaries of the techniques which I had held so tightly. Somehow these works are different to me – the early works are more intuitive and innocent in a way but now there is more consideration, [they are] planned more in terms of line and composition, they are more mature, but there is something I have lost, that intuitive freedom.

LG: Working in a new language also changes your identity in a way?

WL: Yes, absolutely.

Wenmin Li, A Stubborn Bird, 28.5 x22.5cm, mixed media on paper, 2011-2013, image courtesy the artist

LG: How does a work like this one (“A Stubborn Bird”) come about?

WL: They all have something in common. I don’t plan anything. Something happens in my life, I see something, or I just stand there and look at the paper. Very often, most of the time, I start with something – a plant, a bird, a chair. It’s just daily life. And it starts somewhere on the paper and just builds around this. Having developed this new and more personal idiom, Li decided to try working on silk, that highly symbolic Chinese material, as well as paper, aiming for a floating, loose, airy quality. “There are many hidden layers of Chinese-ness in the patterns, tones and imagery” she tells me. I see the lotus flowers, and crows – highly resonant and symbolic visual codes in China. But Australian birds like magpies and mynahs also make an appearance, as well as garbage bins, suburban rooftops, and TV aerials. “I am in between two cultures, I am in this overlapped state – or maybe in the gap between,” she says. The fluid line in Li’s drawing and printmaking is connected with notions of journey, of diaspora. “The lines I use, because I like Chinese calligraphy, there are influences hidden there from traditional Chinese culture…somehow this emerges in my practice.” What’s next? I ask. “I just let it happen,” she says, “But I want to work out how to put this (Chinese tradition) into my practice, into a contemporary practice, so that it is more than just appropriation. Somehow this requires a lot of thinking.”

Right at the end of our conversation, I ask her what her father, the traditional Chinese painter, thinks of her hybrid works. She tells me a poignant and dramatic story. Trained as a western oil painter, her father graduated as the top student from Luxun in 1957. He was supposed to stay in the college as a lecturer, but this of course was the start of the Cultural Revolution. Because he spoke out, he was sent to a remote area of Gansu Province to work on a farm. Somehow, by pure chance (or perhaps Wenmin would see it as destiny) he met the last surviving student of famous ink painter Qi Baishi, and learned from him secretly, kneeling on the floor to practise his brushwork and calligraphy. Now in his 80s, he has worked within the discipline of ink painting for more than 50 years. After the madness of the Cultural Revolution was over, he returned to the university to teach painting, but always had a dream of combining eastern and western traditions. On his visits to Australia, now, he sees that the daughter who resisted his encouragement as a teenager has done just that.