George Shaw on New York City’s public art…

If it were Thanksgiving Day right now, it would be my turn at the table to stand up and declare what I am grateful for. While most people tend to take a big picture view and give thanks for the broad basics of life such as family, friends, God, and health, I prefer to be a bit more specific. For example, at the moment, I couldn’t be more grateful for the opportunity to live in one of, if not the art capital of the world, New York City. As an observer, collector, artist, and chronicler, I could not have chosen a better place. Data gathered from various official, expert, and commercial sources, suggests there are about 750 art galleries in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens ranging from artist-run-spaces to multi-national juggernauts; from the very matte to the exceedingly glossy. Rough estimates also indicate there are 100 museums spread throughout the city’s five boroughs. On average, I visit around twenty-five art galleries a week to look, think, photograph, and find material for future writing. I also manage a few museum and auction-house exhibitions here and there, now and then.

Anish Kapoor, Descension, 2018 (Source: Public Art Fund)

If I am honest, the almost pathological need to engage with art in one way or another every day is no longer what drives me; these days it’s its creepy cousin FOMO, that simmering, quotidian fear of missing out on so many great exhibitions, artists, and works that are available on any given day (Mon to Sat–10am to 6pm, Sun–11am to 4pm). But even when I slide FOMO in one pocket, fold an A4-long list of galleries into another, and wish my left bunion (Made in NYC) all the best, one of the most personally satisfying aspects of this city is the way it embraces public art with vigour, acuity, and generosity. So that even if I’m nowhere near an arts neighbourhood, gallery or museum, I am still rewarded by the quantity and quality of art out in the open on pedestrian islands and footpaths, in parks, plazas, fields, atop buildings, and underground in the subway network. Some of it is permanent and some temporary. Some of it is by artists whose names have been forgotten and some by today’s arthousehold names. Some works manage to retain the aura of art while others have been transformed by their popularity into ‘destination’ Instagram backdrops or, even worse, props. Thankfully there are organisations such as The New York City Department of Parks and Wildlife with its 50-year old Art in the Parks Program; Creative Time; Percent for Art; MTA Arts & Design who commission artworks to be rendered as mosaics in subway stations; Friends of the Highline and its High Line Art public art calendar; and the venerable Public Art Fund, to keep the city refreshed and its inhabitants engaged with imaginative and carefully conceived presentations.

Anish Kapoor, Descension, 2018

It’s hard to believe that it took until 1967 for New York City to stage its first large-scale outdoors public art exhibition, which was organised by Doris Freedman, one of the city’s first directors of cultural affairs, who ten years later founded Public Art Fund. Freedman’s vision was to develop programs that would explore the potential for art to become an integral aspect of urban public spaces, especially at a time when the city was financially bankrupt; showing signs of metastasizing disrepair; and becoming infamous for its escalating crime rate. Out of this miasma of crappiness came Freedman with ideas about installing contemporary art of international scope in public spaces as civic improvement and morale booster, through high-profile artists’ projects, new commissions, and exhibitions. Since those early days, Public Art Fund has presented more than 450 projects throughout the city’s five boroughs, at times incorporating major landmarks such as Times Square, The Rockefeller Center, Brooklyn Bridge Park, Columbus Circle, and The Lincoln Center.

Public Art Fund gained notoriety in the early 80s with Messages to the Public (1982-1990), an exhibition series that ran on an 800-square foot animated light board in Times Square and featured more than seventy artists including Guerilla Girls, Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger, Alfredo Jaar, Richard Prince, and Keith Haring, who addressed the political and social status quo of the times with insightful and challenging works. In the summer of 2017, Public Art Fund facilitated the installation of Anish Kapoor’s Descension (2014) at Brooklyn Bridge Park. The work is a 26-foot-diameter whirlpool that converges in a central vortex giving the impression it is being sucked into the depths of the Earth, aided by a rumbling basso profundo hum, possibly a tad more evocative than the continuous attempts to empty the pool. As a quick aside, when Descension was installed on the grounds of the Palace of Versailles in 2014, conservative critics choked collectively on their Remy Martin and decried the work as nothing more than a gigantic urinal defiling the palace’s hallowed grounds.

Ai Weiwei, Arch, and detail, 2017

Ai Weiwei, Gilded Cage, 2017 (Source: Public Art Fund)

Ai Weiwei, Odyssey 3, 2017

Ai Weiwei, Banner 101, 2017

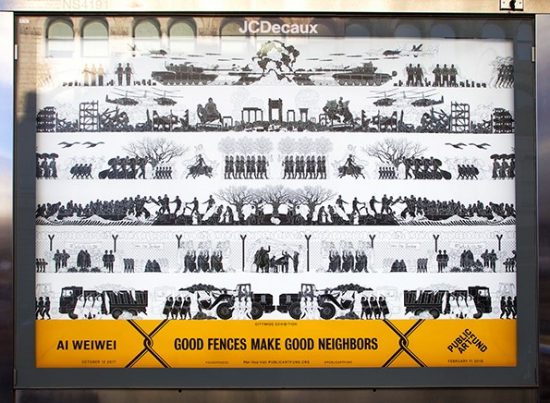

Kapoor’s project was followed at the end of last year by Ai Weiwei’s Good Fences Make Good Neighbors (2017) throughout New York and neighbouring boroughs. The work was inspired by the international migration crisis and global politicization of despair. The program involved 300 pieces ranging from large, site-specific sculptures to ‘interventions’ in the form of wire fencing between buildings, as well as smaller sculptural installations, street pole banners, posters, and documentary photography. For six months, one of New York’s favourite adoptee’s owned the city. Most recently, Wind Sculpture (SG) I (2018), a new Public Art Fund sculpture commission by Yinka Shonibare MBE erected at the south-east entrance of Central Park (opp. The Plaza Hotel), continues the theme of migration with a 23-foot-tall, hand-painted form featuring multiple twists and deep folds that allude to an untethered sail billowing in the breeze. The colours evoke Shonibare’s Nigerian childhood before migrating to England. The batik pattern references Dutch colonisation and trade in Indonesia and West Africa, as well as acknowledging New York’s own Dutch colonial heritage.

Yinka Shonibare, Wind Sculpture (SG) I, 2018

From Agnes Denes’ Wheatfields For Manhattan (1982) in which two acres of wheat were planted and harvested on the Battery Park landfill, a site worth $4.5 billion, to Olafur Eliasson’s The New York City Waterfalls (2008), four man-made waterfalls of monumental scale on the Brooklyn waterfront, Public Art Fund continuously challenges perceptions about what public art is and can be – one of its projects was a season of performative talks by Martin Creed. Public Art Fund, like virtually all other organisations dedicated to public art in outdoor spaces, is a non-profit organisation the exists solely on philanthropic grants and contributions from individuals, corporations, and foundations to carry out its work. To everyone who has ever put their hand in their pocket to make a contribution, I say: Thank you.