It’s 11am, Sunday morning, outside the Museum of Contemporary Art. We have returned to have another look at the Biennale of Sydney and to take note of the contributions of the seven Australian artists in the show. As we are about to enter, a young man lurking near the main entrance to the gallery suddenly steps forwards and asks us if we are here to see the Biennale. When we tell him we are he wonders if we will do him a favour – would we have a look at a special work installed near the children’s section of the gallery? This is all very confusing. First of all, this young man is wearing a black, beautifully cut suit with a black shirt and tie and has a red dice ear ring. Second, a group of his friends are sitting on the fence nearby snickering at his question. Thirdly – is there a children’s section of the gallery? This all seems very suspicious. Is he an artist? Artists don’t wear suits! Sure, he says, my name is ____________ and I have been making contemporary art for the past few years. There is a sculpture of a spider on the ceiling of the children’s section of the Biennale. He says it’s very hard to see, but if we’d just have a look at it and when we leave the gallery, tell him what we thought. He seems sincere and so we agree. Of course, there is no ‘children’s section’ and as we walk around looking for spiders, realise the whole task is some sort of gag. When we leave the gallery he is long gone and as we have coffee and laugh at being so good naturedly duped, we realise his name was an anagram of Biennale of Sydney: Zones of Contact. Oh you crazy artists….

Strongest of the Strange – paintings by [clockwise from bottom] Isriel Adams, Conrad Ross-Smith, Tamara Mendels and Nicholas Pike.

Courtesy G&A Studios.

Gags and art. Art and gags. There just aren’t enough of them. Certainly not many good ones. The four person painting show The Strongest of The Strange at G&A Studios frames its action with some jokey profiles of the artists. For example, Nicholas Pike [it says on the room sheet] is “king of the Sydney underworld. He spends his time in Kings Cross and Woolloomooloo dispensing justice on behalf of his red right hand.” Describing herself as an orthodox Jew, Tamara Mendels’ mission is to “placate the unfortunate by providing calming, lyrical abstract paintings” while Isriel Adams is “a direct descendent of Master John Adams, sole male survivor of the Mutiny on The Bounty” and “is well qualified to present guttural abstract expressionistic paintings.” Conrad Ross-Smith “is wanted on charges of conspiracy by numerous secret societies.” Far be it from us to criticise anyone for their jokes, but the problem here is this: if you’re going to make jokes about yourself, you’d better be sure the work lives up to the quality of the joke – or in some cases, lives down to it. Accompanying these admittedly amusing profiles are some fake quotes from Liz Ann Macgregor, Gene Sherman, Anne Gregory and Matthys Gerber each saying silly things about the artists. Enough already!

It was our first time to G&A Studios and we have to say it’s a very handsome space – high ceilings, good lighting and the red strip on the floor that leads you from the front door to the gallery is a welcome sight for those scared witless by the unkempt bohemian surroundings. Once inside, The Strongest of The Strange – apart from all the slightly tiring gags- is an interesting insight into the miniature world of painting at Sydney College of The Arts. All recent SCA graduates, each of the artists in the show seem to embody a particular and currently popular approach to making paintings. Ross-Smith paints on old paintings, blocking out backgrounds, leaving tiny details, turning what had been a field into a solid yellow wall. The best of these works is called Ship and it’s a junk shop picture of on Old Spice style vessel with its sails painted out an unsightly red. Ross-Smith’s closest cousin in the show is Pike, who’s on a Shrigley-esque trip of fast, gestural paintings with ironic text painted over the top. Our favourite was one which featured words that didn’t quite fit on the canvas – A little speed and housework turned out to be Special K – and everyone knows how that feels. In contrast to these two painters, Adams works on paper are a little bit of everything – splash, dribble, scribble, a little figure swooping up, all of it done very fast. Mendels too is gestural, but probably more calculating – she works with acrylics, resin, enamels and varnish on board, painting patterns, then pouring paint over the top. The result looks like a three-way fight between David Larwill, white-on-black period Imants Tillers and Matthys Gerber smoking a rollie – and it looks like Larwill wins. Mindful of the shellacking we got two weeks ago when we reviewed Rob McLeish’s show at Esa Jaske Gallery, let us just say this. It was really great to see young painters getting together and having a show of their work because it’s quite rare in the artist run gallery scene, but the jokes sort of ruined the experience. If you don’t take it seriously, who will?

Tim Silver, Untitled (killling me softly) version 4.11, 2005/06.

Archival ink on archival paper, 30×45.5cm. Photography: Jamie North.

Edition of 6. Courtesy GrantPirrie.

Speaking of getting a drubbing, we were upbraided by some readers for not going to certain galleries, not agreeing to certain points of view and – in general – not trying hard enough. We stand before you ashamed. We missed Tim Silver’s show Killing Me Softly at GrantPirrie. It had been well received by movers and shakers including Rene Block, who was in town for the BOS, and who has selected Silver’s work along with recent series of photographs by Rosemary Laing for the forthcoming exhibition Art, Life & Confusion: The 47th October Salon staged in Belgrade from September 29, 2006 [not the Budapest Biennale as we initially reported here]. We did catch the second last day of Silver’s show and have to admit to being a bit disappointed. Silver’s early works utilised their materials in a very clever play with what they purported to represent. Our favourite earlier work Untitled (Adrift) from 2004 boat made out of reconstituted blue watercolour pigment which sat in a tub of water slowly dissolving into the liquid. Silver documented the process with a series of simple images. It was an elegant conceptual piece, thoughtful and multilayered in possible readings. In Killing Me Softly, Silver used the same kind of process, this time making skeletal bodies out of compacted soil. The still images and the obligatory DVD documented the slow disintegration of the “bodies” – one in a Belangalo style bush grave, the other on a beach, unavoidably evoking From Here To Eternity, a clever play on the process and the image. Despite the conceptual continuity, the show seemed oddly unresolved adding in new theatrical layers that obscured and confused what had been such a pure process. The eccentricity of the work is still refreshing and despite our misgiving you can see why Block was so taken with it.

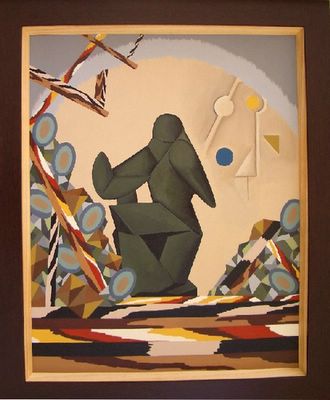

Diena Georgetti, When I’m suffering, bring me an animal, I don’t care if it’s alive or dead,2005. Acrylic on canvas, 88x73cm.

Courtesy Darren Knight Gallery.

The eccentricity of Diena Georgetti’s work is hard to deny. We had seen a selection of pieces from her latest show The Humanity of Construction Painting at Darren Knight Gallery in the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art when we were in Adelaide in March. Context is everything. Her work in that show seemed too much effort to take in but in her show at DKG – seen en masse – we rather liked them. What had changed? The Adelaide Biennial had gathered together scores of works which made explicit reference to Modernist art and in that context Georgetti’s work seemed unusually orthodox. In her DKG show, however, the feeling of the show is one of a fascinating expose of the artist’s intense enthusiasms, some of it bordering on the obsessive. The small-scale paintings, done on board and canvas, combine motifs gathered together from various early 20th century modernist art movements – patterning courtesy of Bauhaus fabric design, a little bit of Suprematism, a dash of Futurism, some nods to Alexander Archipenko, a bit of Outsider patterning – all of it coming together into museum-like framing. You can see why Linda Michaels, the Adelaide Biennial curator, snapped them up for her show. On one level they seem to conform to the idea of orthodox Post Modernist appropriationist painting, but on another they seem far more loving and downright perverse than clinical, museum-ready examples. Apparently the artist imagines a perfect space where these paintings might hang, Darren Knight informing us that one would be best seen hung over a Parker credenza. We imagined the wood grain of such a furniture item and Georgetti’s painting hanging over it, and with it came thoughts of deep carpet and the loud ticking of a clock in the hallway.

Sarah Ryan, Sun, 2006.

Digital lenticular photograph, 60x60cms.

Courtesy the artist, Gitte Weise Gallery, Berlin & UTS Gallery.

Another artist whose work we didn’t appreciate much on first viewing is Sarah Ryan, one of the seven artists included in the superlative new show Art Movement: Explorations of Motion and Change at the UTS Gallery at the University of Technology. Our first sighting of Ryan’s lenticular photography was in the Citibank Photographic Portrait Prize where she had done a portrait of someone not famous lying on a floor in a big room. Called Tender, we couldn’t quit get why she had used lenticular photography for the subject – it seemed like a gimmick – or maybe she just liked it. Either way it didn’t really work. In Art Movement however, Ryan has done an image of light as seen through tree branches and leaves. Lenticular photography is type of imaging like those 3D post cards where you change the angle slightly and you get a slightly different picture. In Ryan’s Sun, the process has captured the exact experience one has when you alternate opening and closing your eyes one at a time, or perhaps moving your head ever so slightly. The effect is mesmerizing – like the warm sun on your face and the wind in the trees – it makes you sleepy.

Daniel Crooks, Elevator No. 4, 2003.

Still DV/DVD, 6:645 mins dur.

Courtesy the artist, Sherman Galleries and UTS Gallery.

Curated by Ricardo Felipe, the man behind the excellent Avalon book and exhibition, Art Movement brings together a range of artists [and architects] who address motion as metaphor in their work. Daniel Crooks video works Static No. 9 [a small section of something larger] 2005, and Elevator No. 4 2003 would be the best known works in the UTS show, both having been seen in exhibitions before at Sherman Galleries and the MCA, but are the perfect starting point for metaphor. Crooks’s videos are among the best video art made in this country for the simple reason he uses the medium in a way that no other medium could capture. Instead of the lo-fi pick-it-up-and-shoot-edit-it-in-iMovie ethos of so much video work around, Crooks uses it to make something absolutely magical that would not be able to be achieved outside the digital realm. While the work does indeed echo the work of film makers like Paul Winkler, video technology is the centre of its own possibility. And more than that, every time we see Crooks video work we feel good. Yeah.

John Tonkin, Time and motion study [holding on, letting go], 2003-2006.

Interactive installation. Courtesy the artist and UTS Gallery.

Another outstanding work is John Tonkin’s Time and Motion Study [holding on, letting go] 2003-2006. As you walk into a darkened room, a web cam captures your image and feeds its low grade jittery frames on to the expanse of an LCD widescreen TV. As each new image overlays the last, the older image appears to fade into the background. [Tonkin in his catalogue notes cites Amy Stewart‘s Knock on Wood and Michael Jackson’s Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough clips as historical examples of a similar technique]. Next to the screen in a plinth with a computer mouse on top of it. As you pull the mouse towards yourself, the decaying images that faded away behind your face march backwards, revealing all the shots of your face but then, the further you pull the mouse towards yourself, the older the images become until you start to see the captured faces of people who walked into the installation before you. Move the mouse side to side and you see the images from the side in 3D, like a parade of cut out faces. Tonkin might be thinking King Of Pop here, but we immediately thought of Plato and his allegory of the cave. Tonkin’s work is a contemporary oracle, revealing the faces of time present and past. Like Crooks’s videos, Tonkin’s piece demonstrates why contemporary art – when it combines technique, idea and execution so brilliantly – truly matters.

Robert Pulie, Task for no pencil sharp enough, 2005.

Looped DVD, 10:38 mins dur.

Courtesy the artist, Mori Gallery and UTS Gallery.

The rest of the show is up and down, not quite equaling these three excellent works, but come awfully close. Robert Pulie, on a similar Plato-esque tip to Tonkin, attempts to trace his own shadow in the video work Task For No Pencil Sharp Enough, 2005 and in Auto-Propulsion Bit [prototype] 2006, Pulie offers up a joke shop object by which the purchaser can pull themselves along, both works playing on their own impossibility as an action and as an idea. The inclusion of the architecture firm m3architecture may be some sort of sly reference to Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe‘s remark that architecture is frozen music and, while certainly demonstrating the curator’s pleasingly wide definition of what constitutes movement, the inclusion of plans for a building at Brisbane Girls Grammar School is still a little perplexing. A building that moves? We’d like to see that! Elsewhere in the show the concept goes a little astray – Tonkin’s second interactive computer work was frozen while Tom Burless’s Anything Can Happen, especially nothing/This is where I came in, 2006 lives up to its title. These are minor quibbles though as the show overall – including an excellent essay by Gabrielle Finnane – is the kind of thing people who love contemporary art know should exist but so rarely does. Mr. Felipe, move back to Sydney immediately.