Luise Guest investigates the great sculptural metaphor…

The ghosts of some artworld figures past and present are invoked in Chart at William Wright Artists’ Projects on Stanley Street, a show of installations by Tony Scott and Anne Graham. Duchamp is here, and Beuys, and in some works the sardonic iconoclasm of Ai Weiwei makes an appearance. Linked by time spent working in China, a central element in the work of each of these artists is an interest in the human body and the ways in which physical sensation and memory reside in objects and the material presence of ‘things’.

Graham’s work on the ground floor beckons the phantom presence of Joseph Beuys, who seems for a moment to be here with us in the gallery, hanging as a transparent apparition on the wall in the form of a suit sewn from filmy white organza. The title of this piece, ‘Nobody,’ reveals the artist’s ironic bent, and a suggestion that we need to look below the seductive surfaces of her works, in order to find the meanings which will reward those who are willing to do so. The use of black and white felt in stacked or sculptural wave-like forms is another deliberate reference to Beuysian notions of the artist as shaman. Graham has participated in numerous artist residencies in Japan, Korea and China, and these influential experiences have shaped her ideas and her material practice, as seen in this recent work.

Anne Graham, Nobody, 2012, Organza, Metal, 162 x 86 x 15 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, photograph Jenny Carter.

Like a number of contemporary artists working with installation and found objects, Graham is interested in the actual physical matter of her works and the layers of possible meaning with which it is imbued. Felt, glass, wax, fabric, timber, horse hair – all these materials evoke both human and animal bodies yet their possible meanings often hover just out of reach. The entire white horse’s tails emerging from the necks of silvered thermos glass bottles in ‘Back to Back’ remind us of the beauty and pleasure, but also the cruelty, inherent in the relationship between human and animal. They are suggestive of ritual, of sacrifice, of desire, but also of loss and mourning. This is further elaborated in ‘White and Black Elephant’ with its transgressive use of materials such as ebony and ivory evoking the presence of the suffering animal.

Anne Graham, ‘Back to Back’, 2011, thermos glass, horse hair, felt, 114 x 200 x 32 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, photograph Jenny Carter

Her use of traditional Chinese stools in works such as ‘Footprint’, in which felt shoe inserts are stacked onto the small wooden stools in a towering bundle tied with string, made me think of the way in which tradition and history is completely and inextricably bound together with the present day reality of life in China and Japan. Traditional Chinese cloth shoes, the practice of footbinding, the veneration of ancestors: all these meanings are suggested in this elegantly minimalist work. Likewise in ‘Steps’, the use of long strips of white felt entwining through a stacked arrangement of Chinese stools suggests so much more than the physical reality of its materials. Her work has been described as ‘transformative reinvention’ and the clever paring back, the recognition that less is indeed more, places her work within the context of artists such as Wolfgang Laib or Anne Hamilton who also work with physical matter in this quite magical manner. And of course, inescapably, the image of those reinvented and transformed Qing Dynasty tables reconfigured by Ai Weiwei in his pre-Sichuan earthquake practice is brought to mind, again suggesting that interweaving of past and present, memory and experience.

Anne Graham, [left] White Elephant, 2012, Felt, Wood, Emu Eggs, 100 x 113 x 36 cm, [right] Black Elephant, 2012, Felt, Wood, Ivory, Ebony, 103 x 130 x 36 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, photograph Jenny Carter

Having lived for many years in Beijing, Tony Scott has of necessity experienced Chinese medicine in both its traditional and contemporary manifestations. As anyone who has spent any time in China will know, this can be both confronting and terrifying. Indeed, Scott’s accounts of life in China during the SARS epidemic definitely fit the category of the cautionary tale. His installations comprised of sinister medical apparatus, often in combination with the traditional acupuncture figures found in Beijing’s Panjiayuan ‘dirt market’ suggest the fragility of the human system and its vulnerability in the face of disease and invasive medical interventions. Scott has said of his practice that he is concerned with the effects of time and the aesthetics of the body, “particularly in reference to the detritus of a rapidly changing society, the loss and reconfiguring of knowledge and the disintegration of my own body.”

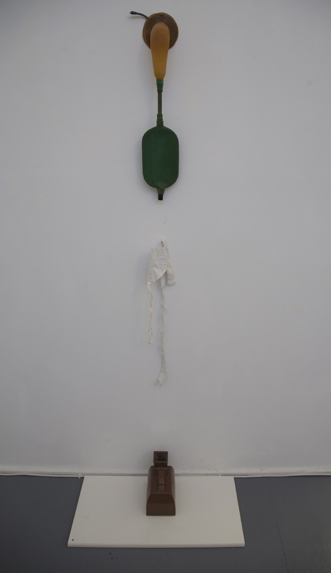

Tony Scott, Incontinence Sheath, 2012. Found objects, Incontinence sheath, incontinence belt, bed pan, Rubber, calico, Various dimensions, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, photograph Tony Bond.

A work such as Incontinence Sheath, which is made, as the title suggests, of an incontinence sheath, a belt and bed pan, and rubber tubing, inevitably evokes Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ in its deliberate mixture of humour, pathos and that slight frisson caused by something taboo brought into the daylight. The objects themselves become the body’s stand-in, in all its inglorious flaccidity and frailty. The found objects used in Breathing Apparatus, include a lung draining machine, stethoscope, and electric current meter, attached to what appears to be an acupuncture training image of the pressure points in the head and face.

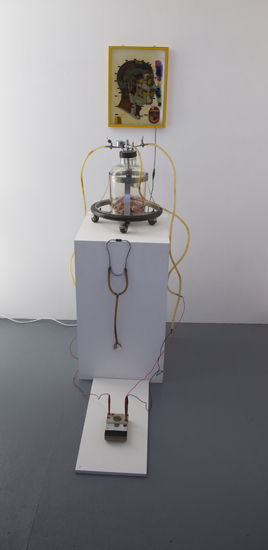

Tony Scott, Breathing Apparatus, 2012. Found objects: Lung draining machine, stethoscope, electric current meter, Light Box, digital print 43 x 32 cm. Installation various dimensions, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, photograph Tony Bond.

These works, similarly to his earlier ‘Health Plan’ and ‘Headache Series’, are tremendously poignant. The wooden figures, which appear ancient but are probably fake, like most of the ‘antiques’ on sale in the dirt market, are riddled with tiny holes showing the points for the insertion of acupuncture needles. They have a silent stoic dignity. Attached to the kind of ancient Mao-era laboratory equipment of clamps, tubes, jars and machines that brings to mind unspeakable processes of medical experimentation, they are suggestive of our helpless reliance on medicine in the face of the inevitable. In these new works the medical equipment itself becomes the proxy for the frail human body.

A confident ability to dispense with the unnecessary and pare back to essential elements characterises the practice of both these artists. The ‘chart’ referenced in the title of the show relates to medical charts, to the charting of physical geography in the travels of each artist and their experiences of different cultures and traditions. It also alludes to charting and mapping memory, and to the ways in which art can translate individual experiences through metaphor, expressing universal truths.