There was this artist we met once who told us all about his early career just after he got out of art school. Experimenting with layering paint and colours, the artist really felt he was on to something, but what he felt he was lacking was a context in which to make his art. Luckily for him, there were other young artists around who got together with him and rented out the only cheap real estate available – a warehouse at the end of a wharf. They had a gallery space and they staged shows. The newspaper started running stories about this art community that had seemingly sprung up over night and soon the artists started selling their work to an appreciative local audience. As time went by, the other artists started to fall away, get married,move interstate or overseas, or just give up being artists for something more financially stable. Our artist didn’t stop making work and he set up his own gallery after the artist-run space closed once the wharf was sold and redeveloped as a shopping centre and restaurant precinct. He also got energetic interstate representation and began to sell his own work for huge amounts to the burgeoning tourist trade. Financially successful if critically ignored, the artist and his wife live well and travel the world to see the latest stage musicals in New York and London.

This is a story that, when we heard it, made us realise that the art life is nearly universal in the way it plays out. Some artists prosper, others die away, while still others stay exactly where they are for years and years and years. It doesn’t matter that the artist’s name is

Dean Vella or that the hot bed of artistic activity was in the tourist town of Cairns in Far North Queensland in the early 1980s, as far as the broad details are concerned, this is a story that could have been played out in Melbourne, São Paulo, Montreal, Hong Kong or Mumbai. So long as someone remembers Paris in 1871 or New York in 1947 or Sydney in 1969 or some other bohemian meeting of artists and writers and other allied tradesmen, then we’re living la vida art life.

It is curious then that the Museum of Contemporary Art is hosting Situation, an exhibition that looks at three artist networks in Sydney, Singapore and Berlin. We say ‘curious’ because there seems to be no particular impetus behind the idea for the show apart from the fact that it probably seemed like a good idea. While we certainly welcome and encourage the MCA in its efforts to connect with the local art community of Sydney, these questions must be asked: Why now? Why these artists? Why these cities?

The artists representing Sydney in Situation do indeed make up an extraordinarily active group that includes Lisa Kelly, Alex Gawronski, Sarah Goffman, Simon Barney, Elizabeth Pulie, Anne Kay and Jane Polkinghorne. If there’s a show on anywhere in this town, they’re probably involved in some way, and if they aren’t, then they probably know about it. As to how representative this group of people are is to ask the wrong question. These artist’s never set out to represent anything other than their own practice, but we’re sure that some people – including us – would think, why not me? Why not include me and my friends in this show? We’re all connected to this exhibition in some way and since there’s fewer than six degrees of separation between nearly everyone who reads this blog and the artists involved in the MCA exhibition, there is indeed a very real expectation that they represent us.

In this sense, Situation is not representative of all Sydney art – Sydney Situation is mostly conceptually and theoretically based, non expressionist and somewhat self conscious. [None of that is a criticism, by the way, just an observation of the artists and their show]. The non-conceptual, non-theoretically based, expressionist, unselfconscious artists will just have to wait – but they may be waiting a very long time. The major difference between the Sydney artists in Situation and most others is that they are acutely aware of the idea of an art community – from publishing magazines, launching web sites and going to seminars to organising campaigns, starting galleries and applying for funding – these situationistas actively promote and document everything they do. While there may be many informal artist networks out there equally deserving of recognition, this one is vocal, visible and museum-ready.

So why these cities? Apparently Sydney, Singapore and Berlin each have about 4 million people and as the MCA press blurb explains they are positioned as “cultural hubs for their regions, yet away from the traditional centres of London, Paris and New York. In each, vibrant artistic communities flourish, often away from the public eye.” We have our own limited experience of the Singapore art scene and know Sydney pretty well, but Berlin’s art scene remains a mystery. We’ll just take it on trust that the art scenes of many other places – be it Cairns or Amsterdam or Johannesburg – weren’t as interesting or worthy of inclusion or maybe the MCA just couldn’t afford it – but since one is representative of the others [and the Situation artists seem to be all connected by international travel and the informal web of alternative art spaces, magazines and exhibitions] – why not feature Sydney, Singapore and Berlin?

Singapore – that strange city of government mandated creativity and feel-good arts festivals – is represented current and previous members of The Artists Village, an artist’s collective established in 1988; Lee Wen, Juliana Yasin/Colin Reaney, Tang Da Wu/Jeremy Hiah, Kai Lam Hoi Lit, Agnes Yit and Koh Nguang How. Berlin is represented by Sparwasser HQ, an artist-run space established in 2000 that “emphasises research, communication and dialogue” and features the work of artists Lise Nellemann, Ariane Müller, Egill Sæbjörnsson, Jole Wilcke and Tino Sehgal. We’d never heard of any of these artists, but the chance of seeing all this stuff together and all of it from intoxicatingly exotic places, and with the question of what the Sydney artist would do, we skipped into the MCA like little school girls.

Disturbingly, the Sydney Situation artists seemed content with documenting their work rather than showing their work, or indeed, their work was a process of documentation, so it all looked rather similar. And that means one thing: a lot of reading. There are magazines and posters and other ephemera scattered about, wall texts, name and detail labels, explanations, and instructions. After a while it started to feel like watching SBS. Enough with the subtitles, people, let’s have some singing! And then there was a burst of song and it sent a cold chill through us that froze the very marrow in our bones. For one horrible moment we thought someone had recorded that woman who used to walk down the middle of Oxford Street singing fake opera at the top of her lungs, and who everyone thought was a charming eccentric, but who was in fact a very scary person with a voice like the sound you will hear on Judgment Day. It turned out to be part of a video projection but it still set us on edge.

Alex Gawronski’s work Untitled 2005 is almost the first thing you see when you walk into the MCA gallery. Following a set of typed instructions, the gallery visitor is invited to sit down and listen to tape recordings of what other visitors have said about the show. We hadn’t even begun to look at the show and already we were in the process of reliving it. We selected a tape and put it in the tape player. PRESS PLAY. Nothing. We rewound the tape all the way to the start. Still nothing. We turned the tape over and rewound it again until we finally found some recordings. Unfortunately the volume on either the original recording or the playback was so low we couldn’t hear a thing, just some distant, indistinct chatter. We read the wall text that said in part that Gawronski’s work was “often concerned with bureaucracy”. Things must have got all balled up at head office.

Next to Gawronski’s work was a wall devoted to the work of Simon Barney, the artist many have credited with starting The Art Life. A relaxed conceptualist, Barney’s work invites visitors to fill in some cards with suggestions for subjects for his paintings. On display are some paintings he’d done earlier – a vase of flowers, a billboard and the crowd favourite, a portrait of Elizabeth Ann Macgregor done as the Queen. We read through the cards and felt that some people hadn’t quite got into the spirit of the thing. “Please paint something with absolutely no ideas” wrote Catherine Lasser. Another visitor asked if Barney would please do a picture of a Chinese Punk band [or similar] for the visitor’s private collection of Chinese punk bands. Our favourite – and the one we’re hoping that Barney will do – was from someone named Sam Gooburg that asked “A pig in a small boat in a raging river”. We think you’d agree, such a painting would have much visual appeal and be loaded with many symbolic readings; pig, boat, raging river. Alongside this is documentation of Barney’s Briefcase gallery works and a rather wonderful collection of crappy slides donated to the artist’s crappy slide collection. Sadly, there was no mention or inclusion anywhere of Barney’s Art Life Project or documentation of the great day that the artist posted the very first posting in February 2004. We can dream!

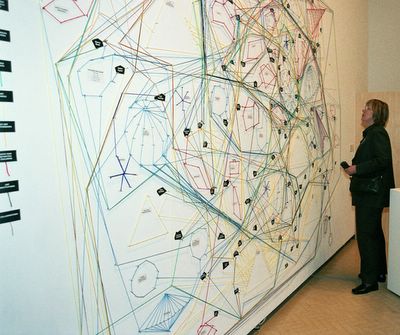

As we wandered through the show we thought back to Perspecta in 1991 and the exciting thrill of seeing all these people we know and their work in the glare of the museum lights. Sarah Goffman’s cut bags hanging on the wall like the flags of many nations and Lisa Kelly’s studio simulacra, Elizabeth Pulie’s latest Situation-linked special edition of Lives of The Artists. Just like the Easter Show! The oddest piece in Situation is Anne Kay and Jane Polkinghorne’s Artist Archive Map 2005 that charts in a very idiosyncratic way, certain connections between artists, galleries, publications and personalities.

Now, where’s COFA? Anne Kay and Jane Polkinghorne’s Artist Archive Map 2005 at Situation.

The links are made of coloured thread and built up in various patterns, which, if you get back far enough, you can see that they make pictures. But we spent most of our time up close looking at the names spread out on the wall. It’s a completely personal and non-scientific flow chart of associations that seem to make little sense from an objective point of view. For example, few would argue that Mark Titmarsh isn’t a seminal figure in the Sydney art scene with all his various activities since the 1980s from the Sydney Super 8 Film Group to On The Beach to Art Hotline to Sydney College of The Arts to Artspace to Brisbane to New York to San Francisco to Caracas. He’s been everywhere man. But is the “Mark Titmarsh of the New Millennium” Lucas Ihlein of equal importance? OK – Bilateral, National Union of Uncollectable Artists, Sydney Moving Image Coalition, etc, etc? But is it all the same? Is it all equal? And then there’s Barbara Campbell on the wall and Dr. Brad Buckley and Elvis Richardson, Sydney College of The Arts, MOP, The Wedding Circle, Haiku Review, Lives of The Artists.

It’s a weird collection of names and things and places. RubyAyre but not Gallery Wren, Art Unit but not Art Network, Mark Titmarsh but not Michael Hutak, Buckley but not Alan Cholodenko, SCA but not COFA. According to the amount of wool given over to the Sydney Art Seen Society, you’d think it was the most important and influential grass roots arts organizations ever, even more important and influential than the Contemporary Art Society. As much as we love flow charts and diagrams and spent ages looking at Kay and Polkinghorne’s work, it was frustrating – time and space and people and places do not exist in their world as it does for us. For the artists in Situation, they are at the centre of the universe.

Leaving behind the Sydney artists and continuing into the Berlin space it soon became apparent that the game plan for the whole show is a superabundance of documentation. No wonder John McDonald hated it so much – there’s “nothing” to “look at” in the traditional sense. Lots of books and magazines and video screens, charts and projectors and headphones and those forlorn booths where the hapless punter leaves their inaudible messages for Gawronski, but few paintings and tons of stressed out materials, crappy objects and bargain basement mounting. The Berlin space was more of the same and so was the Singapore space at the top of the stairs.

Did we really care to see more of the same? Did we really want to engage with artists who made work rather like the work made by people we already know? The answer was a dispiriting no. We don’t. It’s not that we don’t value the contribution of other artists, or are disinterested in their cultural context or anything else, it’s just that the truth of it is we’re looking for the next Dean Vellas, wherever they be from. Although we accept the idea of context and community, we are all individuals [as they say] and the best thing this show could have been would to have been about 100 times larger, have only been about Sydney and connected every single artist and art world person together past and present. Then we’d really have something amazing.