Near the beginning of the sculpture walk at Gallery 460 and Sculpture Park there is a metal table with three cans of Aerogard placed on it. A notice advises you to lather up before you set off. How we laughed. Perhaps they should leave gin and tonics so the quinine can help fight malaria! Ha, ha. Actually, if you should find yourself at Gallery 460 & Sculpture Park, we advise you to take the offer seriously. The sculpture garden near Gosford is set in rolling hills with streams and ponds and little bridges. Bellbirds call out plaintively from tall rainforest trees. It is a restful, contemplative place suitable for family picnics, where children might play among the huge metal sculptures, such as Laurindo de Abreau Soto’s massive wave sculpture, a gigantic yellow object with a gargantuan arm balancing precariously. It’s a marvelous setting but in the rain the place is a swirling humid swamp where swarms of mosquitoes are so large they could easily be mistaken for fuzzy grey sculptures that can fly through the air. Run for your lives!

Pretty much everything in our collective imaginations was formed in the 1970s watching cheesy sci-fi “classics” such as Rollerball [1975]. The Sculpture Park reminds us of scenes from that film where beautiful people in evening gowns and tuxes walk around fields blowing up trees with futuristic guns just because they can. We had something similar in mind as we admired massive modernist sculptures not usually seen outside of the forecourts of old skyscrapers,or perhaps in those landscaped dead zones next to freeway flyovers. At the G460&SP, the wielded metal monsters with their huge intersecting pieces or the rounded sandstone sculptures where figurative features emerge from abstract orbs and blocks are just so ripe with melanchol they are genuinely painful to look at. The G460&SP is a nature preserve for a lost utopia.

John Winch, Deluge, 2005.

Mixed media, 30x25cms.

Courtesy Gallery 460.

The gallery part of the sculpture park – a free standing building set in landscaped splendour – has space for two shows and the current exhibition is by husband and wife artists John and Madeline Winch. We often wonder how couples who are both artists live together. It says in the exhibition notes that the Winchs have been an item more than 40 years having studied together at The National Art School back in the mid-1960s. Do they share each other’s work day and night? Or do they assiduously avoid mentioning it over breakfast? [‘I see you’ve put Henry VIII in another one of your pictures, dear,’ says Madeline. John ignores her, reading his paper as he dips a toast solider into his egg. ‘Hmpf,’ he says, and then remembers he needs to buy some ink…] Luckily for the Winch’s they have complimentary practices.

John Winch is an illustrator and the author of children’s books including Run, Hare, Run! The Story of A Drawing which it tells the story of a hare that runs away from a hunter, except it turns out that the hunter is Albrecht Dürer. Instead of eating the hare, Dürer draws him, conferring artistic immortality on the bunny, which is then set loose at dawn. “And the wild brown hare lives forever…” As a story, it lacks the interactivity of recent children’s books such as Goodnight Poppy Cat and That’s Not My Monster or even Where’s Maisy?, with their flaps that can be lifted, fur that can be stroked or ears that can be admired. As a sequence of drawings, however, Winch is master craftsman of pen and inks on paper. His new book – Deluge – seems to be about some boat or other with two of every animal on it, and the drawings look great, but we urge the artist to consider giving the hippopotamus a net skirt that can be lifted. Just a thought. Less convincing are Winch’s canvases with the aforementioned Henry the Eighth plonked in the middle, or the head of a horse.

Madeline Winch, Mother and Child II, 2005.

Acrylic on canvas, 90x90cms.

Courtesy Gallery 460.

Madeline Winch would a name familiar to visitors to the Portia Geach Portrait Prize. She’s also had work in the Sulman Prize, the Dobell Drawing Prize and in 2004 she won the Kedumba Drawing Award [the Blue Mountains based acquisitive award that’s just waiting for contemporary artists to walk and take the $20k prize]. For those not familiar with her work, Madeline Winch paints in a deliberately flat, colourful style with roots in early naïve Modernists such as Henri Rousseau. No wonder then that Winch has done a four canvas tribute to the old customs clerk and it must be said, for a series of images that have been done to death by loads of artists without much talent, Winch’s works have both élan and wit. Her more interesting works are of swoony, poetic figures in forests looking at each other with nervous glances. Our favourite image in the exhibition was of a mother and child. Mother is sitting on a chair. Child is on the mat. What is wrong with this picture? It’s all too neat. Either this child has been drugged or its thinking about being forced to read Run, Hare, Run! when all she really wants to do is find out if there’s a crocodile hiding behind the yellow sail in Where’s Maisy?

Jacky Redgate, Straightcut #6, 2001-02.

Type C photograph, frame 75.0 x 98.0 cm, edition 1 of 5. Private collection. Courtesy of the artist and Sherman Galleries, Sydney and ARC One Gallery, Melbourne.

We had been wanting to see Jacky Redgate’s show Life of The System at the Museum of Contemporary Art to find out if there’s any life in it. We’d also been looking foward to the Redgate curated companion show 1967, works from the permanent collection that were made or purchased the year Redgate and her family arrived in Australia. It’s always great to see material from the permanent collection as it so rarely gets an outing and the word ‘on the street’ was that if you were into Op, Pop or anything that runs on small discreet motors, then this was the show for you. Pretty much the first thing you see when you leave the lift on to Level 4 is a video monitor with Jacky Redgate explaining her work. She’s standing in front of a large photo of what appears to be a plastic box with a red stripe on it. Redgate: “Well… um… this piece is… difficult… to… er… enter.” Well yes, it’s a photograph. “And it’s… quite… contained.” It’s a box! It’s probably best if artists do not speak about their work, or at least not to be seen to be speaking about their work in this way. As much as we like to hear about context, this was a video too far.

There is life in the system if you mess with it. Redgate’s work from the early 1980s onwards has been about setting herself limits on her materials and then to see if she can break those limits. Of course, you can always break your own rules because you’re the boss, and who is going to stop you? Early works in the show such as Photographer Unknown 1980-83 are, for us, the most interesting. In the series Redgate used happy snaps from her family’s collection and rephotographed them. Their formal qualities – and they are highly aestheticised – comes from Redgate organising and recomposing the shots – that is, messing with the system. As her works progressed from the 80s onwards, the basic premise for each series became more complex and, increasingly, harder to fathom for the viewer. The highly polished and aesthetic ordering of materials, often displayed in faux-museum style arrangements and settings, were too complex to either assess without contextualising information or were just too obscure. The Straightcut series from 1998-2000 – those mysterious boxes – are a good example. They are indeed hard to enter and if you can what are they saying? Put your shoes in me?

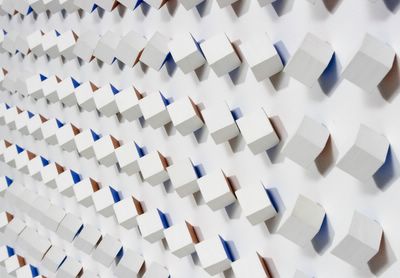

Luis Tomasello, Atmosphere chromoplastique no. 154 [detail], 1966.

Synthetic polymer paint on wood, 90.5×90.5x9cms.

Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Redgate’s selection of works for 1967 makes for an interesting comparison to her work. Concentrating on the highly ordered visual languages of Op and Conceptual art, the show is made up of the sort of work that is the result of an artist following their rules to the letter, never breaking them. Bridget Riley’s Static 3 1967 and Gunther Fruhtrunk’s Von Rut Zu Rot 1967 are works, elegant in their conception and construction and absolutely unbending in their commitment to minimalism. Redgate’s work seems anarchic in comparison. There are a few anarchic works in 1967, but if only by accident. Lily Greenham’s work Study In Visual Perception is a long, green collage on board with three diamond shapes on three panels. Either side are a rack of lights which are meant to go on and off at – we’re guessing – regular intervals. Sadly, they didn’t go on. Hugo Demarco’s Images Variables is a work that is seen under black light. It has little orange and purple balls that go flying around and, if you squint and block out the sounds of the motor driving it, it looks like an animation of sub atomic particles. [We’re imaging that’s what it would have looked like because, on the day we visited, the work was being attended to by three gallery people who were scratching their heads wondering why it wasn’t working properly]. Functioning perfectly was Peter Sedgely’s Chromosphere 1967, a static painting bathed in lighting effects. A square canvas with circles of varying widths and diameters painted on to it, the lights slowly came up and then down again, making the painting grow, change colour, sharpen up, then go furry. Gregorio Vardangea’s Cercles chromatiques 1967 is a series of half spheres, one set inside the other, with lights that come on in sequence – little tick, tick, ticks behind the scene, looking for all the world like one of those fiber optic lamps. These works were, on one level, incredibly naff, and on another incredibly touching. This, children, was the end of painting and the beginning of video.