From Isobel Johnston…

The raven is a bird often seen as a portent of evil or a bad omen. In their absence or their presence there lies the unsettling suggestion that something evil follows. From the six ravens that legend requires be present to prevent the fall of the kingdom at the Tower of London to the Edgar Allen Poe poem The Raven, it’s a bird that is seen as a harbinger of doom.

Matt Glenn, Raven 1, 2009.

Mirror, plastic, high gloss auto paint, 74.5 x 43.5 cm.

Matt Glenn’s exhibition Raven, recently shown at James Dorahy’s Project Space was a tight and beautifully counterbalanced show where gothic mirrors echoed gunshot car duco pieces creating a sense of unease in a space where past and future coexist. Six images reflected the other – the mirrors coated in black baked enamel and the six coloured and steel surfaces. The panels, with their immaculate surfaces ripped through by gun shots (mostly discrete bullet holes made by a .38 calibre rifle but some are blasted with lead shot) captured the feeling of uncertain times both past and present. Raven also acts as both a prompt and aide de memoir for other haunting shows.

The nature of what gets reviewed and what doesn’t seems as random as most other things in life quite often determined by space, time and deadlines as much as by merit. Some shows have a much greater lasting impact than the duration of the exhibition and become cardinal points of reference for other exhibitions, pointers to future directions, often signalling the beginning of a particular artist’s or group of artists’ emergence into the art world consciousness.

Robert Habel, Paessagio Urbano Italiano, Rogues Gallery 2008.

Oil on canvas, 170x170cms.

This afterglow impression of recalling other exhibitions was also tripped at Firstdraft with Visage shown in April this year. Curated by Felix Ratcliff this was a group show of painters. A number of these artists are represented by Gallery 9 and have had interesting shows in the last year or so. Jake Walker had work showing simultaneously at both Firstdraft and Gallery 9. As well as exploring the boundaries of portraiture the idea of small scale painting in a range of media from watercolour to oils the work signalled a shift of direction. Visage echoed a trait apparent in earlier shows by numerous artists recently where small works and assorted media have began to take hold.

In Visage, Julian Hooper’s haunting portraits whose subjects of flower/figures morphed still life and portraiture into one. Michelle Hanlin’s metamorphosis took another form as it punned Dali-esque and shadow puppets for a psychological portrayal. Colour, abstraction and a shift in scale gave the show its edgy-ness.

Julian Hooper’s show at Gallery 9 last year comprised works originally created for the frames belonging to a NZ regional gallery that he filled with his strange vegetal personages. At Gallery 9 they were shown devoid of the collection’s frames and placed in a different series of frames creating a kind of additional absence. The show served as a good example of an interesting concern that has been appearing in many recent exhibitions – a focus that taps into subject matter that might best be described as ‘stretching across time’. This suggestion seems to be being made by a number of different artists in a variety of ways and deals not only with quotation or appropriation but also with a disruption of the idea of a pictorial continuity or a seamless surface; replacing it instead with absence often seen as gaps in the picture plane that are both literal and metaphorical.

Jess MacNeil’s work does this conceptually as well as actually by removing the figures but leaving their trace as they transverse their urban landscapes. This was demonstrated in her powerful show at Gallery Barry Keldoulis in March that bought together her video works and her painting in a synergistic coalescence of matter, medium and immateriality. Sean Rafferty’s Ghost Mountain at Mop in January traced a link between memory and recall of both the filmic and the real. Rafferty used cardboard, graphite and film to play off nostalgia burning it instead into the viewer’s mind as an after image rather than a recollection. And so it goes that the nature of viewing work is also about recalling absent work, it’s serendipity is our part in the process but beyond this comes hindsight – the lynchpin for generally acknowledged agreement. It is very easy to digress into a round up of the high lights every notable show and maybe that’s the clincher for why this sort of retrospection is usually anchored to a specific artist’s work and not discussed in such meandering terms.

Ben Cauhci, The Start of It All, 2009.

Ambrotype.

And with that in mind it was in fact two quite specific shows that have been doing the haunting for me – The New Victorians (University of Sydney Art Gallery curated by Louise Tegart in 2008) and A Fragile State (Martin Browne – curated by Matt Glenn in January 2009) Even the some of materials read like a list of ritual ingredients for some spell or hex- hair, bone, wax, ink and air -in both exhibitions.

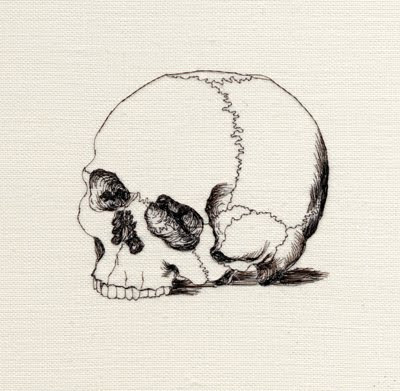

The New Victorians was a great little show (little only in terms of the space and great in so far as the work went): the Sydney University Gallery is a small space and in true Victorian style it quite a tight hang. Ben Cauchi’s ambrotypes – one off photographic plates – captured the spookiness of an age where the spiritual loomed large. Liyen Chong use of her own hair to embroider pieces served as a memento mori both implied and actual. Chong’s work reappeared in Matt Glenn’s A Fragile State.

Liyen Chong, I don’t know who I am but I know who I might be, 2008.

Hair embroidered on linen, 32x37cm.

A Fragile State was a marvellous wake up call. It asked us to consider not only the act of viewing and the materiality of the work but suggested a parallel thread between the experiential and the actual, the seen and the unseen as if these aspects of the art works could stand in for that lived experience. Roh Singh drilled holes in sheets of the perspex to make solid forms appear from thin air. Built up with layers of clear acrylic sheets the image was sandwiched as though it were both fixed and yet suspended, caught in the moment between one movement and the next, like a single a heart beat that divides life and death. Stuart Fleming’s mesmerising ink dot painting suggested the possibilities of phenomenology where colour takes on both the form and the idea and we are aware of another kind of perception of it. Charles Karubian and Leslie Rice’s paintings seemed to share a kind of ambiguity as if the figures in their paintings were being reabsorbed into their dark backgrounds. Destabilising the idea of painting as able to suspend time and space they too took on a fleeting quality. In various ways and to varying degrees each of the artists in the exhibition demanded some kind of reassessment of our experience of the artwork.

Isobel Johnston, August 2009