From Joanna Mendelssohn…

The Director of the 53rd Venice Biennale, Director Daniel Birnbaum, says that the title Making Worlds ‘expresses my wish to emphasize the process of creation’. The problem is that for the most part this process seems to be that of assembling flat-pack furniture. The over all impression of the official exhibition is of art with so few boundaries that it is completely interchangeable, and indeed its component parts often appear to be the same as they cross both nationalities and generations.

If this seems a bit harsh, then consider this. Liam Gillick from the UK, has his solo gig at the German Pavillion where he has constructed a giant raw timber modular kitchen, complete with stuffed cat. The kitchen is based on the Frankfurter Küche (Frankfurt Kitchen), the original modular kitchen designed in 1926 by the Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky.

Liam Gillick, How Are You Going To Behave?

A Kitchen Cat Speaks for the German Pavillion, 2009

Germany is well represented in the Palazzo with Wolfgang Tillmans’ essentially decorative metallically hued exploration of colour in photography . Meanwhile the Nordic countries, working under the supervision of the artistic duo Elmgreen and Dragset have combined in the Norwegian and Danish pavilions, both critiquing the supposed surface splendour of over-designed lives.

In the politest way, the 24 artists involved in these projects have blown a huge raspberry at the art collecting class. The Danish pavilion has been transformed into an investigation into a dysfunctional family, via the fictional agents “Vigilante Real Estate” who propose to sell this discordant home via leaflets and a tour by a frightening ‘agent’.The culture that brought the world Ikea is now deconstructing what those over-designed lives might be. Meanwhile, at the Norwegian pavilion, they present a ‘crime scene’ where one of the over-designed, over-considered collectors of modern art and modern people has been ‘murdered’. It is a harsh assessment of the very class which travels to consume events such as the Venice Biennale.

Col Tempo, The W. project

Péter Forgács’s installation

As always the national pavilions are a mixed bunch. Some of them are relentlessly dreary, self-important and over indulgent. But there are some high points. Roman Ondak at the Slovak Pavilion is a breath of fresh air. His installation has been to create a garden, where nature reclaims the art. This is the place to recover from the harsh assessments of Péter Forgács in the Hungarian Pavilion. Col Tempo takes actual footage of the Nazi experiments into human body types (and an interview with a survivor) and links it to portraits. The 60 year old Forgács layers his art with family memories of the Holocaust and personal memories of life under the Soviets in this acknowledgment of human evil. In a nod to its colonial reach, Dutch Pavilion has been given to the Indonesian born Fiona Tan has created Disorient, an ironic video installation contrasting opulence and poverty in modern Indonesia, with a voice over narrative from the voyages of Marco Polo. Is another case of cross cultural transfer. In this context Shaun Gladwell’s MADDESTMAXIMVS is both raw and polished; a bit like the movie Legally Blonde where Reese Witherspoon goes to the law students’ party dressed as a Playboy bunny.

The very slick presentations of the Giardini are contrasted in the Arsenale, which is on the whole a disappointment as components of old ideas are recycled again. This is where visitors go to see the new, the cutting edge, yet the high point is a 2002 installation by Lygia Pape, the Brazilian artist who died in 2004.

Sometimes however this can be fun as with the Barcelona duo, Bestué/ Vives, whose 2005 Acciones en el Universo (Actions in the Universe) shows a series of often hilarious surrealist installations in an apartment. In the midst of this one of the artists appears to be stuck across the corridor, heavily made up as ‘Old Bruce Nauman’. This is more than appropriate as the US has exerted a great deal of marketing effort to ensure that the aging conceptualist is the ‘star’ of this year’s Biennale. He is not, but a great deal of fluorescence has been recreated in his name. Bestué/ Vives video also includes a riff on Ikea furniture, which returns to the central theme.

The best part of this Biennale is not to be found inside either the Giardini or the Arsenale, but in the many exhibitions scattered throughout the city. This is the context for Once Removed (curator Felicity Fenner; artists Vernon Ah Kee, Ken Yonetani, Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro) at the Ludoteca.

As well as the freshness and strength of these installations, the actual placing of the exhibition is brilliant. It is on the path that leads out of the Arsenale so the jaded visitor coming from that seriously disappointing exhibition walks into its unpretentious open door and is bowled over by Claire Healy & Sean Cordeiro’s huge monument to video cassette culture. This is followed in the second room by Vernon Ah Kee’s assertion of surfing as a part of Aboriginal resurgence and completed with Ken Yonetani’s magical sugar corals.

Other pavilions are not found so easily. Steppes of Dreamers, the Ukraine’s great evocation of mysterious desolation is well worth the effort of searching though the confusing alleyways of Venice, especially as the upper floor of the Palazzo Papadopoli presents a mysterious and threatening narrative . The project curator Wladimir Klitschko, stresses his career as a boxer in his official biography, and also in the poster at the Academia. Two of the three artists (Illya Chichkan, Ogata Kinichi and Mihara Yasuhiro) are from Japan. It’s good to see nationalism in retreat.

Sheza Dawood, Triple Negation Chandeliers (White, Blue, Pink), 2008

Neon on aluminium frame, 190×220 cm.

There is a sense here in Venice of the age of empires in both wax and wane. This is especially so in East-West Divan, a collaborative effort from the heartland of the former Persian Empire: Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. This is a hard one to find, upstairs from Lithuania, more or less north-west from the railway station. It is however one of the more rewarding experiences. Khosrow Hassanzadeh has paintings based on ordinary women who fit the US description of ‘terrorist’ by virtue of their nationality and religion. Shezad Dawood presents a triple chandelier proclaiming the central tenet of faith ‘There is no God, but God’ in fluoresent light, Muhammad Imran Qureshi presents Moderate Enlightenment, miniatures for the modern world. Farzana Wahidy’s photographs of Afghanistan are able to concentrate on people in more intimate way than the standard sensationalized work of western photojournalists.

The other surprise national exhibition is far easier to locate as it is on the main tourist drag between the railway station and San Marco. Ragnar Kjartansson’s installation for Iceland is called The End. There is a glorious chutzpah to this presentation, and it is no surprise to discover that staff from other pavilions regularly cruise by on their days off. In a darkened room a standard four wall screen projection shows the artist and another playing folk music, filmed in the Canadian Rockies. In terms of interest this is about the same as the Canadian pavilion (ie pretty dull). The visitor then goes to another room where an open door shows the (real) Grand Canal flooding a studio with Venetian light while the artist (from the video) paints a young male model. This exercise will be repeated for six months. A stack of beer bottles indicates the main form of refreshment, and there is a strong sense that people from Iceland really appreciate Italian summer weather.

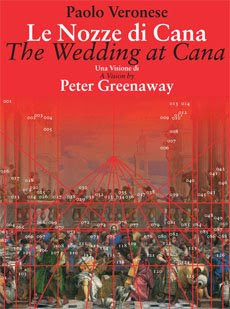

Oddly enough the best contemporary art exhibit on view in Venice has nothing to do with the Biennale, except for the timing. On the island of Palladio’s San Giorgio Maggiore, Peter Greenaway has directed a tribute, an exposition of Veronese’s Wedding at Cana and is proof, if ever any were wanted, that great art can be nourished by art of the past, and that there is no essential conflict between the creative tools of our age and those used throughout history. The site is the refectory of the Monastery which was the original home of the painting before Napoleon plundered it for the Louvre. Greenaway’s meditation on this work is played over a full size reproduction where figures are highlighted, music played conversations created, and visual relationships analysed.

I am not sure that it is worth the long flight just to visit Venice for the Biennale, but this work alone, with its layers of meaning, and all surrounding beauty is well worth the jet lag.