The Art Life’s editor Andrew Frost was invited to take part in a PechaKucha nite hosted by Super Deluxe at Artspace. With a brief that stated “talk about anything you like” Frost spoke on the work of author Philip K. Dick. The format of PechaKucha asks that speakers prepare 20 images that are screened for 30 seconds each and that their talks fits the time limit. What follows is an edited version of Frost’s presentation…

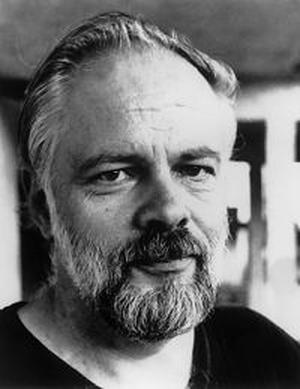

Philip Kindred Dick was born December 16th, 1928. He was the author of 44 science fiction novels and 121 short stories. He died March 2nd 1982 aged 54. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle was first published in 1962. I read it when I was a teenager in the late 1970s and – like many things you discover when you’re a teenager – the book had an enormous effect on me.

The novel is an alternative history set in an America under the joint rule of the Nazis and Imperial Japan. Its characters illuminate the differences between our world and this other place – a Japanese trade delegate in San Francisco unknowingly collects fake antiques of the American West; the antiques trader is manufacturing fake antiques; a bored housewife has an affair with an undercover Nazi agent. The agent is searching for a science fiction writer who has written a seditious alternative history postulating a world in which the Americans had won World War 2.

Dick’s theme of shifting realities is a staple of meta-fictional cinema – beginning in 1982 when Blade Runner was made from Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – and then through all the adaptations of Dick’s stories that have been turned into so-so Hollywood action films, then to the work of Charlie Kaufman to Fight Club, Cypher and Stranger Than Fiction. In these movies sci-fi looks less like the future and more like the now, or the recent now of the just past.

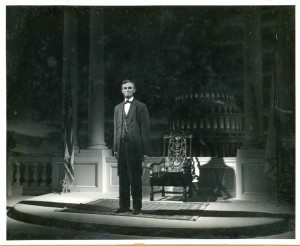

In 1991 Jean Baudrillard speculated on the future of science fiction: “Perhaps the SF of the era of hyperreality will only be able to attempt to “artificially” resurrect the “historical” worlds of the past, trying to reconstruct in vitro and down to its tiniest details the various episodes of bygone days: events, persons, defunct ideologies-all now empty of meaning and of their original essence, but hypnotic with retrospective truth.”

One of Dick’s recurring fictional set pieces is a moment when the reality of a story is revealed to be a simulacrum, in danger of collapse, a moment of revelation where the characters – and the reader – are reminded of the tenuous connections between fiction and truth. In The Man in the High Castle one character, sitting on a park bench, has a vision of San Francisco as it really was in 1962. He is nauseated by the bustle and high rise of the modern city, retreating back into the fictional world with its horrors and exterminations and Nazis moon landing, finding within it something more comforting in its falseness, or as Baudrillard put it, a hypnotic retrospective truth.

This moment in fiction anticipated an event in Dick’s own later life when it was revealed in a mystical vision that Southern California was a chimerical overlay in time – beneath the highways and strip malls and tract housing of Orange County Imperial Rome existed in parallel with our current time. Dick speculated that the world we see is a hologramatic illusion maintained by an alien satellite in orbit around Earth, a Vast Active Living Intelligence System, or VALIS for short.

Science fiction is a series of literalised metaphors that remind you that the world we take for granted is as much the creation of a consensual system of beliefs, ideologies and suppositions as it is due to any hard-wired external reality. With Dick’s work – and The Man in The High Castle in particular – you realize that the you reading these words, or the you listening, is another character dreading the moment when the camera dollies back to reveal the stage set upon which this drama is being played out.

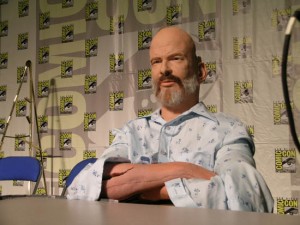

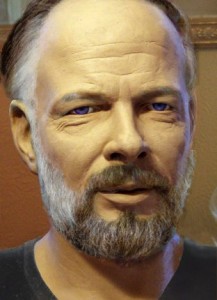

Perhaps you will become aware that this taken-for-granted world is a simulation and you’ll somehow rebel, or perhaps you simply won’t be aware that – posthumously – you are an animatronic programmed to respond coherently to the questions of interviewers and gawkers alike, speaking in snippets of recordings of your own voice.