How does one begin to decide whether massive, thematically curated exhibitions like the Biennale of Sydney are successful? Step one – stop being so literal minded, argues Andrew Frost.

For many the experience of large-scale exhibitions mounted by museums, public galleries and the hundreds of biennales that dot the globe is defined as a task of interpreting curatorial intention. Since these exhibitions can feature hundreds of individual artworks by hundreds more artists, the road-signage of the curator is considered the crucial difference between a coherent experience and a confusing, seemingly bewildering array of contemporary art.

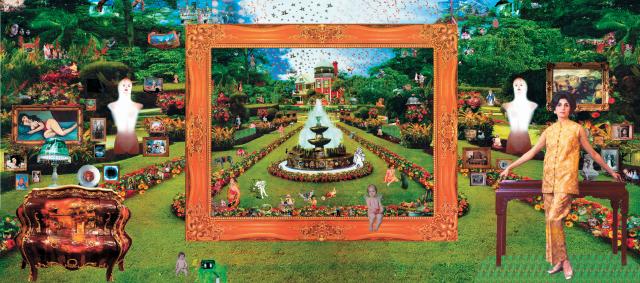

Lara Baladi, Perfumes & Bazaar, the Garden of Allah, 2006.

Visual montage; print and light box, 248 x 560 cm.

The tendency of audiences confronted with a mega-show is to seek some defining meaning within the curator’s intentions rather to treat them as a do-it-yourself walk-through. And this tendency is understandable since the scale of most biennales is demanding. The Biennale of Sydney [BOS] has seven venues [one of them occupying an entire island], a book-sized catalogue and publicity bumpf that promote its title on every flag pole in town… At this kind of scale, there has to be some sort of rational reason for its existence, no?

The default position of mainstream critics is to treat the Biennale as a failed model. Certainly, the Biennale-style theme based exhibition and the sort of work that is routinely included within them highlights the absurdity of art that is dependent on corporate and government sponsorship but which seeks to have some sort of critical dialogue with contemporary society. BOS2010 artistic director David Elliott’s claim that the current BOS is dedicated to the very people of the world who cannot see it – those mired in poverty – is just one aspect of the uncomfortable relationship between the ‘critical dialogue’ of ‘first world art’ and the seemingly insoluble iniquities of globalisation. While Elliott’s declaration has more to do with a sense of solidarity with folk cultures than the idea that the BOS somehow helps the oppressed peoples of the Earth [which it certainly doesn’t in any practical way], this will to inclusiveness underscores the political tenor of much contemporary art.

But for many critics of the old media it isn’t just that this will to inclusiveness is a failure, it’s that the art itself is illegitimate. Without wanting to [once again] trudge down the track of justifying video art, installation, photography or any of those other allegedly indefensible forms of art making, let us just say that there is a high-walled cultural divide between those who think video art et al is a nonsense and those who simply accept them as a part of contemporary practice. For the moment it is the conservative side of the divide that gets all the media space. This is part of the reason that, despite all the money poured into the BOS, all the good intentions of its participating artists, and those in Sydney’s art community who in principle support the BOS, there is an unavoidable sense of defensiveness within the ranks.

The Biennale of Sydney has since 2000 been more of a hit than a miss. Sydney 2000 broke the thematic approach by surveying the then current work of past BOS participants and was organised not by a single curator but by a “curatorium” including the late Nick Waterlow. In 2002 Richard Grayson curated The World May Be [Fantastic] along highly personal, weirdly idiosyncratic lines. The show was perhaps the most tightly curated BOS produced since the 1990s with a maddening repetition of formal approaches that, despite everything, was both highly entertaining and probably the last word on ficto-historical art making. It also happened to include one of the best art works I’ve ever seen – Mike Nelson’s Reptile House.

Isabel Carlos’s On Reason & Emotion in 2004 and Charles Merewether’s Zones of Contact in 2006 have both been retrospectively consigned to the bin of bad ideas and failed attempts. Carlos argued that there was no need to over-think the theme of her BOS as one could just as easily feel the emotion in the work, whereas Merewether’s conceptual grandiosity amounted to much the same thing – no memorable art works at all. Ok – the Antony Gormley installation of thousands of tiny fired clay figurines was memorable but anything I can recall from the Carlos show were for the wrong reasons: lady with her head in a basket? Cheese with Band Aids? Ergh.

Carolyn Christov-Barkargiev’s Revolutions – Forms That Turn in 2008 inaugurated Cockatoo Island as the main venue for the BOS. It was perhaps for that reason that the 2008 outing claimed a new level of popularity among casual gallery visitors with record attendances – free entry plus a pleasant ferry ride on the harbour makes for a great day out regardless of the qualities of the art on display. But Christov-Barkargiev curatorial gambit was a refreshingly straightforward approach to curating the show, devising a theme that included both formal and politically interrogative riffs on the notion of ‘revolution’. [It also had something that many other incarnations of the BOS have attempted but failed to produce – the show stopper. Whatever BOS17 can muster it won’t in all likelihood match the hugeness of Pierre Huyghe‘s Forest of Line, the 24-hour installation inside the Sydney Opera House]. That many in Sydney got so het up over Christov-Barkargiev’s inclusion of museum pieces from the collections of the Art Gallery of NSW and the Museum of Contemporary Art spoke more to the inexperience of those critics than it did with international exhibitions where that kind of thing is standard practice.

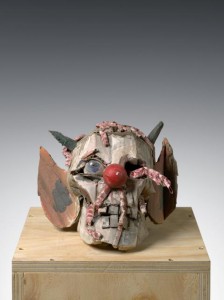

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Migraine, 2009.

Cardboard, paste board, newspaper, glue, polystyrene, posterpaint, 20x24x24cm

Copyright © the artists Photo: Jochen Littkeman

Courtesy White Cube, London and Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin.

And so to Elliott’s The Beauty of Distance: Songs of Survival in a Precarious Age. As far as thematic framing is concerned, BOS17 appears to be supported by elaborate and baffling intellectual scaffolding that operates quite independently of whatever the art in the show happens to be about. As the curator of massively ambitious shows in Europe and Japan, Elliott is no stranger to the construction of huge shows with sprawling historical overviews and contemporary and historical works. In terms of its theme, BOS17 is somewhat reminiscent of Robert Storr’s 2007 Venice Biennale Think With The Senses: Feel With The Mind which attempted to create a similar snapshot of a troubled political climate, but Elliott’s show has a far more crafty, haptic vibe than Storr’s extravaganza. But this sense of apparent bafflement has as much to do with a refusal to engage as it has to do with the intentions of the curator.

Thematic organisation in large exhibitions tends to be hugely problematic since there is always a bell curve of relevance – at one end you find work that is completely relevant, then moving through a middle section of “sort of relevant” to the far end of “possibly relevant if considered in a certain way.” Looking back over the history of the BOS you find that the more successful exhibitions have been the ones that struck a delicate balance between curatorial intention and the works of art, neither overloading the intended reading of the show nor leaving the audience perplexed or confused. Many treat the curation of Biennales as a kind of accident, as if it were an afterthought rather than what they are – authored experiences ordered in very precise ways. The sprawling physical state of the show matches the lasso of the ideas. If the Biennale of Sydney were as “tightly curated” as some seem to argue for, then it would be massively tedious – a hopelessly didactic experience that gives neither art works nor audience a chance to breathe – or think.

It’s for this reason that Elliott’s approach to BOS17 marks it out as one of the more successful outings of recent years. Elliott’s approach has been to highlight the act of anthologising itself, purloining Harry Smith’s legendary Folkways compilation for its post-colonic subtitle, and letting the associations begin where they may. That is not to say that the catalogue does not offer a number of starting points, incorporating as it does texts by Michel Focault, Jeremy Bentham, Jean le Rond D’Alembert, Arthur Schopenhauer – and Bob Dylan. The catalogue isn’t a grab bag of spurious justifications, but rather a primer for how one might begin to interpret the show across its various venues. Where the “beauty of distance” has an inescapable parochial association, Elliott proposes Schopenhauer’s interpretation of the Romantic sublime instead, finding within the friction of associations something that proposes a third reading. Like the anthology, it’s the montage of associations and approaches to making art – and positioning it in the show – that reveals the intention. The catalogue design itself harks back to the late 19h and early 20th century compendiums of knowledge such as encyclopedias or mail order catalogues, a graphic tradition artist Chris Ware mined so successfully, and which remains an unacknowledged debt by BOS17 designer Daniel Streat. But as a visual cue to the BOS17’s intentions, the catalogue is on a par with Rene Block‘s Readymade Boomerang.

The complaints about the BOS and the inevitable defensiveness of its supporters have a lot to do with the intellectual tradition of the Biennale and the willful refusal of conservative critics to engage with it on its own terms. If the BOS can be accused of anything it is that it doesn’t buck the trend of international art shows by abandoning the thematic approach for the survey show, or conversely, narrowing the curatorial idea down to one easily digestible thought – say “painting today”.

Elliott’s show is a superb model of the discursive approach to making a massive show like the BOS accessible – here are some ideas, here are things I like, now go forth and see what you think. The average punter isn’t even required to do any reading beyond the title of the show – it lives as a thought that can be considered against the experience of looking at the art itself. In these days of audio tours and extensive wall texts, of guided tours and literal minded critics, the delight of finding out for yourself is considered too demanding for most gallery goers. If it isn’t laid out for them most punters are simply too lazy to do any of the hard work. My own rule of thumb with the BOS – or any large show for that matter – is to look at the work first and then make up my mind as to whether a] the theme relates to the experience, and b] if there are any works that I like. If those things connect, then the Biennale is successful. Based only on that formula BOS17 is already above average.

Now this is the reason for reading TAL. Perceptive analysis of the art and the curatorial project, with an elegant tinge of malice towards the unnamed evils that lurk on the pages of the braodsheets.

Pingback: Tweets that mention BOS2010: Themes and Damned Themes | -- Topsy.com