Luise Guest considers presence and abscence in Gao Ping’s latest exhibition…

As I drove through Surry Hills on my way to meet Chinese artist Gao Ping, I looked in my rear-view mirror and glimpsed a girl at a bus stop who could have stepped out of one of the artist’s delicate ink paintings. Wearing a chiffon dress with boots, hunched against the cold wind and talking into her mobile phone, she seemed at once frail yet fierce, reminding me of the tiny figures that populate Gao Ping’s works on paper. These tiny figures are placed very deliberately into large areas of empty space, conveying a sense of loneliness, disconnection and absence. In conversation over coffee the softly spoken artist agrees that her work is a little like a diary. She stores up memories of the people and things she observes in her daily life, until she is safely in the solitude of the studio when they spring back to life under her brush – a weary figure leaning sideways on a park bench, a feisty girl in jeans talking on a mobile, a gathering of men in suits. Together with her characteristic subjects of sad, abandoned toys, and collections of chairs, lamps or electric fans, they suggest a whole population in a state of flux. The delicate restraint of her ink marks gives them a sense of impermanence, as if they could dissolve, shape-shift, or transform themselves into something else altogether. It is perhaps not surprising that the artist describes her experience of living in the constantly changing chaos of Beijing as one of loss and sadness. There is humour too, however, to be found in her wry observations of the unexpected details of city life.

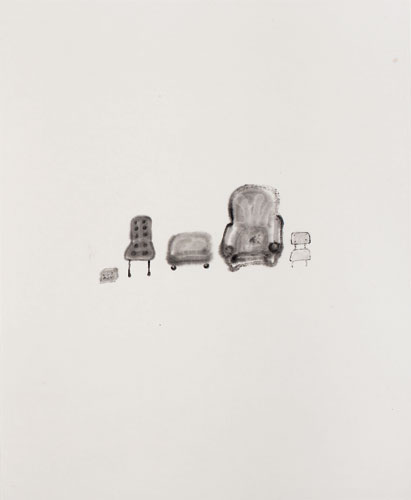

Gao Ping, Still Life – Chairs, 2011, Chinese ink on rice paper, 45 x 36 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, Stella Downer Fine Art and China Art Projects.

Born in 1974 in Shandong Province, and trained in the art powerhouse of the Oil Painting Department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, she now combines her painting practice (works she characterises in her conversation with me as ‘strong’) with her delicate ink on paper works, inspired by the traditions of the Song and Ming Dynasty masters. Four ink paintings are currently showing in The Drawing Room at Stella Downer Fine Art, and more will be shown in the Maitland Regional Gallery in Paperworks, a show curated by gallery director Joel Eisenberg. http://mrag.org.au/exhibitions/coming-exhibitions/ Gao Ping sees her oil on canvas works as her response to the ‘outer world’ of the city. Earlier paintings represented the destruction and rebuilding of Beijing – she has previously described the expansion of the city as “a monster” – depicting cranes, scaffolding, construction sites and traffic. Recent works respond to the unease created by this endless transformation in a new way, through the depiction of imaginary landscapes which represent a harmonious retreat from the chaos of contemporary life. In contrast, the ink paintings seen here in Sydney respond to a fragile inner world of feeling and memory.

A paradox lies at the heart of Gao Ping’s practice: the longer you look at works which initially seem frail, delicate, even tentative, with their tiny figures or domestic objects floating in a vast emptiness, the more emotive weight they attain. They deserve the long look, and repay you for it with a growing sense of stillness, and an awareness of how beautifully observed they are. The artist herself embodies that same contrast. Although gentle and quiet, her seriousness of purpose, inner strength and confidence in her practice is evident. It is tempting to connect her works with those of the 17th century female painters in China who recorded intimate details of daily life, an ‘inner world’ of women. We talk briefly about artists who have worked primarily with ink on paper, and she is intrigued to discover Joy Hester, another artist who translated her own life into a quick, sure use of line and mark to speak of a woman’s experience of the world.

Gao Ping most admires Ming Dynasty ink painters such as Ba Da, whose landscapes achieve that much sought after balance between stillness, space and closely observed detail. She finds his work both sad and “calm in heart”, a lovely phrase which could equally apply to her own work. For Chinese artists, she says, the traditions of ink painting are “like the ground under your feet”. In Gao Ping’s hands this tradition has developed into something edgy and contemporary – her work speaks of our experience of living in a fluid world where little is permanent and people as well as objects can be disposable. Her understanding of Chinese traditional painting is evident in the way she places her tiny figures and floating forms into a white emptiness in dynamic relationships both to each other and to the space within which they are contained. She also loves the work of Antony Gormley and one can see a similar aesthetic response to figures in relationship to the spaces they inhabit in Gao’s work.

The Drawing Room juxtaposes four ink on paper works by Gao Ping with works by Lao Dan, another Chinese artist who is both working within and reinventing the conventions of ink painting. His scribbly calligraphic line is reminiscent of the Abstract Expressionist painter Mark Tobey, making me think about the important dialogues between eastern and western art, waxing and waning over long periods of time. The threads linking artists across time and across continents are complex linear forms, much like many of the pieces in this show.

Gao Ping, ‘Still Life – Girls’, 2011, Chinese ink on rice paper, 45 x 36 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, Stella Downer Fine Art and China Art Projects.

The works of the two Chinese artists are hung with drawings by Australian artists such as David Fairbairn, Viola Dominello, Rae Bolotin and Ambrose Reisch. This juxtaposition of diverse practices and traditions works surprisingly well, underlining the liveliness and inventiveness of contemporary drawing practice and also creating interesting points of connection. It is interesting in this context to see the drawings of sculptor Rae Bolotin. In works such as Night the Maker of Deceits her sinuous looping line also evokes ink calligraphy. David Fairbairn’s very beautiful studies based on his observations of works by European masters such as Grunewald, Goya and Rembrandt are a reminder of the important place of drawing in both eastern and western traditions. In amongst the dark, dramatic drawings of Fairbairn and the moody charcoal chiaroscuro of Ambrose Reisch, the sense of weightlessness and of the fragility of human connections in Gao Ping’s work provides a counterpoint – a very different sensibility and a most distinctive artistic voice.

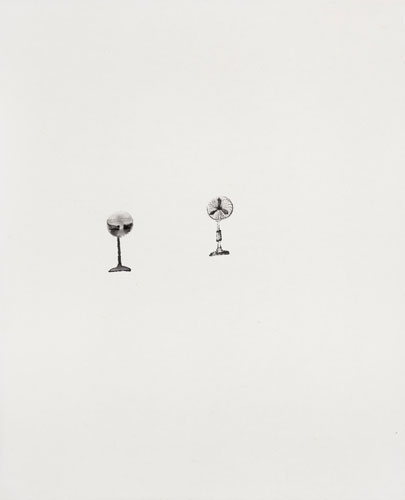

Gao Ping, ‘Still Life – Fans’, 2011, Chinese ink on rice paper, 45 x 36 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist, Stella Downer Fine Art and China Art Projects.

Tiny things are sometimes more important than the large and obvious, she says, and indeed in the four works in ‘The Drawing Room’, these “tiny things” – four slightly sagging wonky chairs and a footstool lined up in a row like a family portrait, 2 electric fans, a solitary figure – suggest they are part of an ongoing narrative. In ‘Still Life – Girls’, each of the 4 minute figures possesses their own undeniable sense of self, from the overtly sexy figure in black stockings, the exhausted one lying slumped flat on her back, to the two whose softly blurred outlines turn away from us. I wonder aloud if all these works, both those containing human figures and those focused on inanimate objects, are in some way a representation of the artist herself, an on-going self- portrait series. She laughs, but does not deny it.