Luise Guest reports live from Beijing on the paintings of Jing Yuan Huang…

Jing Yuan Huang is in some ways a hybrid being. Her atypical Chinese story helps to explain the piercing clarity of her observations of the homeland to which she has returned, which makes viewing her paintings an uncomfortable, as well as an intriguing, experience. When we met at her studio in Beijing as she prepared her November exhibition of paintings, ‘I Am Your Agency’, she explained why she works in a particularly idiosyncratic way, and how her figurative paintings differ from those of artists trained in the Chinese art academies.

Jing Yuan Huang I AM YOUR AGENCY, 2013, Oil on Canvas, 50 x 80cm image courtesy the artist

Born in 1979 in Guangxi, she grew up in China with a father who is a traditional ink painter; so far, so normal for a Chinese contemporary artist, many of whom emerge from families in which image-making and artistic expression are the norm. Her choice to study not art, but tourism, at university may have been her first divergence from an expected path. Her discovery that the fanatically nationalistic response of her teachers and fellow students to the US bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade made her “uncomfortable” was the first sign that she may not be best suited to the career path she had chosen. Veering wildly from the norm, Huang travelled to North America to study art, completing a BFA at Concordia University Montreal, and then her MFA at the renowned School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

This experience, as well as many years of living away from China in the United States, has given her a unique perspective which she now applies to creating works which represent contemporary China in all its contradictory complexity. An early work, ‘Transmigrating Inadequacy’ was comprised of site specific murals and architectural elements which she created from Xerox-printed enlargements of digital scans of photographs of original drawings. The notion of the authentic power of the original is questioned; and she explores ideas about the validity of reproduction and simulation, particularly potent in China where anything and everything can be, and often is, faked. In these works we see Huang’s fascination with the reproduced image – a Walter Benjamin-inspired meditation on the original and the shadow, the real and the liminal. From her position as an outsider, a diasporic immigrant to North America, she observed with some detachment the way in which identity is attached to place. Theories of liminality, and the creation of a space which was “neither this nor that”, using techniques which were themselves neither painting nor photography, allowed her to examine the experiences of immigration and dislocation.

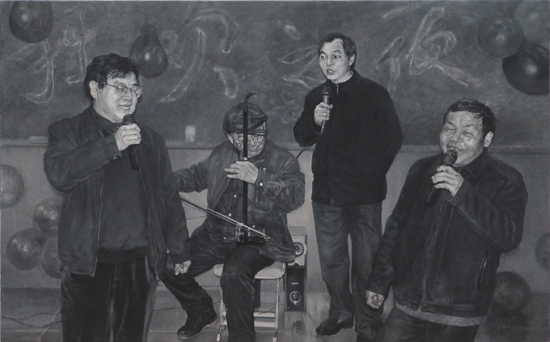

Later, her ‘Gossip from Confucius City’ series, part of an ongoing conceptual project in which she created a fictitious institute and its museum, furthered her project of examining the way in which China presents itself to the world. Inspired not by the philosopher, but by the state-sponsored Confucius Institute, an arm of Chinese soft diplomacy with which many international students of Mandarin will be very familiar, she created a series of paintings which look like black and white photographs. On closer inspection they are revealed to be surreal fictions in which characters act out ambiguous narratives against a Chinese mise-en-scene. In this series of paintings, which are represented in the collection of Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, she painstakingly copied her own small collages in a very small format with intense rendering and high realism. Again there is a conscious and deliberate process of distancing – not unlike the way in which images are filtered, manipulated, copied, shared via social media, and recombined again and again in our image-saturated world. The paradox is that the painted version appears hyper-real yet we know it is a fictional world, a parallel universe of androgynous hybrid western and Chinese creatures, movie stars operating in a constructed reality.

Earlier versions of this work include collages which evoke the spirit of dada and, in particular, Hannah Hoch: they emerge from the same imperative of satirising dominant social structures. Huang is particularly interested in the way in which China represents itself to the west. The artist told me that she chose the name for this series in 2011 when Ai Weiwei was arrested. “I think it’s more interesting to create a fake institution where you can manipulate and export culture and cultural artefacts.” She described this work as a “transitional project” in her shift from the United States back to living in China. “I am definitely someone very interested in the logic of how governments want to be seen and how individuals want to be seen,” she says.

Jing Yuan Huang in her studio, Beijing October 2013, photograph Luise Guest.

I suggest to her that from her complex position as both an outsider, looking in at her own culture, and an insider looking out to the world, she may be able to see China more clearly than artists who have never had this experience. She agrees, saying, “Now I can ground myself and have a critical mind about what is going on inside China. It can be perceived as a little bit postcolonial, (and) we are post post-colonial in many ways. That discourse offered lots of opportunities for art outside the canon to be seen, and to initiate a bigger sense of the contemporary world.” She aimed to create a surreal response to the way in which China promotes itself to the world, in ways which are hyper-inflated and hyperbolic. Any casual viewing of Chinese television will provide a sense that there is no spectacle considered too “over the top”. Hence the gaudy imagery in Jing Yuan Huang’s works, which combines traditional Chinese motifs – dragons, peacocks – with photographs of grand urban vistas, erotica and scenes of Hollywood excess.

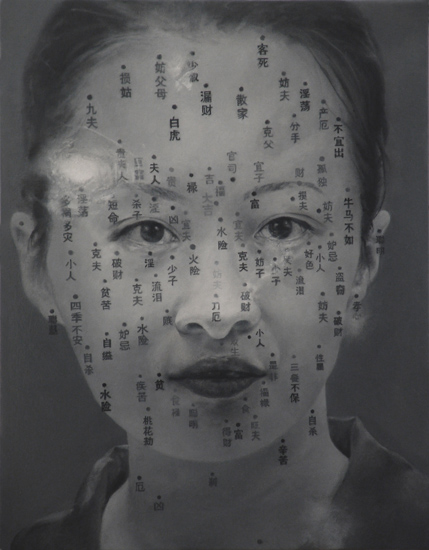

In her November exhibition at Force Gallery in the 798 Art District in Beijing entitled ‘I Am Your Agency’ she presented a series of monochrome, highly realist paintings which again are sourced entirely from photographic images. In this case, they are all based on banal photographs taken from Chinese web sites. The history of photography in China is problematic and unique. Photography was restricted from the 1950s until the end of the Cultural Revolution. It was controlled by the state, used for propaganda and social control. Only in recent years has photography become a highly significant expressive form for Chinese contemporary art, so dominated by painting in the 1990s and later, by conceptual and installation practices.

Jing Yuan Huang I Am Your Agency No 38 2013, Oil on Canvas, 45 x 60cm image courtesy the artist.

From tens of thousands of ordinary, badly composed and badly shot random images sourced from websites, Jing Yuan Huang has selected a small number to reproduce in paint. Her title asks us to consider who has the “agency” in the construction and viewing of these images. “I got to know lots of images from the internet – the accumulation of images from the last five years from vernacular photography,” she says. “Not from photographers. The photos are really bizarre, for example photos of an official from the Propaganda Bureau, taken as a compliment by his staff, or a snapshot of a chicken owned by somebody, or a shirt someone wants to sell on Taobao [Chinese e-bay] – it’s really a world that is banal and not totally legitimate – not an image you could project on the wall about Chinese people.” Of course these images in themselves are not negative representations of contemporary China. “You can’t see negative images online on Chinese websites, or using a Chinese search engine,” she says.

But somewhere in the transformation from photograph to painting, and then in the carefully considered juxtapositions of pairs and groups of images, subversive meanings emerge. The artist has paired snapshots with more “official” images to suggest readings which critique the ways in which the Chinese represent themselves, and how we all understand the world mediated through the shadow imagery of photography. It also represents Huang’s own “continuing struggle to disengage from the authority of state media” (Gordon Laurin, ‘Documenting Photography: New Painting by Jing Yuan Huang’ 2013) One can link this back to her experience as a young student, when the university teachers exhorted the students to demonstrate on the streets against the US, hiring a bus to take them there, and whipping up such anti-American fever that one teacher, too afraid to stay, went to the US Embassy for protection. In our conversation about this time, she simply said, “I didn’t want to do that – (use) my individual body to support something in a big angry group. So I just stayed in my dormitory. But after that I was on their blacklist or something and then it confirmed for me that I was not comfortable with what was going on.”

Jing Yuan Huang I Am Your Agency No 22, 2013, Oil on Canvas, 73 x 107.5cm image courtesy the artist.

Individual works in the series, such as the empty rows of fabric-skirted chairs, in ‘I Am Your Agency No. 38’ suggest many possible readings, and one cannot help trying to construct a narrative to make sense of the image. Is the wedding banquet cancelled? Is the official party abandoned? Has something terrible happened here? In fact, the artist tells me, she found the original photographic image on a badly designed website page advertising chairs available to be hired for functions. The actual meaning of the image is so prosaic, so mundane, that it denies our appetite for drama. Other images similarly suggest multiple readings, which in many cases will be undermined by the prosaic reality of advertising photography, or the tools of propaganda. Like the ‘Da Zi Bao’ (‘Big Character Posters’) of the Cultural Revolution, which at first boldly denounced class enemies, revisionists and landlords, and then descended into gossipy accusations of infidelity and ‘fornication’, photography has descended from the high realm of visual ‘truth’ to the banal, the digitally manipulated and the tacky sales pitch. China is, after all, the country where provincial authorities routinely doctor photographs for political propaganda purposes, inviting the derision of internet commentators for their hopelessly inadequate and frequently hilariously bad Photoshop skills.

‘I Am Your Agency No.22’, taken from a photograph depicting blind ballroom dancers, utilises an impressive command of chiaroscuro to evoke both pathos and dignity in the intense concentration of the sightless faces of the dancers. The beautifully rendered folds of the white shirtsleeve against the deep blackness of the woman’s dress and the way the figures emerge from a velvety darkness signify their momentary pleasure in a world of difficulty. The work is not easy to look at but it suggests both trust and closeness. It is juxtaposed with a painting taken from a news photograph of political leaders, seated next to each other but looking away. The work is awkwardly revealing, as snapshots of politicians in unguarded moments so often are.

Jing Yuan Huang I Am Your Agency no 20 2013, oil on canvas, 50 x 39cm image courtesy the artist.

‘I Am Your Agency No. 34’ depicts an awkwardly cropped female face, eyes averted from the camera, and part of another figure in an interior space, undefined but for the structure of a window. Like other works in the series it reveals Huang’s determined effort to avoid ‘correcting’ and refining the poorly composed photographs which are the source of her images. She occasionally removes an extraneous detail or further crops an image; however, she prefers to work with the compositional infelicities of non-professional photography, believing that they are intensely revealing. In her artist’s statement for the exhibition catalogue, Huang refers to the ways in which people become “casualties of their own image-in-the-making and their image production is reduced to a self-imposed performance.” In our conversation in her studio, surrounded by these unfinished paintings in the month before the exhibition, we discussed the ways in which people now act as ‘curators’ of their own image, particularly through the use of social media. In China, this is particularly poignant when one considers the dramatic changes that have taken place in society. On the wall of her parents’ bedroom, she says, is a photo taken in 1979 in southern China. “They stand side by side like well-prepared soldiers trying to impress their leaders…I can detect an intimacy that comes from their shared experience as casualties of war.”

One might ask, “Why undertake this laborious and time-consuming process of rendering ‘throw-away’ ephemeral photographs in paint?” The answer lies in the very meticulousness of the artist’s hand, as she works layers of scumbled glazes to create an illusory solidity and reality of form. Rather than scrolling quickly past image after image on a screen, we are forced to stop and really look, to consider what images mean, and what they tell us about ourselves.