Luise Guest on on Reformation at White Rabbit Gallery…

If you go along to the White Rabbit Gallery expecting Chinese contemporary art to consist of Pop-inspired Mao imagery or Cultural Revolution horror, you are in for quite a surprise. The new exhibition, the gallery’s tenth, is “Reformation”, which my dictionary defines as “the act or process of improving something or someone by removing or correcting faults, or problems.” In a Chinese context there are some dark connotations here – people with inconvenient opinions may find themselves sent away to be “reformed” in deeply unpleasant ways, for example. However, what we see in many works in this show is post “reform and opening” China in all its infuriatingly contradictory complexity, its joyfully creative inventiveness, and its manic energy. Optimism and confidence; urban decay and reconstruction; business deals and the 21st century language of globalisation; sex and commerce; the role of religious belief; and the courage to speak uncomfortable truths: all these are here. But so too is an appreciation of the fragile beauty of nature, the humour and pathos of desire, and the malleability of language.

Madein Company, Play 201301, 2013, genuine and artificial leather, BDSM accessories, foam, metal, wood 545 (L) x 300 (W) x 330cm (H) image courtesy White Rabbit Gallery.

Eminent Chinese artist Xu Bing, speaking about his “Phoenix” project – two monumental suspended birds made from Beijing construction site debris, currently installed in the nave of Manhattan’s St John the Divine Cathedral – said, “China is an incredibly experimental place. China’s methods, its momentum, and its vitality, all these things – no-one in the world understands. Not even the Chinese.” (http://vimeo.com/64178206 ) It is precisely this hyper-drive vitality, fast-forward momentum and restless creativity that is revealed once again at White Rabbit. More than 50 new works, together with a number of old favourites from Judith Nielson’s impressive collection, create a narrative that has much to tell us about contemporary China.

The first thing you see is a dramatic “salon hang” of 37 paintings from the collection, a visual feast hanging ceiling to (almost) floor in the atrium. Wang Luyan’s Global Watch is a giant’s timepiece bearing the flags of China, the United States, Iran, Korea and other nations in a wry comment on the inevitability of global conflict. Above this hangs a 2006 work by his wife, Qin Fengling, Red, with her characteristic technique of tiny sculpted figures covering the entire surface, referencing submerging of individual desires to the collective, the overwhelming mass of the Chinese population. Lu Xinjian’s City DNA Beijing, part of a larger series representing numerous world cities, emerges from an examination of aerial views from Google Earth, revealing the sameness of the contemporary urban hub. A seemingly flat pictorial space, and a surface that appears to be an impenetrable code, or a diagrammatic representation of a flickering electrical charge, on closer examination reveals some of the distinguishing features of each singular place. In this work, the grid of Beijing, with the Forbidden City at its central meridian, merges into an incoherent jumble like every other place in the developed and developing world. Mondrian’s Modernist grid has become the language with which to expose the homogenising impact of globalisation.

Shi Zhiying, High Seas, 2008, oil on canvas, 200 x 800, shown here in an earlier exhibition at White Rabbit, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

As an antidote to works exploring the stresses and strains of the contemporary world, Shi Zhiying’s glorious monochrome ocean vastness, her sea sutra, evokes the sublime, a meditation upon Buddhist notions of emptiness. Ma Yanling’s delicate portraits of Shanghai actresses of the 1930s, including Jiang Qing (Madam Mao) reveal her interest in the hidden history of women in China. Other works are more personal. Bingyi’s I Watch Myself Dying, painted after the artist suffered an appalling accident resulting in serious burns and multiple surgeries, is a compelling, raw work which reveals her interest in European painters such as the Symbolist Odilon Redon as well as Chinese ink painting masters. Bingyi described her painting practice to me as “Intensely primal. It raises questions about our fundamental being – what is pain, what is suffering, what is loneliness?”

Strangely, this visual tapestry of paintings is not incoherent. Somehow it is still possible to appreciate each individual painting, just as on a Beijing street, amongst the kamikaze traffic and advertising signage one can still notice the ancient surface of the hutong doorway, or the birdcage hanging on the power-lines. It’s a clever way to incorporate old favourites from the collection in an exhibition that presents so much that is completely new.

Shyu Ruey-Shiann (Taiwan) Eight Drunken Immortals, 2012, metal, wheels, wires, ink, motors, transformers, sensors 480 (L) x 240 (W) x 250cm (H) image courtesy White Rabbit Gallery.

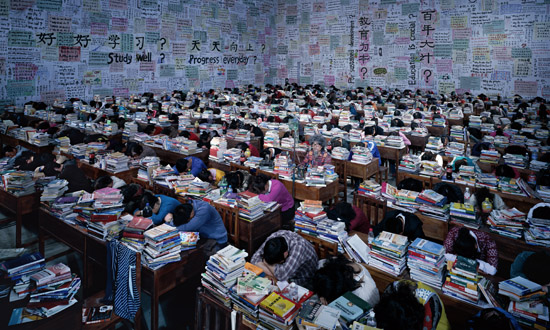

On the first floor there is great humour in Shyu Ruey-Shiann’s Eight Drunken Immortals, a set of small, busy robots zooming about erratically on shopping trolley wheels, inspired by the apparently intoxicated moves of certain martial arts disciplines, and the Taoist story of the immortals who defeated their enemies in unarmed combat whilst staggering about as if drunk. As they move around the floor they “draw” with ink on sheets of paper, in an entertaining parody of the art of calligraphy. In contrast to the whimsical nature of these drunken immortals, powerful works on this level including Wang Zhiyuan’s Close to the Warm, an installation of Chinese characters on tiny strips of paper attached to the wall, swarming like little insects around an incandescent light bulb. It’s a reflection on the malleability of meaning and the ways in which language can be distorted and corrupted by authority, and a far cry from Wang’s huge fibreglass pink knickers in the previous show, although both works have something to say about the state of the contemporary world. Wang Qingsong’s enormous staged photograph Follow You is the kind of HSC exam nightmare that haunts the dreams of many of us well into adulthood. Hundreds of students sit at tiny desks behind stacks of textbooks in both Chinese and English, the walls of the vast space papered with Mao-era quotations exhorting hard work and study – “Progress Every Day!” They are all fast asleep, as if a spell has been cast over the entire nation. In the centre the artist sits, wearing a fake grey beard and long hair like an ancient scholar, the only figure awake in the slumbering masses. Then we realise it is because he is connected to an IV line, hooked up to goodness knows what stimulant. Wang Qingsong specialises in large-scale ambitious allegories, commenting on the most pressing issues facing contemporary China. Here, he makes a wry comment about the factory assembly-line that is the education system, a grind of rote-learning with no incentive for independent thought, a highly stressful “gaokao” examination at the end of the line, and the very real prospect of unemployment unless you have family connections – the all-important “good guanxi”.

He Yunchang’s One Metre of Democracy is a challenge for audiences. Not for the fainthearted, the video records surgery carried out (without anaesthesia) on the artist – a metre-long cut from his shoulder to his knee. He asked 25 “voters” to make a democratic decision about whether he should go ahead with this bloody and painful event. They are photographed with the artist before and afterwards, looking decidedly less carefree in the latter images. In previous works this artist has cast himself inside concrete for 24 hours, and has had a rib surgically removed and made into a piece of jewellery with the addition of 400 grams of gold. This kind of ‘endurance’ performance emerged in China in the late 1980s and 1990s as artists explored new freedoms and responded to artworld events such as the Sensation Exhibition. Damien Hirst has a lot to answer for, some might say. In “Performance Art in China” Thomas Berghuis proposes that Chinese performance artists have “acted out” their art, often in opposition to the principles governing correct behaviour in the public domain. The use of the artist’s own body, sometimes in extreme ways, has numerous precedents, from the ‘Fuck Off’ exhibition in 2000 to the work of Ma Liuming and Zhang Huan. In a Chinese context in which artists are reflecting on bitter and tragic events, ‘endurance performance’ practice such as this has a particularity and resonance that it lacks in other contexts. It was after all a young Mao Zedong who said, “In order to civilize the mind one must first make savage the body.” (Although performance art was probably not exactly what Mao had in mind.)

Wang Qingsong, ‘Follow You’, 2013, C-print, 180 x 300cm, image courtesy White Rabbit Gallery.

MadeIn Company’s Play 201301 is a Gothic cathedral, all flying buttresses and gargoyles, squeezed into black leather and zippers like an architectural Madam Lash, suspended from the ceiling by bondage ropes. The challenge posed for audiences by “the artist formerly known as Xu Zhen” (now reinvented as a corporation rather than an individual) is the myriad interpretations that can be applied to works which emerge from a setting not unlike Warhol’s “Factory”. Reminiscent of Brook Andrew’s Wiradjuri zig-zag patterned jumping castles, the work is at once playful and deeply sinister, and is already proving a big attraction for audiences at the gallery. Faith tethered to the earthly realm by human desire? Spiritual elevation corrupted? Perhaps the work is about religion as yet another “brand” in the modern world, another marker of identity and tribe. However one may interpret this work its physical presence is undeniable – it seems to hover above the floor as if the ropes are holding it down rather than supporting it, as if it might float away, defying gravity like Magritte’s Castle of the Pyrenees.

Huang Jingyuan, ‘I Am Your Agency No 22’ 2013, oil on canvas, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

I last saw Huang Jingyuan’s paintings in Beijing, in the artist’s studio and later, in her solo show in the 798 art district. Her series I Am Your Agency, five of which are shown here next to her earlier series Gossip from Confucius City, reflects her interest in the role of photography as an instrument of both social control and self-actualisation. She creates her meticulous oil paintings by selecting random amateur photographs from websites – a plate of somebody’s dumplings, a cheesy photograph of a government official, a still from a movie, an advertisement for chairs, somebody else’s chicken. Random, poorly composed, these vernacular photographs provide a rich source of images which can be juxtaposed to create new and surprising meanings, satirising Chinese society no less than an artist such as Wang Qingsong. “I am definitely someone very interested in the logic of how governments want to be seen and how individuals want to be seen,” she told me. Another painter of great technical virtuosity with a unique approach to adapting western painting conventions is Dong Yuan. We have seen her paintings of her entire apartment, with each object on a single small canvas, at White Rabbit in previous shows. This time she is represented by Repeated Illusion, a series of works on canvas inspired by old master paintings. Repeated Illusion Number 1, for example is the vase of a 17th century still life painting, in all its trompe l’oeil hyper-realism. The flowers have been removed, however, and they hang pegged whimsically on a line above, flat cut-outs which entirely defeat the intention of the original and add a quirky humour to the weight of the western canon. When we spoke at her studio in Beijing in late 2012, Dong Yuan told me that when she was studying at the Central Academy of Fine Arts she became obsessed by the skills of old master painting, including the tiny, incidental details in the backgrounds of such works, always painted with extraordinary clarity and precision. She felt that these Renaissance and 17th century paintings elevated the mundane to something of great significance. Beside her painted vase in this show, instead of the cut flowers and fruits of the traditional still life, a tiny seed is sprouting.

Another work which speaks powerfully of “reform” is a large, almost white painting by Zhou Zixi, Dawn – Light Fog 09. At first it seems to be an abstract work, perhaps a reference to Malevich, or to Rauschenberg’s “white” series – after all his 1985 exhibition in Beijing was one of the most significant in the history of contemporary art in China. Look more closely and it begins to look familiar. Recognisable shapes emerge from the mist. The iconic vista of Tiananmen Square is slowly revealed, shrouded in fog. For a moment you wonder if it is a reference to the terrible air pollution which has left the streets of the capital in a Dickensian gloom. Then you see the rows of tanks. It’s about the way in which recent history has been “reformed”. Erased, wiped away. The artist wants the events of June 4 1989, at which he himself was present, remembered. I recommend standing in front of this work for a while – for me it is the highlight of the exhibition.

A lyrical video work by Yi Lian, Undercurrent, Is likewise strangely compelling. A young child sleepwalks through a night landscape. Water in brooks and ponds flows rhythmically, eddying around rocks, rippling over stones, inhabited by foraging ducks and turtles. Small, cold-looking naked children lie half submerged in shallow water running over pebbles. The sound of the water creates a trance-like state in the viewer. Suddenly the camera shifts and we see a row of men, roped together, eyes closed, stumbling through the darkness. They enter the water and are quickly submerged. In another sequence they float – fast – downstream, their white shirts billowing under the water. In fact, the young child is the artist’s nephew, who sleepwalks regularly. But perhaps, beyond any literal reading, sleepwalking is a metaphor for living in today’s China. The world you see when you wake is not the world you knew when you fell asleep. Everything is different, and continually changing, in ways that alter everything and challenge every assumption. What dream is this? Every billboard on every construction site in Beijing proclaims, “This is my Chinese dream.”

Reformation runs at White Rabbit Gallery until August 3.