Luise Guest meets Thomas Sauvin and discovers that 650,000 discarded pictures tell a story…

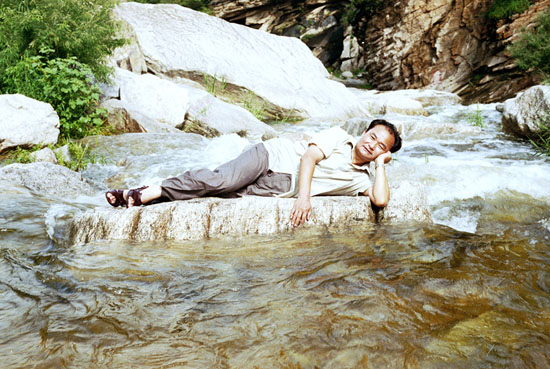

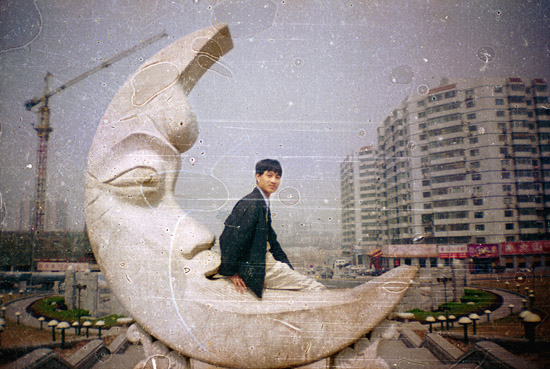

Thomas Sauvin is a rescuer of lost images. From more than 650,000 abandoned photographic negatives he has assembled an archive which tells a previously untold story – the story of China in the years from 1985, when photography first became accessible to ordinary people, to about 2005 when analogue photography was superseded by digital technologies. Badly shot, poorly lit photographs, often printed from damaged negatives, these are in many ways mundane images of ordinary people doing ordinary things. They joyfully show off their new consumer goods; go to theme parks, or to the beach; travel; enjoy time with their families and go to MacDonald’s. Yet these apparently banal images represent perhaps the most dramatic social change of the 20th century. Showing at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art in an event associated with Sydney’s Chinese New Year celebrations, these still images, installations and video provide the viewer with a compelling narrative and a most unusual art gallery experience.

Sauvin does not describe himself as an artist. Rather, he says, he is a collector and curator who presents his collection in the manner of an artist. Like an archaeologist exploring a midden of Kodak moments, he has ‘mined’ discarded rolls of film destined for the silver recovery process in order to reveal a China that may surprise western audiences. Beijing Silvermine emerged from Sauvin’s experience of working with the UK-based ‘Archive of Modern Conflict’, a privately funded collection of vernacular photographs and perhaps the largest collection of images in the world that shows history through the eyes of ordinary people. Over time, however, he became more interested in seeking out negatives and starting his own collection of Chinese photographs. Just a small part of this extraordinary accumulation – an alternative history – is here in the gallery. The time these images represent is the period of opening up and reform; the first moments of Deng Xiaoping’s oft-quoted “To get rich is glorious” cultural shift; the starting point of the entrepreneurial and fast-changing China that we know today. Large numbers of people were beginning to accumulate a little more wealth. They had enough to buy household appliances such as refrigerators (which feature in a surprising number of photographs), to take holidays, and even to travel abroad. China moved from an emphasis on the collective towards a new determination by ordinary people to pursue individual happiness. And with increasing access to affordable photography they now had the means to document their lives.

If you expect Mao suits and bicycles, or apocalyptic pollution, you will be surprised – these images bear little relation to what western audiences might expect from Chinese photographs. Sauvin, who has lived in Beijing for many years, is irritated by what he sees as the “extreme” reactions of foreigners to China. He says, “Either they love China and see it in a ‘Tai Chi in the park, mystical mountains’ Orientalist manner, or they hate it and all they can see is ‘pollution, corruption, destruction, Ai Weiwei, Tibet.’ And that’s it.” In contrast the collection from which the twenty-eight images showing in ‘Beijing Silvermine’ are drawn reveal ordinary people living their lives during an extraordinary time of transformation. The photographs range from the banal, to the beautiful, to the bizarre. Sauvin finds recurring themes as he sifts through thousands of negatives, which he buys by weight from a recycling centre. He was immediately struck by the universality of experience, and he hopes that audiences here, as they have elsewhere, will recognise something of their own personal histories in the images he has selected for the exhibition. Some of the badly shot, luridly coloured snaps of people wearing truly hideous 1980s fashions could well have emerged from my own embarrassing family photograph albums. The time and place may be unique, but the themes are universal, Sauvin says – birth, family, leisure, travel, pride, joy, and consumerism. I remembered my snapshot of myself with my first car, shot in a suburban Sydney street, and agreed.

In this iteration of Beijing Silvermine a small selection of images, printed in a range of sizes, are displayed on one wall. Simple black frames evoke the way that photographs might be displayed in a domestic setting. We see leisure time at the beach, raucous family gatherings around restaurant tables, awkward poses in front of scenic monuments, and loving images of small children, images of travel, and women posing beside their new refrigerators (often in pride of place in the living area, and used as a surface on which to display other objects of significance.) The travel shots are especially fascinating, starting with people posing in Chinese theme parks (very odd indeed) and then later at the seaside, and finally overseas, frequently in Thailand. The same locations feature in many photographs. Tiananmen Square, and the same parks, gardens, lakes and fake waterfall are seen multiple times in the photographs of different people. These repetitions, seen in the animation, ‘Recycling’, created in collaboration with multi-media animation artist, Lei Lei, provide a sense of context and continuity – we have a sense of the bigger picture of a society in flux, beyond the experience of the individual.

A pile of creased and crumpled photographic prints in one corner of the gallery, a small mountain of discarded images in which are embedded monitors showing the video, suggests that ‘Beijing Silvermine’ is as much about the alchemical magic of film itself as about the subjects depicted in the photographs. I imagined I could still smell the vinegary traces of developer and fixer. Negative sleeves on a light table invite audiences to pore over them, much in the way that Sauvin and his assistant spend many hours intently looking, selecting, scanning and digitising particular moments from the random memories contained in each roll of film. A vitrine contains five albums designed by Sauvin each containing twenty prints and published by AMC Books in limited editions, including ‘Blue Album: TVs and Fridges’, ‘Yellow Album: Leisure and Work’, ‘Orange Album: Marilyn and Ronald’. (That’s Marilyn Monroe and Ronald McDonald, an indication of mass participation in western popular culture and the consumption of glamorous and exciting new products like fast food.)

I spoke with Sauvin at the gallery, and found him to be absolutely passionate about the significance of vernacular photography and this particular Chinese project – he talked for well over an hour without appearing to draw breath. He has a keen sense of the absurd, and, it has to be said, a very charming French accent. I asked him, firstly, to tell me about the way that ‘Beijing Silvermine’ began. Having studied and worked in China for a number of years, he met the director of the Archive of Modern Conflict at the Lianzhou Photo Festival, where he was then working, and began to assist that organisation with their collection of contemporary Chinese photography. For many years the AMC had focused on the experience of war through the images of ordinary people:

“They have always been interested in exploring the way that a certain type of image fits with a historical event…how authentic vernacular material could challenge the collective memory and how we represent it. Then at some point they started to collect material that was not directly related to conflict…I started working for them and collecting the works they were pointing out, and trying to make a digital data base which grew like a tree, with one branch leading to another. I did this for three years. At some point before 2009 I started to look at other things like postcards, botanical research, scientific material, family albums. A lot of photo books as well – from 1949 to the 1970s a lot of important photo books were published in China. I discovered that I really liked dealing with the photographs without dealing with photographers!”

“So what were the actual mechanics of beginning this enormous accumulation of images?” I ask. “…I decided to focus on negatives, you can scan them and it gives you more freedom. It’s more like a rescue. I started searching online in the simplest way possible, I went on Baidu and typed in “collecting negatives”, “negatives to sell” and I found this one guy, Xiao Ma, who was always leaving messages on people’s blogs asking them to contact him if they had negatives to sell. So instead of a seller I found a buyer. I was a bit depressed to think I was not the first one to have this genius idea, but I contacted him and discovered that he was not a collector but a recycler, interested in the silver nitrate. I went to see him and found this warehouse full of X- rays and CDs and all sorts of trash that contains silver nitrate, including a big pile of negatives. That first time I think I got a 50-kilo bag. I always buy by weight. It’s very good because I think the price is very cheap and he thinks the price is very expensive. So we are both very happy, me because I have so many negatives and him because he has fooled a foreigner. So it’s a win win!” Sauvin came to an arrangement with Xiao Ma, that he would purchase as many negatives as the recycler could source for him. Now, though, he says, it’s nearly over. “Given the quantity I think within six months or one year it will be meaningless. The idea is to stop the project when it is meaningless so it reflects the death of analogue photography in China.”

The history of photography in China is complex and problematic, used primarily as a tool of propaganda from 1949 to 1976. I ask Sauvin what he thinks is the significance of his huge collection of images. “I think it depicts a period of time that is hardly documented by anyone,” he says. “The period it covers is 1985 to 2005. The Cultural Revolution ends in 1976 and you have those ten years when the country is in chaos, the ideology is in chaos, and the understanding and practice of photojournalism is not mature. You don’t have a picture of the country and the way it was… From 1983, ’84, ‘85 you started to have very significant photographic artists, like Han Lei, Mo Yi, Lu Nan, shooting subjects like mental hospitals, tension in the streets, portraits of the countryside full of tension. Contemporary photographers really like to focus on pain, on problems, on tension, on anger.” In a revealing aside, Sauvin tells me that at the same time as Beijing Silvermine was showing in Hong Kong last year there was a major retrospective Chinese photography exhibition, curated by Rong Rong, at Blindspot Gallery. The photographers represented in ‘New Framework: Chinese Avant-garde Photography 1980s – 90s’ focused, says Sauvin, on “anger, tension, dysfunction. I was having my exhibition at the exact same time with photos curated from a million images and all I could find was humour, joy, loving parents with loving babies, travel, a bit more wealthiness… it was a very different thing.” Similarly to foreigners – outsiders with a distorted view of China – he thinks that contemporary artists are “the outsiders within the inside. They are Chinese but they are outside the society and they focus on painful matters. And then you have the insiders, just living their lives and starting to have moments when they feel they are happy. I am not being a fool and saying everyone had a marvellous life in China in the 1980s and ‘90s. But when they had these moments they could take a camera and document them. And that’s the face of China.”

When I wondered aloud how Australian audiences might respond to images which seem at once familiar and unfamiliar, Sauvin said, “When I showed the photographs in Hong Kong the reaction was ‘Is this propaganda or is it criticism?’ And I think, ‘could it not be somewhere in between? Are those the only two possibilities?’ The reaction was quite shocking. In England people were very surprised. They were expecting something completely different… Through authentic vernacular material you give a portrait of a country that’s radically different from what is in people’s minds. When you think about it it’s very funny because I show these in China to friends and everybody says, ‘That’s banal, what’s interesting in that? It’s just us.’ So they think I am wasting my time collecting meaningless things. But as soon as I cross the border people say, ‘I have never seen that.’

Given that his enormous archive provides compelling evidence of dramatic social transformation, I wondered what were the most significant changes that he has observed in the photographs. “ So many of them,” says Sauvin. “Of course, wealthiness is something you can witness. Firstly through a pure photographic approach. The rolls from the mid ‘80s contained 36 pictures taken over a period of time. You see outfit changes, day and night, different places. It was costing some money. By the end of the ‘90s you see 36 photos taken in one hour.” Photographic practice – a small and particular kind of human behaviour – mirrors a bigger social change, from a sparing, frugal approach to conspicuous, careless consumption. Then, he says, you can observe significant social change in the subjects of the photographs, particularly through pictures of travel. “I see the same Thai pagoda, the same beach near Bangkok…I can begin to predict what I will see. And I am almost sure I will see a Thai guy with his head in a crocodile’s mouth because they all go to the same show.” Later, other even more exotic destinations appear in the photographs. “Probably the second travel destination is Paris, the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre. I have a series I really like of selfies next to the Mona Lisa. People having their photo taken standing in front of old master paintings using the flash, so you always see this burned dot on the painting… It always leads to the ugliest images you can possibly imagine, badly framed, someone standing, and the reflection on the painting. When you bring them all together it creates this very nice series of old master paintings destroyed by Chinese tourists.”

For me, apart from its fascination as a social document, and an interesting blurring of boundaries – is this art? Is it design? Is it anthropology? – there is an overwhelmingly melancholy sense of pathos, of time past, of youth flown. All snapshots are a kind of memento mori. Embedded in the emulsion of these photographic images are the hopes and dreams of people emerging from one way of life into a new one.

Beijing Silvermine

4 A Centre for Contemporaru Asian Art

Until February 22 2014

Images: Beijing Silvermine’ 2009 – 2013, courtesy Thomas Sauvin.