The Art Life’s George Shaw reports from New York City on the art of unbranding…

The last time I triggered the flash on my phone camera by accident inside an art gallery or museum was on a recent visit to MoMA. Before the blaze of white light had time to fade to black, one of the invigilators had already started yelling at me. No short walk followed by a polite but firm request, not even a blistering death stare from afar – it was a screech across the room like what you’d expect from an embattled Under-10s footy coach. However, it didn’t come as a surprise, as there is no stroppier ‘invigimilitia’ than that at MoMA. I’ve had words with epauletted museum guards in the past, but at MoMA I know I’d be cruising for a bruising. So how to feel when reading a sign prominently displayed at the entrance to Hank Willis Thomas’ latest exhibition at the Jack Shainman Gallery actively promoting the use of flash photography? Especially when every work is photo-based? Hmm…

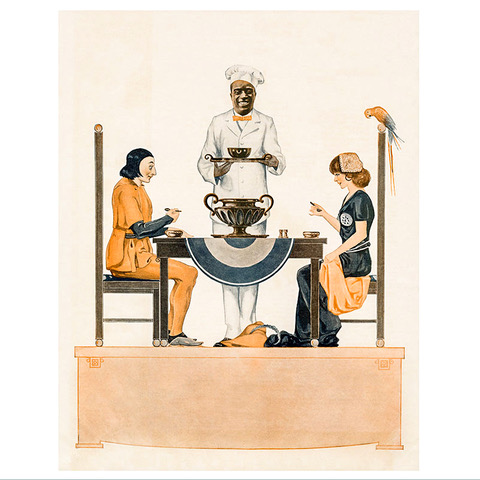

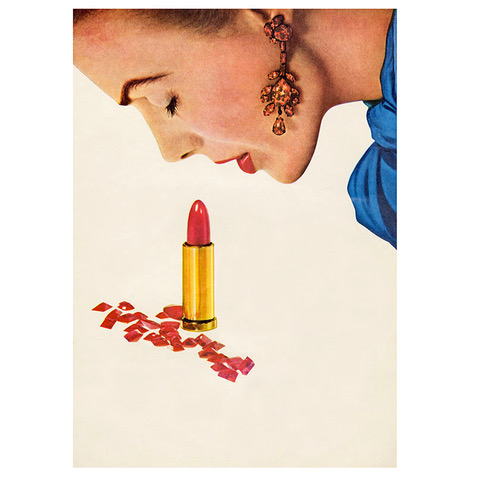

Thomas (b. 1976) is an American photomedia artist with an interest in identity, history, and popular culture. While in the past he has looked at how the black body is represented in visual culture, his practice is grounded on questions about privilege, inequality, oppression, and rebellion. I first saw his work in the series Unbranded: A Century of White Women, (1915-2015) when it showed concurrently across two Shainman galleries in 2015. As part of his process, Thomas manipulates appropriated images, not so much to re-contextualise as to reveal deeper meanings. For Unbranded, he used print advertisements that spanned a century of female depiction across a variety of product categories from furs, cars and lingerie, to air travel, kitchen gizmos, and pets. By excising all text and logos, the images were allowed to speak for themselves, all the patronising justifications for the overt displays of sexism and discrimination wiped off the page. The images, close to 100, were blown up large; tableaux after tableaux that produced an overbearing, cumulative heaviness. There was not a single a smile, but a hundred squints and winces forced instead.

Hank Willis Thomas, Unbranded A Century of White Women, 2015

Thomas’ ‘unbranding’ technique reframed artefacts of popular culture to discuss notions of beauty, virtue, power, and desire, as well as the systems that uphold them. The series looks at the spectrum of ideal feminine types that have been marketed across gender, racial, and socio-economic lines for a century. In today’s #metoo and #timesup cultural and political climate, the Unbranded series has particular resonance and relevance.

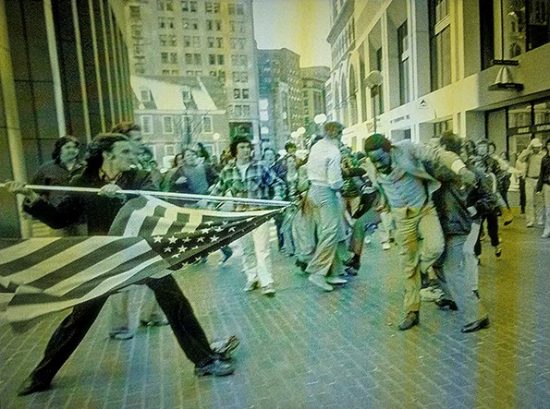

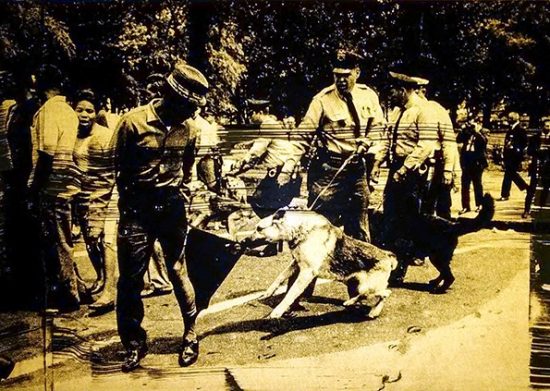

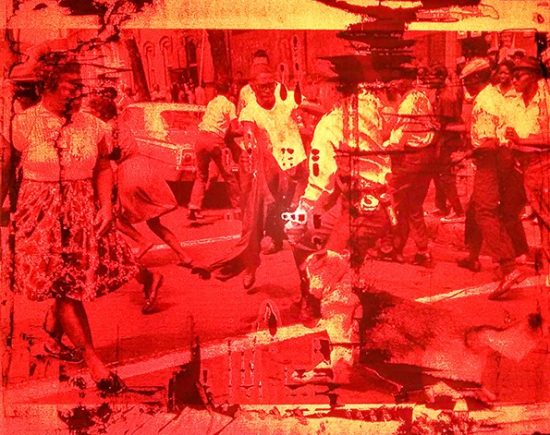

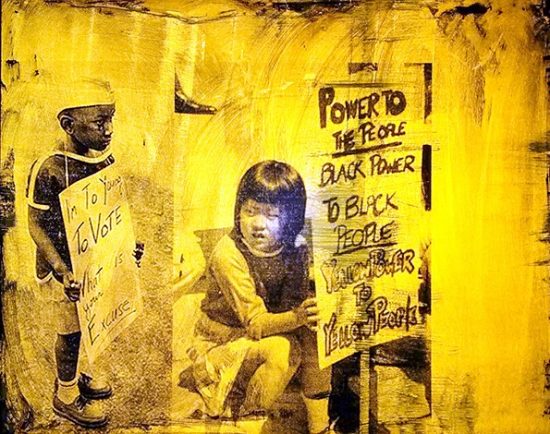

In Thomas’ new show, What We Ask Is Simple, images of past societal tumult in the United States, Europe, and Africa stand in for the unceasing battle for dignity, liberty, and equality. The transformation of these cultural and historical documents involved silvering, half-tone screen printing, and 3D image-capture, printed on retro-reflective surfaces and mirrors. The images printed on retro-reflective surfaces were covered either partly or entirely with various emulsions obscuring the subject. Approaching the wall, the individual works present themselves as large surfaces smeared enthusiastically AbEx-style with either white, red, yellow, or blue ‘paint.’ To overcome this viewing challenge, the sign by the front entrance to both gallery locations explains that “…the images need to be ‘activated’ by flashing light directly at them. Flash photography is therefore encouraged.”

Hank Willis Thomas, What We Ask Is Simple, 2018

On my first visit to the first cavernous, unlit gallery, the only thing I discovered was an empty pocket where my phone should have been. I was left completely in the dark. On my second visit, the images came to life but disappeared quickly, so that I had to either speed read the composition or look at it on my phone. There was nothing relaxed about moving around the room. However, Thomas has purposely created an environment in which there is a level of discomfort that goes some way to echo the narratives in the old news photos. Furthermore, the act of ‘photographing’ the work in order to see it suggests that he also wants us to take an active role by bearing witness to injustice, rather than stand passively in front of a history lesson.

Hank Willis Thomas, What We Ask Is Simple, 2018

On my third visit, I spent more time with the mirrored works. In each, the image is substantially covered by a mirror surface, allowing only one or two elements such as a target or a policeman hitting someone with a truncheon, to come through. Installed opposite white walls, the surface reflects a blank canvas against which the viewer finds himself or herself integrated into a moment in history, which is also a simultaneous space for personal reflection.

I have to confess an ambivalence about this series. While I am interested in and feel compelled by Thomas’ work and thinking, What We Ask Is Simple made me wonder why the word ‘gimmick’ kept echoing faintly in my head? The subject matter is historical and relevant to today’s cultural politics, and thanks to Thomas’ technical ingenuity it also packs a punch; so why the faint echo? I wonder if the conditions and specifications required to interact with the work as the artist intended, would mean that it would more likely reside in a museum. Or would the inherent degree-of-difficulty appeal to outre collectors with deep pockets? Who knows. Despite this perhaps needlessly mentioning my uncertain feelings, What We Ask Is Simple does have some flashes of brilliance.

PS All images shot with my crappy phone.