From Bonny Dot Cassidy

The last six months have blessed Sydney with exhilarating exhibitions of contemporary Indigenous art including the recently (and too promptly) ended Kitty Kantilla retrospective, plus two current shows: the Lockhart women’s group mounting at Hogarth Galleries, and a survey of the late Michael Riley’s photomedia work in Michael Riley: Sights Unseen at the Art Gallery of NSW [until April 27]. There is an intriguing dialectic of the local and abstractedly placeless in Riley’s oeuvre, highlighting that his is the first exhibition in Australia to focus on a south eastern Indigenous artist. In fact, this show gives the impression of a particularly delineated shift—from social documentary in the late seventies and eighties to conceptual aesthetics in the nineties—as if Riley had decided to take a great step away from his earlier profile. I come new to much of his art, including the film work showcased here, so that his development appears to be a step from one room to another but also, I feel, from striking work to banality.

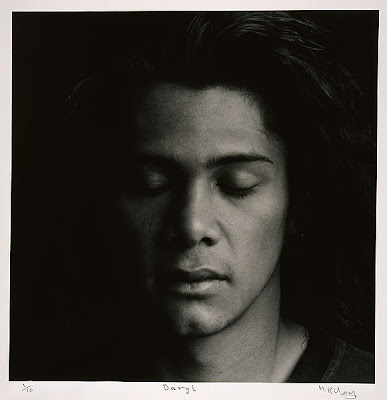

Michael Riley, Darrell, 1989/1990, from the series Portraits by a Window, 1990.

Gelatin silver photograph, vintage print. Courtesy National gallery of Australia.

© The Michael Riley Foundation

The spectre of the recently departed August Sander collection still lingers in the photo gallery. Those precise, intimate anthropological studies of German ‘types’, including a corner devoted to doomed outsiders, have been replaced by Riley’s large-scale, floating portraits of Indigenous Australians in full possession of the lens. Like Sander’s works, his photography focuses on individuals and the possibilities of monochrome. But here, there are no types; and Riley’s mastery of black and white seems almost perverse.

The stark studio backdrops of the Moree Murries and later Yarns from Talbragar Reserve series would be unforgiving, if not neutralised by the warmth of the subjects’ relaxed poses and presentation. These pictures give the impression of being much larger than their actual dimensions, partly generated by the halo effect that Riley creates around each body—levitating them within a kind of blaze, individuating neighbours, family and friends. This is particularly the case in the 1998 ‘Yarns’ portraits, which are mostly of single subjects. Riley’s earlier Moree and Dubbo shots embrace groups that appear to have assembled or been gathered as the moment dictated. Two fellow visitors walked the length of the series, naming each subject with familiarity, connecting up identities and anecdotes as if leafing through an album. Their appreciation of the portraits as people as well as pictures met face to face with the informal and celebratory nature of Riley’s compositions.

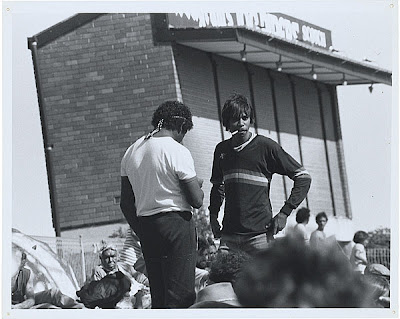

Michael Riley, The Knockout – supporters South Coast mob, from

Guwanyi: Stories from the Redfern Aboriginal Community c. 1975

Courtesy Museum of Sydney. © The Michael Riley Foundation

The confidence of his town profiles counterpoints the austerity of his mid-eighties portraits. These images of high-profile Indigenous Australians comprise some of Riley’s most legendary photographs. With his trademark crispness, and no matter how often they’ve been reproduced, the stunning Maria and Hetti shock and stimulate. For many viewers, the only photographs of solitary Indigenous subjects available for comparison would be found among the often-brutal clarity of colonial portraiture. As a white viewer confronted by Riley’s work, I find the sharpness of his line and tone fills me with new allusions, associations and affects. His images don’t erase or evade the memory of earlier ones, but their freshness and modernity looms over the past with what can only be called triumph.

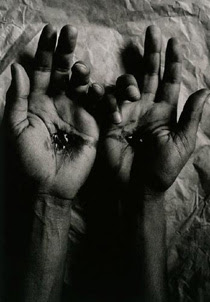

Michael Riley, Untitled 1992 from the series Sacrifice.

.Courtesy Art Gallery of NSW. © The Michael Riley Foundation

When colour does appear in his early works, it is often in shades of red, yellow and black woven through beanies, sweaters and scarves at Redfern Oval Knockout matches. Footy crowds are juxtaposed with street marches, both of them full of the easy smiles of little children. It’s disappointing, then, to find Riley’s dialogue with detail extinguished in the stylised, maximised series of the 1990s. Mission comprises elemental images of cracked earth, water surface and cloud configuration, while Sacrifice focuses on Christian iconography and shadows. These are some of Riley’s most richly tinted work—jewel green water, clear blue sky, rusty clay—yet they seem almost bleached of significance; while the loaded images of angels and crucifixes merely shrug off the responsibility of taking on more. Even if they fill an entire room, however, we must forgive any artist the furrows in a life’s work. Sander’s doomed specimens have been exorcised by Riley’s show, which hovers with some new spirit that’s loud and sunny, and alive.