Ian Houston writes from Sydney…

Neo Rauch’s Mazernacht.

I have seen the future of painting and his name is Neo Rauch.

The Art Gallery of NSW has recently hung two works by the East German painter Neo Rauch, Gebot and Mazernacht.

These two works caught my eye quite some time ago, but I dismissed them initially for what ever shallow prejudice that happened to be running through my embittered mind at the time. Yet they would not be ignored. Every time I have visited the gallery since, they have tugged at my eye, the flat colours, just back from gaudy, their muddied brilliance, disdainful of any obvious pleas for attention eventually seduce with their wilful obstinacy.

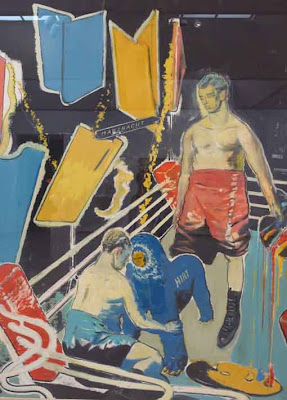

But it is the forms they take on the paper that truly captures your heart. What strange men and women inhabit this world? What beast is this, so loosely sketched, so bizarre in form and manner, with its human face and blue fur? Yet despite its ludicrous invention it insists that it be taken seriously, its depiction almost cursory, as if its existence were commonplace and need only be briefly alluded to. It stands there like a creature from a dream, appearing at every juncture, its melancholy face, sphinx-like, inferring the possibility of a secret knowledge, a codex for an impossible world. And on its side, its name, “Hirst” the stag. The creature stands on all fours in a boxing ring. A fighter sitting on his haunches grabs the creature’s front legs and stares at the ground as if contemplating some great truth that he’s been told.

Standing behind the creature is another boxer, who holds a painter’s palette, its colourful pigment dripping down to land on another palette that seems to be there by chance, though it seems ridiculous that that should be so. The boxer’s hands are ungloved though it seems as if the two have just been fighting. The ropes of the boxing ring closest to the viewer are broken and sheer toward the picture’s surface in abstract loops and skeins. Has the referee been ejected? Above the ring, folded sheets of colour drift in the wind whilst in the background arcs of paint stain the night sky and there amongst them is the word – “Marznacht”, the painting’s title.

Neo Rauch’s work seems always to be swollen with meaning and yet opaque and resistant to interpretation, his figures so complex, the allegories so arcane and personal as to confound the possibility of explanation. Yet it is this that makes them compelling, like the dream that one turns over in your mind as you move through the day puzzled as to its meaning but reluctant to let it drift away losing the beauty of its secret. I think it may be this possibility of meaning that has made his work so popular.

In an artworld as vast and diverse as the contemporary milieu it is ridiculous to make universal claims, yet there is some truth to the idea that “meaning” has become either the object of derision in the wake of Buren-styled nihilistic post modernism or else tied more directly to causes, or ideals (often curator driven). The notion that an artist, particularly a painter, should develop a language of imagery and iconography that is personal and in a certain regard consistently applied (figures such as the “Hirst” stag make regular appearances) seems old fashioned and yet Neo Rauch’s work is startlingly fresh. Perhaps the reason lies in the fact that he seems to have incorporated all of the ideologically driven discourse that has politicised the act of painting over the years and then incorporated it into the figurative play of his work. If the boxers in Marznacht have fought, then it was art that was at stake. His ouvre has such a sophisticated sense of the painting’s surface, of composition and colour that you cannot doubt the integrity of his thought. Just trace the manner in which the figures in Marznacht are rendered, the immediacy of paint and line and the way in which marks trail off from representation to expressive gesture. The work achieves a wholeness that is not just a matter of balance across the surface and the elements of the composition but an acknowledgement of the problem of painting itself.

And then there is the question of semiology. Rauch’s works are redolent with symbols, each figure seemingly standing in a careful relation with others as if they were part of a sentence. If the unconscious is structured as a language, then Rauch understands its grammar, elegantly mobilising a surreal sublimity that inveigles even as it confounds. Perhaps such talents arose in his time as a painter in East Germany. We have seen before the manner in which totalitarian governments tend to improve their artists, who, forced to rely on subtle gestures, heavy coding and the repression of revolt become adept at suggestion rather than statement. Rauch revel’s in this coded gesture, yet without the strictures of a despotic government to test, he has instead turned to his own identity, as if he were trying to find some outer limit of meaning, the creation of artworks whose worth is undeniable yet inexplicable. They are machines for implication, drawing your attention into a world of allusive play, suspending you above the ordinary dynamics of the work-a-day world and challenging you instead with your desire to understand the inexplicable.

Neo Rauch’s Gebot

Beside Marznacht, is Gebot, a later picture from 2002. Three men and a woman are in a room. One appears to be a labourer. He wears shorts and a blue singlet and stands on a square of turf that sits on the floor. A small tree grows from the turf; its leaves rendered as expressive squirts of red. In the labourer’s hands is a strawman or scarecrow whose head has been removed. Across from him a man stands behind a bench. He appears to be quite stern and in his left hand he brandishes the head of the strawman. In his right hand is a hammer. In front of him sits “the accussed”, his hands bound, his feet covered over with sacking as if he has just been released from a bag. To his side is a women. She touches his shoulder and shows him what could be a Stanley knife. The walls are decorated in a checkerboard fashion the centre panels of which seem to contain speech balloons. In the “speech balloon” directly behind the “judge”, there is the drawing of a jawbone. Just as with Marznacht, there is an immediacy in the imagery that seems to suggest that the allegory is in some way obvious, that demands you participate with these figures and try to understand this narrative. But just as with Duchamp’s bride stripped bare, meaning is constantly deferred, slipping away from you like the meaning of a dream.

It is interesting to think of these paintings as part of a German tradition that trace, in their absurd profundity and surreal meta criticism, a line through the actions of Beuys back to Grosz, Dix and even onto the late pessimism of the Blau Reiter’s post war paintings by Kirchner and Beckman. They are ultimately sad songs, paen’s to the loss of innocence but with no understanding of the crimes, like Kafka’s Mister K. A haunted visionary who tries to chase away sin only to find that the blood is on his own hands. You should see them before they go back to the warehouse. You never know, it might even make you want to paint again.