Never doubt the sincerity of an artist. Even when it seems like it might be a joke, a pisstake, some sort of ironic double play [indeed, especially when it seems so] there is nearly always a serious intent behind the effort. You can spot the fakers pretty easily – the people who get into the art world out of spite or a misguided sense of revenge. The odd thing is that in the three decades or so that we’ve been around the art world we can only think of two examples of fakers making it, and then their careers were so short lived it hardly made any difference.

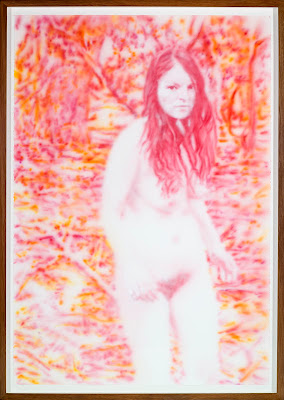

Del Kathryn Barton, You are what is most beautiful about me, a self portrait with Kell and Arella.

Which in a roundabout way brings us to the subject of the Archibald Prize for Portraiture. Since Del Kathryn Barton was awarded the $50,000 prize for her You are what is most beautiful about me, a self portrait with Kell and Arella just over a week ago there has been a lot of talk about why her painting won. The speculation has ranged from the usual talentless naysayers having a go at Barton for being successful, to a more considered reaction that claims – well, she might be an ok artist but the only way she could have won is her dealers working tirelessly behind the scenes pumping Barton career hype, lobbying the Art Gallery of NSW trustees or doing a deal with Satan. As far as we know, Barton aint never been down to the crossroads at midnight, and as for the dealer claims, there is absolutely no substantiated evidence that either Karen Woodbury or Vasili Kaliman had done anything more than a good dealer would do to support an artist.

The critical reaction, meanwhile, has been mixed. There have been some good overviews of the Prize. Joanna Mendelssohn brought an insiders insight to the history of the prize for a column on the ABC’s Unleashed site while Elizabeth Farrelly beat us to the punch with a comparison between the Archibald and exhibition of photos of chimps at the Australian Museum. John McDonald has had two goes at reviewing the Archibald in The Sydney Morning Herald, first as a news item and then as a full-blown review in last Saturday’s Spectrum. McDonald voiced a number of reactions that we’ve heard elsewhere about Barton’s painting – that it isn’t as good as her effort last year, that it’s decorative and that, despite its failings, it’s still the best thing in the line up of finalists. The Esteemed Critic’s claim in his news item that Barton’s family values are somehow akin to fashionable political stance are beneath contempt, being more emblematic of McD’s bitchy misanthropy than of a coherent understanding of where Barton is coming from. Say what you will about Barton’s painting, her sincerity is beyond doubt.

The dismissive description of Barton’s painting as decorative is more of a puzzler. For most people in the art world the decorative is regarded as a less serious visual vocabulary than the canonical gestures of, for example, abstraction or, the big trend in Archibald finalists this year, the school of impasto paint application. This is to profoundly misunderstand what being “decorative” actually means. To engage with it is as much a considered and active choice for an artist as any other approach to making paintings. All of Barton’s choices are conscious and aware of the social agency of those gestures. You don’t have to like ‘em, but you do have to respect them.

Finding anything else in the poor line up of finalists that comes close to Barton’s painting is a tough call. Our wish that Roger Borham’s Dad, what a smile might win was a faint hope. It’s such a small painting… and size matters. Hung next to Neil Evan’s Blue Days, Black Nights, another incy wincy picture done in the style of Bob Dylan, the hang favours a Lilliputian view of the world.

Alexander McKenzie, Sarah Blasko.

At the other end of the size and style spectrum is Alexander McKenzie’s portrait of Sarah Blasko. Like his landscape work, McKenzie’s picture is way out there on its own. The oddly balanced composition, the fine, detailed brushwork, that Dali-esque sky – McKenzie is in with a chance for future Archibald’s if he continues entering works as idiosyncratic as the Blasko portrait. Despite the fall off in quality of the finalists over the last few years it always seems the prize goes to someone prepared to take a chance and do something different [and which also spells doom for all those academic artists whose execution of a style is flawless but offers very little in the way of excitement].

Of the rest of the field of Archibald finalists there are only two others worth mentioning. One is Leslie Rice’s four panel, paint on velvet portrait of Adam Cullen, Quartered, drawn and hung: Adam Cullen on public display. Using the faux-Classical architecture of the Art Gallery of NSW, Rice has executed a witty portrait that makes a much better use of the setting than Rodney Pople’s grab bag of references for his crowd pleasing Art is what you can get away with – self portrait. It’s a pity Rice’s work has been just about killed off by the flat lighting of the gallery. The other portrait is Xu Wang’s portrait of Nick Waterlow. We found this picture quite disturbing because although we know that Mr. Waterlow is a nice man, we also encountered him après pints at the Three Weeds Hotel. Looking at Wang’s portrait we could easily imagine Waterlow shouting at passing cars and saying “fuck” very loudly.

Joanne Currie Nalingu, The river is calm.

The Wynne Prize is pretty much a write-off in 2008. The winner – Joanne Currie Nalingu’s The river is calm – was an excellent if unexciting decision in a line up of very ordinary paintings. Many years ago we were given some good advice on how to approach big shows; walk around the exhibition once quickly and return to anything that caught your attention and give it as much time as it needs. Unfortunately for the Wynne we found ourselves walking out the door and not going back. We did note that Alexander McKenzie was back with another of his is-it-Canberra-or-is-it-Europe-? landscapes while Lucy Culliton’s Hartley Landscape – cactus garden had us wondering why Karl Maugham had entered. Christian Lock’s The Secret Spot ,with its dark, underwater ambience and curvy white lines was nearly enough to make us stop, but not quite.

Rodney Pople, Stage Fright.

Which brings us to The Sulman Prize. Unlike the Archibald, the Sulman is judged by one artist, which raises the possibility that a fiercely individualistic view of art will shoehorn some unusual and interesting finalists into this dowdy genre painting prize. In theory it might work, and in practice we recall the Mike Parr and Imants Tillers years when the Sulman was a genuinely challenging proposition, but on the whole the Sulman is a not very exciting prize, largely overlooked by AGNSW publicity and stuck out the back on the way to the coffee shop. The overriding conservatism of the Sulman might have something to do with the fact that for as long as we can remember the prize has been judged by an artist represented by Sherman Galleries. This year was Robert Owen’s turn. Maybe now that Sherman Galleries has become The Sherman Foundation things might change, but given that Dr. Gene and Brian Sherman are major arts benefactors, it’s unlikely. The best we can hope for is that Shaun Gladwell or Monika Tichacek will get a go sooner rather than later.

So what did Robert Owen come up with? His winner was Rodney Pople’s Stage Fright quoting George Stubbs. Should a painting of a zebra win the Sulman? Even one that’s not nearly as good as the original? Sure. Pople is an eccentric artist who has scored a trifecta this year with paintings in each of the prizes, perhaps imagining himself in the exalted company of Brett Whiteley and winning all three in one go. What a vindication of effort that would be, and what a pay day! We have to admit to a collective feeling of good will and joy that this perennial outsider has made some inroads into the competition. But the doubts niggle that his painting was the best in a pretty rough year. As much as we may wonder what a different judge might have made of the entrants the prize is only as good as the artists who enter it. The whole Archibald/Wynne/Sulman prize season at the AGNSW has become such a debased circus that most contemporary artists are giving it a miss. They’re voting with their $50 entry costs and cashing in at the Moran Prize for Portraiture.

Fiona Lowry, What I Assume You Shall Assume (Self-portrait)

It seems bizarre to recall that Doug Moran started his prize in competition to the “avant garde” Archibald, imagining a portrait prize for regular people who don’t have to be famous but are just interesting to look at. All these years later the Moran is on the cusp of becoming the leading prize of its kind. And it’s all down to the judges. Whereas the Archibald is a farcical popularity contest among cashed up millionaires with no knowledge of art outside of liking it, the Moran this year was judged by Ben Quilty and Doug Hall AM. Fiona Lowry’s self portrait What I Assume You Shall Assume (Self-portrait) was a fantastic win for a young artist with an identifiable personal style which is, ironically, just as “decorative” as Barton’s, yet has attracted nothing but praise.

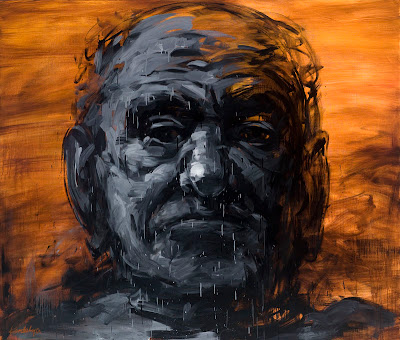

Kordelya ZhanSui Chi, Jack.

The Moran Portraiture Prize, along with its companion photography prize, is staged at the State Library of NSW. Although not really set up for exhibiting large scale paintings, the 19th century ambience of the Library’s exhibition halls give the whole enterprise the atmosphere of a salon hang. Some works do ok while others such as Kordelya ZhanSui Chi’s Jack struggle to find some space in which to sit. Chi’s monstrous head hangs on a temporary wall masking an air conditioning unit. For a brief moment we hoped the tubing and machinery might be part of the work. Overall the Moran prize is a good year, with particularly fine works from Nigel Milsom, Louise Hearman, Seth Birchall and Noel McKenna. If there’s anything to be learned from contrasting the Archibald and the Moran Prizes, it’s the realisation that for a prize to have any relevance, to attract some good artists and grab some attention, judging decisions have to be bold, adventurous and brave.

is you artwork even if it means the end of you a self portrait