International affairs editor John Kelly decided to temporarily ditch art criticism after a run-in with an arrhythmic sound artist – and review a staging of Harold Pinter’s The Guest House…

You can almost feel the historic tensions in the worker’s cottages crammed down the narrow lanes, right under the Shandon bells. The blue and white acrylic sign reads ‘Guesthouse’ which has many associations; from the homely B&B to a place where refugees are sheltered, or maybe pungent bed-sits, inhabited by the old, the homeless and the desperate. This could be part of a set for a Harold Pinter play, our Guesthouse however has a delicious smell emanating from the kitchen where ‘vegan something’ is chalked on the board and a healthy collection of cosmopolitan artists and students mingle over food and wine.

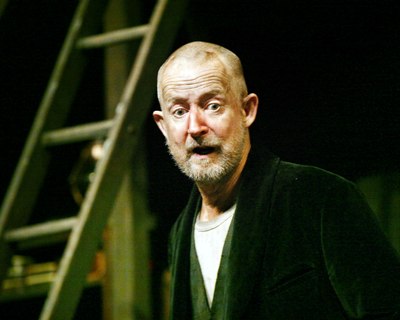

Today’s chef, Gavin, a sound artist, is later to be found in the project room leaning over a mass of equipment making ‘noise’ in an untitled performance piece. He begins by taping a mike to a radiator and then amplifying the sticky tape as it is pulled away. As the performance progresses his mass of grey hair bobs to a beat that I struggle to hear let alone imagine. The hair comes dangerously close to a working seed grinder that luckily has a lid on. There are no pauses or silences and the wall of noise continues for 20 minutes, unrelenting. Sound Art and great food are main courses at this artist run space in Cork.

The night before I saw Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker in the beautifully titled Everyman Palace Theatre. As it was written in 1960 it seems timely that I see it, for it resonates with ideas of delusion that just might be the defining feature of our epoch. Like banks will self regulate and measure their decisions against long-term benefits to the community! The following morning just before setting off for the Guesthouse I decide that for the next 24 hours I would be a theatre critic. Why not? I am as delusional as a sound artist bobbing to a non-existent beat or a banker with a social conscience. Let’s be who we want to be, even if just for a day.

In Pinter’s play, Jenkins or is it Davies, one is never sure, is a homeless man invited into a room by Aston. He is offered the position of caretaker firstly by Aston and then by his brother Mick. All three characters have limited but definable ambition. Aston wants to build a shed but seems incapable, his ‘brother’ Mick wants to develop his building business and Jenkins/Davies wants to get to Sidcup, so that he can regain his real identity. The dialogue that is at times disconnected seems to be one of absurdity but it may not be as incongruous as you might think at first. To unlock the meaning of the narrative imagine another. If Mick the builder who supposedly has a van, built the shed for his brother and then drove Jenkins/Davies to Sidcup then this play could have all been over in 5 minutes and I would have been home to see the ‘Special one’ take Inter-Milan to a Champion’s League victory. However this could not happen because in Pinter’s ‘reality’ the men could not leave their house. They are trapped in a reality that is inescapable and just as the characters deceive themselves Pinter dupes the audience. He does so from the very title of the play. Once you understand this a great deal of the absurdity dissipates.

The title Caretaker is initially read as meaning that Davies/Jenkins is being offered a position where he looks after the run down guesthouse with duties including that of a handyman, which he is totally unsuitable for. That is what he believes in any case and this is reinforced by the noise of water leaking into a bucket. However ‘care taker’ could also be read as one who is in need of care and willing to accept it. Maybe we are actually watching three men suffering various forms of mental health problems in a mid 20th century institutional care home that is so poorly funded it is literally falling apart? In it three men battle over the two beds that are in a dormitory, their racism and bigotry not allowing them to move to the room next door where “black” men live. That Aston and Mick are ‘brothers’ should be read in the Afro Caribbean vernacular. It’s a nice counterpoint. The names Aston and Mick also tell you they can’t be related in the same way as Aston and Martin are.

Aston openly admits he has been in a mental institution a victim of involuntarily shock treatment. Davies or Jenkins is a homeless man with no papers who by all accounts smells and Mick is threatening and at times a violent man who the others assume is capable simply because he has a van. The three men could be symbols of the English class system with the nice upper-class twit, a violent tradesman and an unreliable out of work ‘tramp’ representing a world of 1960’s English stereotypes where the underclass are Irish or Welsh, violent and dirty who eventually outlive their usefulness and end up in the guesthouses of Kilburn, with their stories of why it didn’t work out. Or did Pinter simply foreshadow that? I wasn’t born in 1960 so have no way of knowing.

The play also explores the idea that each and every one of us is in search of some sort of ‘recognition’ and this search is a fundamental aspect of human identity. It is why a man is making sounds in Shandon and amplifying them so that they assault the senses of his audience. However he has paid you off by cooking you a delicious curry beforehand. No such thing as a free lunch as they say. Therefore we stay and listen to his noise and he is rewarded with a polite clap at the end. The state funded Guesthouse gives him recognition! Pinter on the other hand shows us that if we are not recognised we descend into an absurdity and will even create fictional realities that rationalise the reasons why we haven’t got to where we should be. Aston believes he has been physically abused. Mick’s business suffers because he is looking after his helpless ‘brother’ and Davies/Jenkins needs his proper identity before he can begin to think of being recognised for the man he might be. Their delusions are that if they build a private space, take a long journey and forge a future career, they will free themselves from the physical and mental straight-jackets they exist in. But we know they will never achieve it for they are not existentialists. They create beliefs where there are none. It is frighteningly familiar.

These three-broken men, all played brilliantly, grind the audience down as effectively as a seed grinder, their dialogue interspersed with pertinent silences that linger in the memory. Whereas Pinter uses noise and the lack of it to emphasise his language the Sunday Guesthouse performances, coincidentally also by three men, created a lot of sound but little significance or meaning. There noise seemed more a wail for attention than a language that heightened my reality. But then the vegan dish at the Guesthouse was much more interesting whereas all Aston offered Davies/Jenkins was a white sandwich. So where would you rather be – in Pinter’s guesthouse or Cork’s?

Artist: Gavin Prior

The Guesthouse

10 Chapel Street,

Shandon,

Cork

The Caretaker

Mon 17 – Sat 22 May @ 8pm

By Harold Pinter

Everyman Palace Theatre, 15 MacCurtain Street

Cork, Ireland.

Presented by London Classic Theatre

Bopping to beats not percieved by others is not only enjoyable for me but it provides a regular pulse against which I can measure and feel the irregular and extended pauses between utterences. So there’s another link with Pinter for you. When playing electronics we can can generate noises which excite the body while expending less energy than it takes to play regular instruments. Channeling some of this excitement through the body rather than the hands on the instrument makes it easier to play with restraint.

You put noise in quotation marks which suggests you’re not into or familiar with noise music. Those who are don’t look for the significance or meaning that can be created with words.

For the record:

I was performing as half of the duo Toymonger. Fyodor also performed a separate solo set.

I received no state funding for my residency in The Guesthouse which I did at my own expense apart from food and lodging provided by The Guesthouse.

Dear Gavin

Thank you for your response.

Your initial comments speak for themselves, however I do want to address a few issues so there is no misunderstanding.

Seeing Pinter’s play the night before was coincidental, combining them in the review was not. As you seem to acknowledge the idea of an audience looking for something that may or may not be there was the point of this analogy. It was pertinent to your performance and also to Pinter back in the fifties.

You contradict yourself when you say you received no state funding. The Guesthouse provided your lodgings so even if indirectly they helped fund your stay in Cork. You seem defensive about this matter. The point I wanted to make is that it is very important that artists are acknowledged by the state and receive recognition. If artists are not critically recognized for their work, then their sense of self as an individual and ours as a community is lessened. This seemed another aspect that made Pinter relevant and are emphasized by your comments that make sure your colleagues are recognized, even if under their stage names.

The Guesthouse plays a vital role to providing recognition to artists in Cork and is one of the success stories of Cork’s cultural life over the past few years. I would be disappointed if my review is in any way read as a criticism of this organization. Visiting artists are an important function of The Guesthouse and should only be encouraged.

I used quotation marks with the word noise to differentiate it as your art.

I look forward to your next visit.

regards

John Kelly

John, I hope you’ll forgive the tardy response. If I seemed defensive I think it was because the phrase “wail for attention” was used while mentioning that the Guesthouse receives state funding. Babies wail for attention but good musicians have other motivations. Reading between the lines I got a whiff of “I can’t believe taxpayers have to fund this nonsense” You comment shows that you don’t actually think that way. There are easier ways to get attention and recognition not to mention state funding than playing noise music.

That lunchtime concert was fulfilling afternoon but the main purpose of my residency was to gather field recordings for an audio collage of Cork city which I’ve just released as a free download.

http://desertedvillage.bandcamp.com/album/babbleon-cork