Thinking about curating an exhibition on the subject of landscape is to consider what’s meant by ‘landscape’ and, by extension, how the traditional genre of landscape painting is wholly inadequate to describing the 21st century. If you’re in the least bit aware of the state of the world, and its past and potential futures, then the ‘landscape’ would have to be one of the most problematic of all curatorial adventures.

Such was my own thinking when I curated Another Green World for the Western Plains Cultural Centre in 2017. The solution it seemed, was to acknowledge that our thinking and attitudes to the land are shaped by cultural memories, and of form and meaning in art that takes on that subject.

Halinka Orszulok, winner of the Glover Prize for landscape painting in 2018, and who has curated Uncertain Territory for Art Bank, is of like mind. Orszulok’s show surveys the ways in which the land, environment, culture, and a shifting sense of subjective response, give rise to a different account of the subject. In essence, the works talk of our experience of being in a place, united by a sense of unease, and uncertainty.

At one end of the curatorial idea is a cluster of works that are about the land, but in radically different ways. Tina Havelock Steven‘s video Giant Rock [2017] features the artist at her drum kit, drumming away, as the camera flies in, then out, and out, and out, to reveal that what at first appears to be a cave, or the side of the hill, is a single stupendous rock somewhere in a desert. The drumming is mute, and in its place is an eerie hum and the faint background chatter of voices. Not knowing anything about the site does nothing to diminish the work’s uncanny power, but to then read in the exhibition notes that the site in California is a sacred site for its indigenous people, as well as a US government weapons testing range and a magnet for UFO nuts, seals the deal. Some places just seem to resonate a meaning beyond words and Havelock Steven’s video transmits this straight to the senses.

By contrast Uri Auerbach‘s The Western Lands [2018/19] is wholly inscrutable. Something scientific is going on – a series of three glass beakers, tubes, clear liquid inside, some blinking lights – the apparent link to landscape tangential and obscure. The title suggests a link to William Burroughs‘s The Western Lands, where the cowboy sagas and cities of the red night that appeared in his previous novels, give way to a hallucinatory conflation of autobiography, ancient mythology and a journey through the Egyptian land of the dead. While Auerbach’s work might suggest the life force of water, and its importance in the biosphere, with the Burroughs link the work becomes more about the transcendence of physical and spiritual form.

Raquel Ormella‘s Australia Rising #1 [2007], a wall hanging in patriotic colours of green and gold, and featuring the words MUTUAL OBLIGATION, feels both festive and mandatory. Dating to the last years of the Howard Federal Government, the work is a reminder of how a concept of country, and by extension a nation itself, is conjured out of a consensus view of who we are and where we come from. The nation stops at the borders, and in Australia [with a few notable exceptions], that is literally the land. We will decide what is art and the manner in which it is delivered to us.

True Colours [2016] is a part of Daniel Mudie Cunningham‘s somewhat obsessive series of reenactments of classic 80s video clips – this one a drag on Cyndi Lauper’s 1981 hit of the same name. Cunningham stands in for Lauper, and the multi-racial casting of featured players attests to a very different notion of country, but it’s the artist’s own performance that’s central to the work. Reimagining the location of the Cronulla Riots as a space for queering identity, Cunningham gives the performance his all, particularly as he gazes Narcissus-like into a mirror in sand that looks remarkably like the map of Australia.

Orszulok’s own painting practice, represented here by two paintings of urban nightscapes, might eschew some of the more obvious conceptual and performative elements of the works discussed so far, but for me I find them somehow comforting. As though viewed through a night scope or captured on slow film, the artist’s fastidious brush work in oil gives her images the lustre of a dream, one both familiar and unsettling. As much as one might imagine the art of landscape painting is kaput, it’s always surprising that wth an individual eye, the landscape can look new again, even one that appears to be undead.

Alanah Hunt‘s video en Masse [2016], projected adjacent to Orszulok’s canvases, shares the same kind of objective sensibility. Recording the arrival of grasshoppers in the Kimberely Region in Western Australia, the video is a static frame, but within it the insects buzz and birds hover, the whole frame a swarming pixilated action. Like Orszulok’s pictures, Hunt’s video has a scientific, objective eye, but with an artist’s understanding of what makes a compelling subject.

I must admit a great love for Alex Wisser‘s hole digging adventures. It’s not just because they remind me of the kid in The Castle always busily digging up the back yard, but also because they so deftly conflate a performative action – and an attendant history of land art – with a demonstration of how literally the land is made. Here are the layers, this is what is required to see it. Where spiral jetties, monumental trenches or hollowed out volcanoes have the same grand gestures as a lost civilisation, Wisser’s practice is human scale, modest, like a solo miner’s work that brings to mind another movie – for every modest excavation, there is potential knowledge, and potential wealth involved: there will be blood.

An outsize presence in Uncertain Territory is the wall dedicated to the ‘didactics’ that explain the activities of the Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation, and its associated projects around land use and regeneration. It is at this point where my appreciation of the possibility of an art of the land reaches a kind of aesthetic limit – on this side are paintings, videos, installations and so on – and on the other side are banners and posters that tell you what the project is, what the artists have done, and so on. I can appreciate the projects, and support them, but as a gallery experience they remind me of the old adage, show, don’t tell.

One of the KSCA artists is Georgie Pollard, whose sculpture The Long Sleep [2018] is located in the gallery’s foyer, and it’s an ideal example of suggesting without simply saying. A bed that’s covered in objects made from bio char [a material that sequesters atmospheric carbon] suggests both a present and possible future for the planet, a method of extracting human-introduced carbon, but also memorial for a human past in a post-anthropocene future.

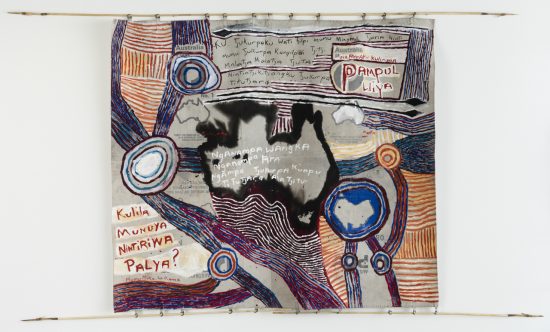

The abstractions and conceptual uncertainties of a relationship to the land tend to melt away when your land has been taken from you. The presence of Mumu Mike Williams and Sammy Dodd’s Postbag Painting anchors the exhibition in the reality of land. Using post bags as a bee to create a map, and to declare the cost of transgressing traditional law, the work has an undeniable urgency. The work states in part that:

Do not damage our cultural heritage. Theft or misuse of this Tjukurpa is a criminal offence. Penalties apply. Theft or misuse of this land is a criminal offence. Penalties apply.

Uncertain Territory, at Art Bank, Sydney, until May 18, 2019.

That’s the most informative story to tell and please early childhood development is key on art

Pingback: Museums, art fairs, nationalism, photogenic drawings, epicurean adventures + dead malls… – The Art Life

Pingback: A curator’s dream, capturing nature, Kyneton Contemporary, return of giant rock + more! – The Art Life