Art Life editor Andrew Frost likes to drive very long distances to see art. What he found in Castlemaine Victoria offers a few clues how regional arts events can reshape Australian art…

Staging visual art in regional Australia is a complicated business. Whether it’s an exhibition, a festival, or some other sort of temporary event, a range of fundamental questions come into play: who is the audience? And where do they come from? And of course, that perennial question: who puts up the money to make it happen and, when it’s all over, how is its success measured?

For the most part, visual art in regional Australia is seen in the context of regional galleries, supported by local councils and authorities, sometimes with additional funding from state and national governments.

And given the remit of regional galleries, and the not unreasonable expectation that any kind of exhibition or festival will be focused on a local audience first, and cultural tourists second, there tends to be a fairly conservative response to what is shown.

While there are many regional gallery directors and curators working within limited budgets who have staged impressive and important shows, it still feels like there’s a way to go before regional arts can reach a critical mass, and not only have their efforts recognised, but be taken seriously at the same level as city based shows and festivals, while drawing in both local and visiting audiences.

What’s at stake is the recognition that the regions in Australia are vital players in the ecology of contemporary Australian art. After the museums and galleries of the major cities, and the commercial galleries sector, regional galleries are a vital element in the process of exhibiting art, promoting it, and educating audiences. What’s been missing in regional arts are large, accessible and well curated shows, exhibitions that could challenge the hegemony of city-based biennales, festivals and other large events that draw on the resources and expertise of multiple exhibition partners. And that’s no easy task.

Of course, geography plays a big part. Staging an event in a regional city or town whose nearest neighbor is say 200ks away seems daunting to everyone but the most dedicated country driver and, as has been shown on numerous occasions, even great exhibitions relatively close to Australia’s capital cities can go begging for an out-of-town audience.

In that context, the recent [>] Castlemaine State Festival [CSF] seems to have hit the literal sweet spot. Just ninety minutes from Melbourne, this biannual culture festival is staged in a town with fewer than 7,000 citizens, but which has four live music venues, an ongoing cinema program, an art museum, energetic local radio and a huge network of resident artists, writers and musicians. It’s an historic gold fields town that’s just 30 minutes from Bendigo and La Trobe University’s art school.

While the festival itself is well established, with theatre and live music, until this year its visual arts component had been considered as a bit of an afterthought, a mere gesture toward recognising its potential as a focus for contemporary art.

The big play for the festival in 2019 then was the introduction of a curated art program situated in various venues across town, with 28 featured artist in the main program, and supplemented by 56 open studios, a series of talks and presentations, and a renegade and sometimes anarchically unofficial visual arts Fringe.

Curated by La Trobe University’s Kent Wilson, the visual arts program succeeded well beyond its modest means. The work was mostly of a very high standard and the show avoided an overarching curatorial theme, instead letting visitors to draw threads from across the venues and respond to works as they please.

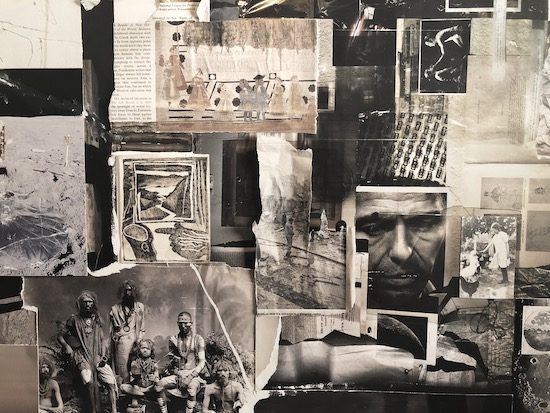

The Castlemaine Art Museum, located in the centre of town, was one of the major CSF venues. It’s a 19thcentury building, with high ceilinged galleries and a subtly controlled mix of light, with period gallery furnishings, giving the spaces inside a regal feel. The disruption of that ambience by CSF work was curatorially astute; Lyndell Brown and Charles Green’s series of re-photographed collages 100 Years of Disaster[1918-2018] rewarded a considered viewing. The collision of found and repurposed images, some of them drawn and painted over, other images mashed together, are presented in the classic collage style. Hayley Millar-Baker & James Tylor’s Dark Country[2019] was a series of four large digital collages surrounded by smaller framed pictures that have had circular, square and rectangular holes cut into them, creating black voids. The work’s heightened suggestion of place, and the withholding of detail, effectively dramatised first contact stories between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous occupiers, and the denial of that history.

Just down the street is the Castlemaine Market Building, another colonial era edifice that hosts on one side, the town visitors’ centre, and on the other two temporary gallery spaces. Where the Castlemaine Art Museum has the presence and authority of a conventional galley, the Market Building’s spaces felt temporary, especially for subtle pieces such as James Carey’s installation of piles of dust, and gold leafed bowls of water, and Jazoo Yang’s earth toned assemblages.

Where these pieces worked in contrast to their exhibition space, Robert Hague and Damien Shen’s Where We Meet[2019] took up the entirety of the adjacent gallery with a considerable material presence. The duo’s ongoing collaboration investigates the ways in which biological difference has been scientifically recorded and used for a variety of dubious purposes across the centuries. Using body casts, photography, x-rays and DNA tests, the coincidences and convergences between the two artists and their racial and cultural backgrounds produces a kind of compelling double self-portrait.

The other major CSF visual art program venue was the Old Castlemaine Hospital, a place that’s a testament to the municipal will to repurpose an old building, converting its old surgeries and wards into offices, studios and creative spaces.

While I was told the building and its new function has been a failure, and will soon be torn down, fthe installed works there by a number of artists including students from La Trobe University art school, were a testament to a never-say-die anything-goes spirit.

The works were for the most part orthodox sculptural installations, video pieces and other student-level works. The standouts at the Old Hospital were Dale Cox’s Castlemaine Warriors – A Revisionist History for the Post Truth Era [2019], an elaborate installation and pseudo-documentary video that explores what happened when ancient Chinese terracotta sculptures are discovered in a local field, and what it means that their heads look like Mickey Mouse.

In the basement of the hospital was Michael Greave’s Movements and Traces, Articulations and Reverberations[2019], an installation of inscrutable minimalist beauty, a series of paintings produced in response to the resonant space [formerly the hospital’s ICU], and a drone sound work generated by the feedback produced by old record players and speakers.

Along with these major venues, the CSF visual art program was to be found in a number of other locations, including The Mill, a successful repurposing of an old industrial site into markets, bars and cafes, and which featured three hard-to-find art works.

Around the corner is the New Northern Art Hotel, an old pub with a museum quality exhibition space out back, featuring the work of Abdul-Rahman Abdullah and Anna Louise Richardson, and in the bar, Melinda Harper.

Another satellite venue was Lot 19, located literally on the other side of the tracks, down a dirt road in an industrial zone. This neatly tended venue is an artists’ Shangri-La, a series of studios, gallery spaces and purpose-built workshops. This is where you can find Cameron Robbins’ Shadow Phase[2019]. Using hand built machines that respond to changes to the intensity of sunlight and wind, Robbins’ contraptions guide a pen across a roll of paper producing abstract drawings that are aesthetically beautiful environmental recordings.

The CSF visual arts program was much like most other art exhibitions staged over multiple venues with various artists. It had its high and low points, and its organizational eccentricities, but for a show that was on for just ten days it had an overall quality that was equal to most large exhibitions, be they in the city or in a regional centre. The balance between local representation and visiting artists, despite some grumblings I heard along the way, also seemed to me to be well judged. And with the critical mass of attention that the festival brings to the town, having a credible visual arts component is a major draw for both visitors and townies alike.

The regional arts sector is one of the most important but undervalued in Australian art. It caters to a vast number of people outside the cities, and has the dual role of educating and informing its audience. While many have tried to achieve ‘the Bendigo effect’ – having world-class exhibitions, festivals and events and having an audience to match in a regional centre – few have achieved it. And that’s because regional arts by definition is largely isolated, in both outlook and audience.

The Castlemaine State Festival, with its newly minted visual art program, offers a model for how those much vaunted outcomes can be achieved – the strategic partnerships between local galleries and governments across geographically nearby locations, with a view to drawing in the audience from the region and beyond.

The idea of a regional biennale, a region-wide festival collaboration between multiple local governments and galleries, is an idea that is yet to happen in a meaningful way. As for the CSF, I suppose only the final measure of the audience and where they came from will answer that perennial question of achieving critical mass, but for now I think we’ll soon be talking about the ‘Castlemaine effect’.