Din Heagney flips us a history of the finger…

SOCRATES Well, to begin with, they’ll make you elegant in company—and you’ll recognize the different rhythms, the enoplian and the dactylic, which is like a digit.

STREPSIADES Like a digit! By god, that’s something I do know!

SOCRATES Then tell me.

STREPSIADES When I was a lad a digit meant this!

[Strepsiades sticks his middle finger straight up under Socrates’ nose]

SOCRATES You’re just a crude buffoon!

STREPSIADES No, you’re a fool— I don’t want to learn any of that stuff.

SOCRATES Well then, what?

STREPSIADES You know, that other thing — how to argue the most unjust cause.

The finger. The bone. The bird. The flip. The flash. The solo salute. The extreme extremity. The up yours! Our humble middle finger has a long and prodigious history, first documented almost 2,500 years ago when Aristophanes wrote The Clouds. This ancient Greek play tells of Strepsiades, an old man desperate to fight off his creditors who seeks out the assistance of Socrates to learn the art of argument, only to give the famed philosopher the finger in his haste for knowledge. The Clouds presents the case for good argument, balanced out by some lessons in the social and personal dangers of having good oratory skills and defensive tendencies with your digits.

Over the centuries, little about us has changed when it comes to the control of our central dexterity. The middle finger still comes out when emotions rupture the tongue, imprecation fails, or when an abrupt message needs to be delivered in the least ambiguous manner. The Romans divided the application of the middle finger into two classifications: digitus infamis (the infamous finger) and digitus impudicus (the impudent finger), although which was which seemed to depend on your social status and possibly how many slaves you owned.

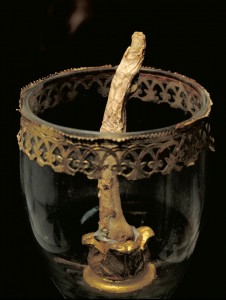

Then there is the rather classic up yours tale of the longest finger. In 1737, a grave-robber named Anton Francesco Gori busted into the tomb of Galileo and stole a few odds and ends, including the digitus medius of the famous stargazer. For centuries the finger made its way through a number of private collections, partly preserved inside a golden glass egg. Since being recently rediscovered, the astronomer’s dead digit made has its way into Florence’s collection at the Institute and Museum of the History of Science. It would seem that despite being persecuted for his beliefs about the cosmos, Galileo got the final word. Or the final flip to posterity at least.

Catalan’s L.O.V.E…

So why am I giving you this rather useless history lesson? Well, I’ve been considering Maurizio Cattelan’s L.O.V.E. and Ai Weiwei’s Study of Perspective series — artworks centred on the middle extremity, made by title-holding heavyweights of the contemporary art world. These two infamous works, while similar in subject, have left me with this lingering question: does success combined with offense become a wink to subversion or something altogether different? There is a certain incredulity that accompanies renegade artwork made by those who profit most from the market’s excesses.

Ai’s photographic series of fingers to the establishment endeared him to a new audience when it was first shown at the Shanghai Biennale back in 2000. While many people read the photographs as disrespectfully droll, it would appear that you might bite the hand of the master if your sales records have a sufficient number of zeroes after the dollar signs. Ai gave the finger to the Forbidden City in Beijing, China’s embodiment of its dynastic history that he apparently loathes, yet simultaneously collects relics of antiquity for his adapted readymades. Ai photographed himself giving the finger to other institutions that represent historical and institutional dominance. The White House in Washington copped his flip, along with the Eiffel Tower, San Marcos Square, and the Louvre. There was also a flash for the Orangerie Palace in Kassel, even though he would later go on to present a major project for Documenta, a more socially open and interactive work that was possibly more effective than his political statements. Writer Carol Yinghua Lu later remarked “Ai’s provocative remarks and his critical and irreverent stance towards authority run the risk of becoming an empty gesture…”

This work raises another question, should you choose to publicly give the one finger salute to an institution somehow deserving of your displeasure, how do you consciously reconcile accepting financial opportunities funded and organised by those same institutions? Perhaps disrespect leads inversely to respect? This series leaves me a little skeptical of statements from Ai such as: “I don’t like anyone who shamelessly abuses their profession, who makes no moral judgment.” Does impropriety really assist in the development and promotion of morality? Also, I hate to say it, but artists are not the moral guardians of humanity. Still, Ai has a good point.

Galileo’s finger…

Meanwhile and more lately in Italy, where the authority seems to relish offensive behaviour, Maurizio Cattelan’s 11-metre tall middle finger called L.O.V.E. took pride of place outside the Borsa di Commercio di Milano, the centre for commerce in Italy and a symbol for western economic wealth and power. Critics at the time suggested Cattelan was giving the finger to the financial establishment following the global financial brouhaha, yet this doesn’t translate in the presentation of the work. Positioning a sculpture on a plinth — where it is directional in form and designed to be seen primarily from a certain vantage point — would indicate that this work represents an outward facing concept, the hand of the Borsa. In the same way that the tradition of religious sculptures in Italy are designed to inspire the beliefs in the institution framing them, so the finger of the stock exchange can more clearly be seen to represent the malevolent “love” of the economic system toward the public, configured here by facing the object onto a public square, the Piazza Affari. While the work was commissioned for Cattelan’s retrospective — and was later offered but rejected as a permanent installation for the City of Milan — it is neatly tied into an artistic and critical tradition. If the Borsa Italiana is literally giving the finger to the public it controls and feeds from, it takes no morality to realise the two-way critique at work.

It is true that art can sometimes point our collective moral compass in the right direction, as Ai might demand of artists, but in a world supposedly bankrupt of both public monies and prevailing morals, making ‘crude buffoon’ gestures becomes only mildly amusing. In the end, these works may do very little to advance the argument for or against today’s ‘unjust cause’ – the same kind that drove debt-laden Strepsiades to prematurely give the finger to Socrates so long ago.