Over the last few years John A Douglas has been exhibiting his ongoing Screen Test series in various artist run galleries. His latest work is now on show in the ambitious exhibition Screen Test [Americana/Australiana] – Fragments and Stills at Chalk Horse until May 17. He spoke to the Art Life about the project…

Could you explain the genesis of the show?

John A. Douglas: The initial idea for the Screen Test project began in late 2003 when i was curated in a group show at First Draft. I was interested in investigating cinema as a mode of art practice and using the idea of a screen test to perform fragments of film. At the time, I was starting to build an extensive home library of DVD and I remember looking at a few Hitchcock screen tests as a DVD extra (from Rebecca, I think) which sparked the idea of creating my own version of a Hollywood screen test. The concept was very simple: to perform a simple action selected from a specific point in a film, to follow a set of written instructions and perform them, which is in essence what a Screen test is (and really, if you think about it, can be used to describe the cinematic process as a whole). I later found out that Andy Warhol had also played with screen tests in the days of the factory so there was a precedent to this in terms of a legitimate art practice. People often ask why don’t I just make movies but I think that it is only in the realm of art practice that the aesthetics of cinema can be realised. This has been true for a lot of artists since the 70s. I also wanted to explore the relationship between the moving image and the film stilled so there was also the beginnings of shooting staged photographic tableaux as a film still. Artists such as Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall and Bernard Faucon had constructed cinematic images however I wanted to create photographic works that inhabit cinema itself. The current exhibition is the outcome of these investigations and the six photographs and videos span 20 years of cinema history from 1950 – 1971. I also wanted to create a relationship between the cultural aesthetics of Hollywood interior and the light and space of exterior locations in Australian cinema.

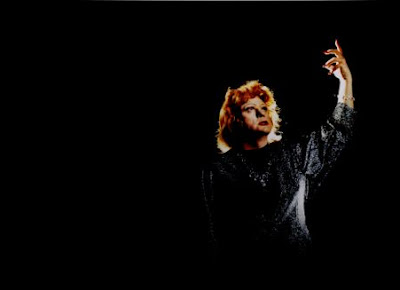

John A Douglas, Screen Test #1(Americana), 2008.

C-Type photograph on alluminium, 1400mm x 1000mm.

Your choice of films to quote seems very idiosyncratic -are they of a particular personal resonance for you?

JAD: Yes, each work is highly subjective and draws upon personal experiences. But the very nature of how cinema is perceived is contingent on this subjectivity. Lacan believed that cinema works at the level of symbolic mirroring of the self so that what we see on the screen is a projection of our own ideas about how we perceive ourselves and others in the world. This has the possibility of bringing cinema into the realm of the political where cinema can be used as a tool to perpetuate specific ideologies about society in general. There is no doubt that Hollywood has played a major part in the perpetuating of American ideologies worldwide especially in this country. For example, with Screen Test #1, I perform an action from the Billy Wilder film Sunset Boulevarde. This work was a direct response to my own experience of being an aging emerging artist who graduated from art school when I was 42. It’s not easy when you look around and see that those that make it in the art world and in fact any of the arts (especially artists who place themselves in their work) are young, good looking and often from wealthy families. It’s kind of absurd for a middle aged artist to be showing in artist run spaces with people 20 years younger. Sydney, in particular, is a city of cultural paedophiles. In fact a gallery manager once told me I would probably do alright if I lost some weight and stayed behind the camera – they like ’em young here. So for me Norma Desmond embodies the struggle of aging and beauty which affects men as well as women. Sunset Boulevarde was interesting to me because it is a critique of Hollywood and the star system by Hollywood. The film has also been a profound influence on David Lynch. I like the sad, comic and camp irony of playing Norma and at the same time using her as a vehicle to poke fun at fame.

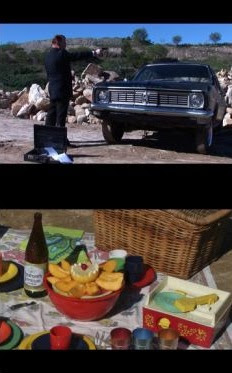

John A Douglas, Screen Test # 4 (Australiana) – A suicidal synthesis, 2006. 2 mins 30 secs.

Colour, DVD PAL, 16:9 SD with audio.

Some of these films aren’t that well known now, especially to a younger audience – do you have a sense of how these images might be read without knowledge of their source?

JAD: Actually, I am not sure whether that is always true. The availability of film via DVD and now online means that cinema is often revived by a range of audiences. Laura Mulvey in her recent book Death 24 x a Second postulates that 100 years of cinema is now consumed and exhumed from it’s graveyard at a rate that has never been seen before. This is also true for the music industry. My 15 year old nephew’s favourite bands are Led Zeppelin and the Doors so I think that because of new technologies this gives us an immediacy never seen before. This has been great for researching the work and examining each film. Online resources such as IMDB and Amazon, as well as cheap DVD players which allow for prefect stilling and slowing of film and software which allows me to create film stills on my desktop all add to the creative experience. When I was in Tokyo in 2006, I saw a group of around 20 young women all dressed as Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffanys, complete with beehives and pearls. It’s interesting that an iconic character from a specific moment in cinema some 50 years ago has found its way into the vernacular of contemporary Japanese Street culture. Essentially, I am inviting the audience to play a game where they figure out what films I am performing. In the Australiana part of the project I deliberately chose a lost and forgotten film, Wake in Fright , and the rarely remembered suicide segment from Walkabout. The relative obscurity of these sequences enhances the contrast between the Hollywood films I chose to preform and the Australian fllms. In fact when I researched these films I discovered the tragic reality of Australian cinema; both these films were directed by overseas directors because at the time it was believed that Australia was incapable of making world class films and, thus, that it was better for British or Americans to star in and direct our cinema. So Wake in Fright and Walkabout are actually an outsider’s interpretation and construction of Australian culture. Sadly, I believe this attitude is prevalent in Australia and not just in the film industry. So really, I don’t think it really matters whether viewers recognise the films or not – but if they do, it will add to the experience of the work. However the shots that I chose to use as the raw material for interpretation were also used because they look good so had a lot of fun playing around with the look of the film purely at the level of stylisation and artifice.

How do you see the photographic and video work in terms of performance? Are you concious of the limits of versimilitude when emulating the look of the original films?

JAD: My intent was to follow a set of instructions for a selected scene and actions. Each performance is an enacted moment of cinema iconography, but clearly it was also important for me not to take this too seriously. So there is a palpable sense of the ironic in these works. The earlier Screen Tests are concerned with a form of emulation, of ‘getting it right’ so to speak – and that imposes its own limits, in some ways. As the project progressed, though I moved away from the literal renderings in order to create something other than the director’s original intention. I wanted the works to become more an impression of the performed instruction and mise en scene, rather than trying to perform it exactly as it was in the original scene. These are the alternative versions, if you like. For Screen Test #5 (which is the suicide scene from Wake in Fright), my performance is of three actions by three different characters in the original film which I merged into one character. So this gives a heightened sense of those actions because they are are edited together in one sequence. I also started to play around with the look of the film (rather than replicating a set), so that the action now takes place in abandoned 1960’s petrol station (a nod to Ed Ruscha) instead of in an outback pub. Similarly, in Screen Test #4, I use a Holden Kingswood instead of a VW. That VW in Walkabout really annoyed me, actually. Surely a middle class Australian family man in 1971 would drive a Kingswood? I also extended the length of the scene and directed my own shots based loosely on the original. I took this even further with my final Screen Test, which is almost completely removed from James Dean‘s performance in Giant, and instead gives only impression of the film, relocated in the outback. Screen Test #6 (James Dean Jesus) builds on the aesthetic elements of that Giant rather than any specific scene, drawing on elements like the molasses representing oil, cattle, the car crash after the film and the death of James Dean, etc. The performance was based around the iconic shots of James Dean on the Giant set where his body forms the shape of a crucifix, and also drew on the wooden ruins Little Reatta which still satnd on the Marfa Plains. I was lucky enough to find a similar structure on the Hay Plains in NSW.

John A Douglas, Screen Test #5 (Australiana), 2008.

C-Type print on alluminium, 1400mm x 1000mm.

It’s interesting that the moments that you’ve taken from these films are quite violent, or are about violence in some way, yet their delivery is quite subtle, less overtly dramatic than the performances in the films, and have a sense of stillness. Was that an effect you were looking at?

JAD: I never thought of it like that but it’s an interesting observation. I guess my main concern in the depictions of violence were twofold. Firstly, I wanted to draw attention to the self-destructive tendencies often portrayed in films about or made in Australia as well as the highly destructive nature of male violence in Hollywood cinema. Obviously, this is why I chose the genres the western and the war film for Screen Test #2 and Screen Test #3. But the films those works were based on (WestWorld and Dr Strangelove) were a critique of those phenomena. The typical representation of masculinity in Australian cinema is full of ockerisms and depictions of hyper-Aussie men who survive on a diet of alcohol and violence, and I wanted my performance of that violence or intended violence to have an almost carnivalesque irony. Secondly, I wanted intensify the aesthetic qualities of the actions performed – and the stillness is part of that. In Screen Test #4, for instance, the action is slowed down and the shots are extended to show visual detail that is missed in the original. We see the car burning for a longer period and the destruction of the picnic set is slowed down and exaggerated to the point where it becomes visually fetishised.

The installation of the works is quite simple. A wall of images facing two flat screen TVs. Is there a dialogue between the two walls?

JAD: In showing the photographs with the video, I wanted to articulate the relationship between the motion image and the still. Raymond Bellour, who has written extensively on cinema and the practice of stilling the film, explored this relationship in the 1980s when he paused the VCR on the shot of Mrs Danvers consumed in flames from Hitchcock’s Rebecca. He observed, in conversation with the psychologist Guy Rosalto, that for him, the effect of that particular shot evoked a feeling of terror not experienced in the normal linear time frame of the motion picture. Rosalto remarked that the experience stilling a film often evokes early childhood memories of primacy and Laura Mulvey explores this too when she discusses the feelings of the uncanny evoked the slowing and stilling of the shot. One of the primary objectives of the Screen Test project was to take this fragmentation of film one step further; I wanted to become the still and to occupy and inhabit this primal territory. Interestingly, the Hollywood director Michel Gondry recently recreated a set from his film Be Kind Rewind and exhibited it as an installation at Dietch Projects in New York in March this year. He invited the audience to the perform their own versions of cinema and exhibited the set and the outcomes at the gallery. He felt that it was only possible for this to happen in the environment of the gallery. Hollywood had finally made it to the art world.