The Art Life’s senior Melbourne correspondent Din Heagney takes a bold step in to the unknown…

At last week’s Centre for Contemporary Photography (CCP) opening, I had a very funny conversation with a couple of artists, part of which went like this:

Y: You know, every time I come here there is less photography.

A: Perhaps they should just rename it the CC.

D: Centre for Contemporary.

Y: Or just fill in the blank.

A: Maybe ‘contemporary’ is a noun now.

D: Or ‘photography’ means something different from what I thought.

Anyway, I was actually there to see Event Horizon, a group show about the moon and space. It features a number of Australian and international artists and sees CCP curator Mark Feary continuing to develop his strong curatorial focus, further proving that he is well attuned to the practices of the artists he works with. Now you would think this would be a foregone conclusion in any curatorial practice but sadly it isn’t. Some curators seem more intent on extracting only their own interpretation of the meaning of a work, while demonstrating a rather annoying disregard for the artist’s actual intent. But I digress…

Mathieu Briand, UBÎQ: a Mental Oddessy Chapter 1 — A Space Perspective (La vallée des Alpes), 2007-2010.

Event Horizon sets its starting point as the moon landing of 1969 and features an introductory display of various NASA photographs and documentation, sourced through the Melbourne Planetarium. The photographs include images of astronautical equipment and test landings, orbital photographs and dust samples. Feary has also scanned and presented the detailed captions written by NASA on the reverse sides of the photos. The whole suite could be easy to look over, if you didn’t have the interest in historical documents, for instance, but you would then miss a key element of this show: one of photographs shows a detailed view of the surface of the moon, well it’s what we think is the moon. NASA’s caption actually talks about the similarities of the moon to Iceland and refers directly to Jules Verne’s novel Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

In that particular story, the adventurers must travel through an Icelandic volcano to enter the deep abyss into an altogether alien world. What is odd here, is that many decades after the book was published, and back in the ‘real world’ of 1960s, NASA was sending its astronauts to Iceland first. This freezing and sometimes hostile environment with its volcanic history would not only be a perfect training ground for the space travellers, but would supply NASA with imagined images of the moon’s surface. How different does a photo of a footprint on the ash-covered surface of Iceland look from a photo of a footprint on the moon’s dust-covered surface? In fact: not very different at all.

What starts here as a fanciful science fiction reference has been picked up as a curatorial position by Feary. The borders between science and science fiction have always been largely elusive — as any science fiction aficionado could tell you (and conspiracy theorists can just sit down for a minute here), sci-fi writers first imagined most of our recent technological advances. It has long been fiction that has inspired reality. These exact ideas are taken up by a number of artists to feature in Event Horizon, although the works included were often made years earlier, giving more gravitas to this gravity-light subject.

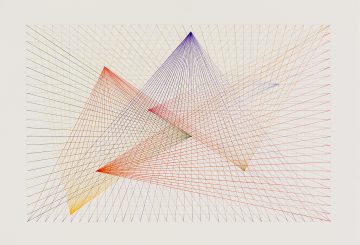

Damiano Bertoli’s elegant Continuous Movement: Classical Gas (2001-2010) enlarges the horizon line through the simple use of grid lines; the same type used in textbooks for diagrammatic representations of the solar system or as explanations of the structural possibilities of black holes. The work also provides a representation of notions around failed utopias, those imagined in both science and fiction.

French artist Mathieu Briand brings possibly the strongest work in the show, one that takes up the theme of both distance and apparent verisimilitude. UBÎQ: a Mental Oddessy Chapter 1 — A Space Perspective (La vallée des Alpes) (2007-2010) is a sculpture of pockmarked lunar surface. It is a well-made object within itself and is spot lit in the corner of the gallery with a small desk lamp, while the work rotates on a hidden motor underneath. In a nearby video gallery, a large screen presentation takes us on a rolling journey across a huge lunar landscape. The scene brings to mind some of the more disquieting conceptual imagery from Duncan Jones’ 2009 film Moon, but this landscape is not just similar to Briand’s model outside, it’s identical. What I missed here is that the sculpture includes a tiny video camera attached to the desk light, which in fact provides the live rolling feed into the other room. In one way, this work references the distances required to document space exploration and communicate across vast distances, but Briand’s work also reveals the ease of documentary forgery through simple placement and scale.

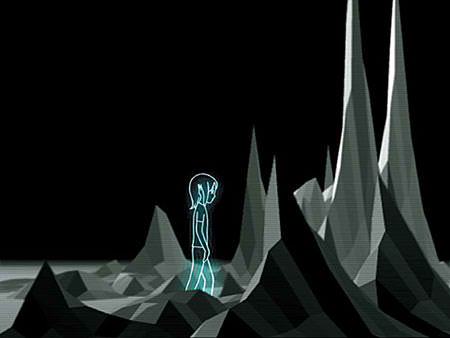

Pierre Huyghe, One Million Kingdoms, 2001

The main audio-visual work by Pierre Huyghe, One Million Kingdoms (2001), features an audio sample of Neil Armstong’s voice reconstituted through a software modulator which then recites a script featuring quotes from Verne’s classic story. The intonations and pauses in the audio track cause the video to flux with graphic versions of sounds waves that form a rising and ultimately falling landscape, but it is an imagined landscape walked by a ghostlike Japanese animation character. In isolation, the work would appear irregular, but in this show it dominates, providing the type of audio guide narration one would expect in a science museum but here is presented as a contradictory fiction.

This led me to a question I can’t get past: would this show be better suited to a science museum context rather than an art gallery context? An exhibition like this directly explores, and perhaps lightly questions, the irrefutability of science. Matthew Shannon’s almost pitch-black prints in the show, exemplify this ability for science to ‘get it wrong’. The prints reference early astronomical photography (pre-Hubble Space Telescope imagery) as we attempted to map the heavens while accidentally mistaking dust on the lens for distant galaxies.

Were we to blindly accept the old explanations of the firmament as defined by the empirical observations of past science, we would most certainly have been wrong; in the same way that the world would be a very different place if we had never moved on from Pliny’s theories or had never accepted the theories of Copernicus or observations of Galileo. And yet the futurist utopianism of outer space as ultimate destination, imagined around the time of the lunar landing, were soon dashed as the universe became more clearly revealed as a very large, very cold, and very distant place.

Despite much of the recent interest in space (through works as Peter Hennessy’s My Hubble at this year’s Sydney Biennale), Event Horizon is a quiet, but carefully considered, reminder of our deeply biased and subjective way of seeing the world around us. It shows us how our vision can provide insight into the potential fictions, as much as the flawed certainties, of our strange place in space.

Event Horizon

CCP, Melbourne

Until 18 July 2010