A Profile by Luise Guest…

Lu Xinjian in the studio, image courtesy the artist

Lu Xinjian’s early life seemed an unlikely background from which a successful artist might emerge. Born in 1977 into a poor farming family in a rural village in Jiangsu Province, by his own account his childhood was spent running wild, looking after ducks and chickens. After school he studied computer graphics and graphic design, despite his love of painting, knowing that a poor boy making his way in the world needed a more secure income than that of an emerging artist. But a chance encounter changed everything: in 1998 the influential Dutch design company Studio Dumbar had an exhibition at the art museum in Nanjing, where Lu Xinjian was studying. He didn’t have the money to buy a ticket to enter the gallery, but stood entranced in front of the posters, absorbing their structures, colour, line and form, their use of the Modernist grid. Returning to the college library, he began to read everything he could find about European design, determined that one day he would go to study in the Netherlands. It took four years after graduation to save the money, but in 2005 he graduated from the Design Academy in Eindhoven, and in 2006 from the Interactive Media and Environments Department at the Frank Mohr Institute of Hanze University of Applied Studies.

Lu Xinjian in the studio, image courtesy the artist

In Eindhoven and Groningen Lu Xinjian found himself at the centre of a particular Modernist tradition. To that point he had loved the work of Keith Haring and other contemporary American painters, but now the work of artists of the European ‘Zero’ movement of the 1950s and 1960s, such as Heinz Mack, Gunther Uecker and Otto Piene inspired him. They believed that art should be a ‘zone of silence’ devoid of personal expression. Lu Xinjian saw in this philosophy a link to Buddhist traditions of restraint and simplicity, harmony and quietude. After early experiments with figurative expressionist painting, an influential teacher, Petri Leijdekkers, introduced him to de Stijl and the work of Mondrian. He had been at an impasse, lonely and depressed during a residency in Korea, when he began to draw views of the night sky, the edges of buildings as lines and the stars as dots. The dots and dashes found in the ink drawings of Van Gogh, the grid structures of Dutch and German early twentieth century design, and the cool abstraction of Mondrian coalesced to form a new way of thinking. This epiphany was the start of his important City DNA series.

Lu Xinjian in Conversation with White Rabbit from White Rabbit Collection on Vimeo.

From this point Lu Xinjian began to paint in more abstract ways, using aerial perspectives of iconic metropolises: New York (irresistibly recalling Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie) Beijing, Shanghai, Rome, Paris, London, Los Angeles, and Venice. The first in the series, however, was the Dutch university town of Groningen, where he had taken photographs from the top of the tower in the centre of the town before returning to China. Sources for his imagery included maps and satellite views of each location, as well as photographs, but the artist sees his work as philosophically complex and multi-layered. He believes cities are built and defined by history, culture and language as much as by geography; each is distinct and unique, despite the homogenising impact of globalisation. Lu Xinjian tells the story of each city in a visual language of his own invention that merges western abstraction with simplified forms that recall the Bauhaus and Dutch graphic design, in combination with computer coding. The picture planes appear to pulsate with energy, despite their flat, brightly coloured grounds. Struggling to find a name for this body of work, Lu Xinjian suddenly saw the lines and dashes as akin to a diagram of a human genetic code. Cities, too, have a kind of DNA structure, a term borrowed from architectural practice, conveying something of the unique and complex social and architectural systems of the modern metropolis.

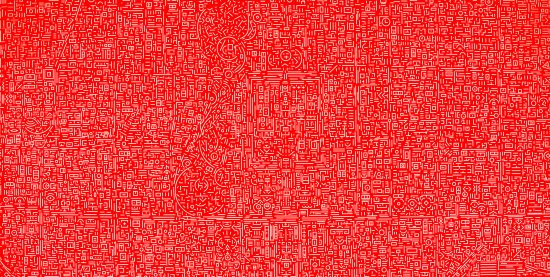

Lu Xinjian, City DNA – Beijing, 2010, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 400 cm, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection

City DNA: Beijing (2010) applies Lu Xinjian’s painstaking technique to represent the symmetrical axis of the Forbidden City, its surrounding lakes and the jumble of historical hutongs and courtyards (increasingly under threat of demolition) in lines and dashes on a scarlet ground. The artist’s source imagery is scanned into a graphics software program to create a vinyl stencil, from which each shape must be carefully unpeeled before he can paint over it, in colours selected from national or city flags. The process is repetitive and exhausting – it can take up to four days to peel off each line from the stencil over one large canvas. Lu Xinjian sees his slow, methodical practice as connected to meditation or the calming practice of Qi Gong, despite the frenetic contemporary hustle and bustle of his urban subjects.

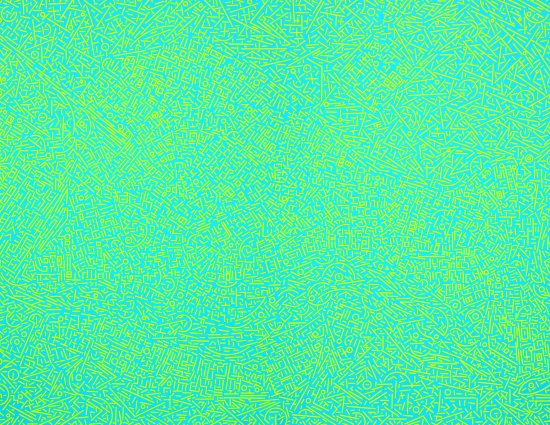

Lu Xinjian, City DNA – Venice, 2010, acrylic on canvas, 200 x 400 cm, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection

The cool turquoise ground in City DNA: Venice (2010) recalls the waters of the lagoon, its complex curvilinear forms representing the Byzantine architecture of the basilica, the Baroque churches, and the bridges, alleyways, piazzas and canals of the city. While Lu Xinjian applies the language of Western geometric abstraction, and his early training as a graphic designer, he is also connected to the Chinese master painters of the Song Dynasty. In his thinking about space and complexity, negative and positive, the creation of harmony and yin and yang, he draws upon traditions of ink painting. Mark Tobey, the great American gestural abstractionist who was profoundly influenced by Chinese painting and calligraphy, once said, ‘The line [brings about] the dematerialisation of form by space penetration.’ In Lu Xinjian’s determinedly non-gestural mapping of urban topography and human history, we see a new kind of calligraphic mark-making.

Shanghai-based painter Lu Xinjian trained as a graphic designer before becoming an artist, with an MFA in Interactive Media & Environments from the Frank Mohr Institute for (Post) graduate Studies and Research in the Arts and Emergent Media of the School of Fine Arts and Design at the Academie Minerva, Hanzehogeschool Groningen, University of Applied Sciences, in the Netherlands. His paintings and sculptures have been exhibited in solo and group shows in London, Los Angeles, Amsterdam and Seoul, as well as Beijing, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Sydney.

Luise Guest is Director of Education and Research for the White Rabbit Collection, and it was in this capacity that she interviewed Lu Xinjian, in Sydney in December 2016 and in Shanghai in 2015 and 2017.