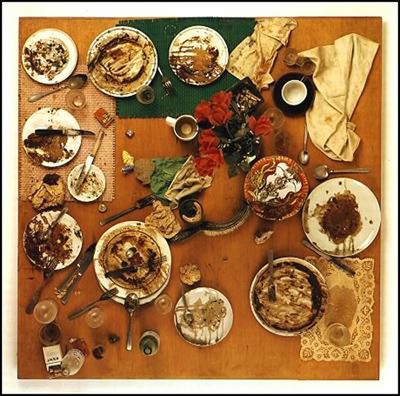

The word Biennale comes from the Italian meaning “an expensive art event held every two years”. Modeled on the Venice Biennale, The Biennale of Sydney began in 1973 and was held at the Opera House. Opened by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, the B.O.S. didn’t yet have subtitle and was directed by Anthony Wintherbotham, a ‘co-ordinator’. The 1973 B.O.S. is chiefly remembered for the fact that there wasn’t another one for three years. Realising that a serious art exhibition needs a colon, 1976’s B.O.S. was called Biennale of Sydney: Recent International Forms, a dull but honest explanation of what would be seen in the show. Directed by Thomas G. McCullough, the exhibition was launched by famed lover of the arts, Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. Another three years passed and 1979’s B.O.S. European Dialogue was curated by Nick Waterlow and featured, among other show-stoppers, Daniel Spoerri’s dirty dinner plates falling off a wall and a dead cow watching a video of a man taking a shit. Contemporary art had arrived in Australia!

The 1982 B.O.S. Vision In Disbelief set the standard for the mega-Biennale. Curated by good bloke Bill Wright, VID featured 209 artists and was spread out across the city. Including international pop stars turned artists like Laurie Anderson and Brian Eno, the B.O.S. got the punters in… and the Vice Squad cops who raided the exhibition, confiscating Juan Davila’s Stupid As A Painter. 1984’s B.O.S was swept up in giddy post modernity and instigated the still vital trend for random colons in exhibition titles. Under the direction of Leon Paroissien, Private Symbol: Public Metaphor featured big names from the US like Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger and good-time guys Gilbert & George from the UK. Paroissien, who would later go on to share the direction of the fledgling Museum of Contemporary Art, is also remembered as the guy who got a Biennale happening every two years. The cover of the B.O.S. catalogue, meanwhile, by John Lethbridge, is a time capsule of high 80s design. The 1986 B.O.S. Origins Originality + Beyond was directed by veteran curator Nick Waterlow who used the event to investigate parody, irony and the burgeoning connection between visual art and Buffalo Girls. To this end, Malcolm McLaren visited Sydney and “tagged” a wall at the Art Gallery of NSW. Only those distracted by Glenn Baxter’s amusing comic strips survived this deeply embarrassing event. It was also an opportunity for punters to get a gander at the work of rising late-80s NYC art stars such as Eric Fischl. The 1988 B.O.S., again curated by Waterlow, was called From the Southern Cross: A View of World Art c1940 – 1988, major survey of Australian art. The show toured in its entirety to Melbourne for the first and last time. Huge in scope, masterful in execution, hardly anyone went distracted as we were by fire works and Bicentennial ships.

“They’ve arrested Malcolm!” Sadly, they hadn’t.

The 1990 B.O.S, the pithily titled The Readymade Boomerang: Certain Relations in 20th Century Art, was directed by German art dealer Rene Block. With a phone book sized catalogue the B.O.S. is still paying for, TRB attempted to illustrate the entire thrust of 20th Century art looking at “the distinctive historical connections of the ‘readymade’ from the early 1900s to the 1980s, based on the work of Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and Francis Picabia.” Its heroic failure to achieve its grandiose aims is still spoken of with an ANZAC-style reverence and is remembered as one of the best BOS since its inception. The 1992/93 B.O.S. under the artistic direction of Tony Bond was titled The Boundary Rider was held over the long hot summer of December-January 1992 and 1993 and featured non-European/American artists and assorted Australian trouble-makers. The press went wild for Orlan and her brand of garish, tasteless performance art in which she attempted to transform her body via plastic surgery into a facsimile of features from famous art historical sources. Jurassic Technologies Revenant the BOS of 1996 is sometimes referred to as The Quiet Biennale because no one went. Under the direction of Lynne Cooke, JTR had a title no one understood, featured artists no one wanted to see and was held in galleries no one visited. Artistic director Jonathan Watkin’s 1998 BOS Every Day fared little better but is mainly remembered as the Biennale Martin Creed, 2001’s Turner Prize Winner, came to Australia to fill up a room on Goat Island with balloons. The title of the ‘98 BOS also had an unfortunate and startling similarity to the tag line to ads promoting the then just-opened Australia’s Wonderland [“Escape the every day”] leading punters to expect rides, balloons and beer.

Keep your eyes on the wabbit – BOS 2002.

The Biennale of Sydney in 2000 was called Biennale of Sydney 2000 making it a lot easier to spot. It also saw the welcome return of Nick Waterlow and a ‘curatorium’ – a crack team of international curators – producing a well remembered ‘greatest hits’ Biennale that surveyed everything that had happened since 1973. No subtitle? Never mind. Richard Grayson was the artistic director of [The World May Be] Fantastic the 2002 Biennale of Sydney. Aside from the first time inclusion of a parenthetical title in the history of the B.O.S., the exhibition was also the first ever curated by a practicing artist [with ‘advice’ from artists/curators Susan Hiller, Ralph Rugoff and Janos Sugar] Launched by a panel of dignitaries including then Lord Mayor Frank Sartor – a man with an intimate knowledge of the art world – the 2002 BOS was a mixed blessing. Highlights included Mike Nelson’s fake Reptile House in Kings Cross and Simon Paterson’s in-flight instructional video. The downside was a huge array of fake libraries and unwanted references to Borges and Italo Calvino. After two well liked exhibitions, the 2004 BOS On Reason & Emotion was considered a bit of a wash out. Directed by Isabel Carlos, no one could doubt the sincerity of the selection and the presence of Bruce Nauman gave the show some badly needed star power, but much of the show was weak and unfocussed with a theme so opaque no one really understood what it meant.

And that’s the story so far…

Pingback: BOS2010: Themes and Damned Themes |