Was it only last Friday? It seems like an eternity since the Archibald, Wynne, Sulman and Photographic prizes were announced at the Art Gallery of NSW. By now you’ll know that Melbourne painter Marcus Wills won the $35,000 Archibald Prize for The Paul Juarszek Monolith [After Marcus Greenaerts] an unfathomable portrait which takes for its major form a ginormous head taken from an etching by the 17th Century Flemish master Greenaerts. The painting is obscure, highly detailed, painstakingly executed and completely without peer in the rest of the comp. The painting has craft and skill and it’s conceptually odd. As AGNSW trustee Imants Tiller’s told The Australian’s Rosalie Higson, “It was surprisingly easy to agree on the work.” For the captains of industry, media celebrities, doctors and artists on the gallery’s board, it had a little something for everyone.

Vanila Netto’s The magnanimous beige wrap – Part 1 (contraption), winner of the 2006 Photographic Portrait prize. Courtesy Art Gallery of NSW.

Again, we came so close to picking the winner, narrowing the field to three – Will’s painting, Ben Quilty’s architecturally-inspired slab construction of Adam Cullen and Craig Waddell’s portrait of his girlfriend Jesse Cachillo [not the other JC]. Although we felt confident the inscrutable decision making process of the trustees would be a little easier to pick in 2006 with a great Quilty painting shining out among a decidedly drab field, they went and surprised nearly everyone, including the first-time entrant who won the damn thing. As former publicist at the gallery Jan Batten once chastised us, no one can pick the Archibald. We’re happy to advise that one Art Life reader known only as ‘G. Marx” wrote in to tell us: “Hey, congratulations Art Life and punters! What a form Guide! I won fifty bucks on your hot favourite!” If we do nothing else this year, we can be happy that we made someone some money.

John Beard’s Wynne Prize painting The Gap.

Courtesy Art Gallery of NSW

The Archibald and associated prizes generate huge amounts of media – print, television, radio and blogs – but before we discuss the other winners and the art critics reactions to the prizes, we should get our own house in order. Last week we stated that Jason Benjamin had painted John Olsen for the 2005 prize. Andrea Candiani, who works at Metro 5 Gallery, which represents Benjamin in Melbourne, left a comment pointing out that he painted the actor Bill Hunter in 2005 and Olsen in 2004. For some reason the Archibald finalists are starting to blend together in our minds, but apologies to all concerned. We also made the claim last week that McLean Edwards had put himself into the portrait of Cate Blanchett. However, Georgina Bredun was having none of it:

Whoa up there! Exactly HOW has McLean Edwards painted himself into his portrait of Cate Blanchett and her husband, Andrew Upton and their two kiddies, Dashiel and Roman? Last time we looked McLean didn’t have long blonde hair – so it’s not THAT figure. And last time we saw McLean and Upton on the same page (try the current edition of Harpers Bazaar), McLean looked like, well, McLean, and Andrew Upton looked astonishingly like the figure standing behind Cate Blanchett in McLean’s work. Don’t know what’s going on here, but you (Art Life) got it wrong. Big time.

We wrote to Georgina to explain that it was just a joke and that no one would ever seriously accuse Edwards of putting himself in the painting, that it was just a gag. But Bredun did also perhaps inadvertently mention one very salient point – the current issue of Harper’s Bazaar spread featuring photos of Edward’s painting Blanchett. As everyone would know, getting yourself coverage in the media before the judging is curse upon your entry – you simply cannot win. We call it The Curse of Peter Harvey.

And so to the critics. Over at The Australian, Sebastian Smee got two shots at reviewing the Archibald show – one bit in the news section, the other in Inquirer. Like many journalists required to fill a lot of space – and perhaps cut in two by the editors – there was a lot of repetition between the stories.

It was somewhat startling to see that Smee had actually gone to the show. In recent months, he has done just about everything he can to avoid reviewing Australian art. His beat is to travel the world reviewing whatever takes his fancy. His latest piece in Saturday’s Review was posted from London where he wrote about the Martin Kippenberger retrospective at Tate Modern. Since January, he has written ‘think’ prices about Biennales, reviews of the old masters in the Renaissance to Contemporary self portrait show at the AGNSW, the Turkish artist Kutlug Ataman’s show at Sherman Galleries in Sydney, an unforgettable piece on Rembrandt’s drawings and last week the John Constable show at the NGA. The only time Smee has come close to Australian art was a piece on an Indigenous show at the Ian Potter Centre in Melbourne.

If you were only reading The Australian’s chief art critic you would be forgiven for thinking that the commercial and public galleries in this country show nothing but imported exhibitions of overseas artists, most of them dead. No wonder The Australian has to look to Nicholas Rothwell and Ted Snell to take up the slack – Smee wanders the country in search of old masters to eulogise before hitting the books and Google to fill up space with waffle. You can imagine our surprise then when we opened the paper to see that Smee wasn’t much impressed by Wills’s painting:

[The painting] is an elaborate allegory, the meanings of which remain far from clear. The image itself, a giant skull populated by small figures engaged in various activities, is certainly striking, and well painted too. But it is not Wills’s own. He has borrowed it from 16th-century etching and I don’t feel he has done enough with it to convince us that the exercise is worthwhile. Though it can be worthwhile to have one’s idea of portraiture stretched, Wills’s painting does so in a way that affords little insight.

Portraiture can easily grow stale, but it benefits from being the most direct and humanly interesting of genres – to dilute in allegory – and a confusing allegory at that – seems to me to work against its strengths. For what it’s worth, I would have given the prize to John Beard, with Ben Quilty and Tom Carment as runners up.

Reading Smee is like taking a valium and having a lie down. The prose is so leaden and wordy, so long in getting to very modest points, so many fearful qualifications, we now just try to skim over it. Portraiture can grow stale – but perhaps not. I don’t feel he has done enough – but you might disagree. Then there are the mile-wide suppositions – that allegory has to be explicit, that portraiture is humanly interesting, that the artist has to convince us of something. That is just two paragraphs in and already we’re sinking into mud…

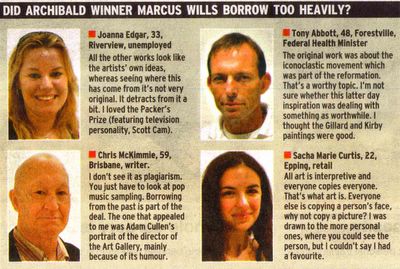

The Sun Herald finds four regular people to interview…

At least Smee doesn’t have a huge axe to grind. The Esteemed Critic at the Sydney Morning Herald however used his three articles on the Archibald to settle a few scores, take a few pot shots and vent spleen. His main piece on the Archibald was written before the announcement, so in place of a discussion of the winner he attacked Cullen – a now annual event – and decry what he sees as the double standards and conflict of interests of the trustees. You’re no doubt saying, ‘what else is new, he does this every year’, and you’d be right. But what was remarkable about John McDonald’s article was the way it revealed the deep contradictions of his reasoning and the hateful invective at the heart of his writing. The title of Quilty’s portrait of Cullen was a launching pad for his interpretation of what Cullen – before and after might mean:

[Quilty’s] subject is a shrewd choice as well. He paints Adam Cullen, the 2000 Archibald winner, as a Jekyll-and-Hyde character. The dark, grinning mug shot on the left is Cullen at his most diabolical, when he was painting pictures of deliberate awfulness, meant to shock and offend viewers and titillate the curators. The right-hand panel shows a more composed character: the respected portraitist, the celebrity. Which is the mask and which is reality?

I suspect both pictures are masks. Cullen strikes me as an artist who is no longer able to draw the line between the self-conscious pose and the inner life. Not even he could say whether his paintings are deliberately bad or simply bad, or simply bad through a lack of competence,

Look, for instance, at his portrait of gallery director Edmund Capon hanging close to the Quilty portrait. Capon resembles a cartoon zombie on a decorator’s backdrop of duck-egg blue-grey. This is, of course, meant to be a shocking image of someone we know as worldly and sophisticated. The blank eye sockets are the real key; eyes are hard to paint, so it’s easier to leave them out. If this makes the image even weirder, well that’s a bonus.

Where McDonald perceives an artist who he thinks is celebrated for the wrong reasons, it must therefore be because they can’t paint. This is ridiculous. Cullen doesn’t paint any buttons on Capon’s shirt – so he mustn’t be able to paint them either. Or hands. Or hair. If McDonald likes an artist it is invariably because they have demonstrable craft skill, be it traditionalists like Jiawei Shen or contemporary artists like Ricky Swallow. The whole idea of artists making choices seem to be an alien concept to McDonald. This non logic suggests that abstract painters can’t paint figures, photographers can’t draw, video artists can’t sculpt, performance artists can’t make ceramics – yes, we know – those are probably just statements of fact – but it has no bearing on their practice and besides, maybe they made a choice to make art in a certain way?

Jiawei Shen’s Sulman winner Peking treaty 1901, judged by Janet Laurence.

Courtesy Art Gallery of NSW

It’s a little hard to tell whether McDonald is seriously arguing this position or is just taking a cheap sarcastic shot, but it soon became apparent that Cullen’s portrait of Capon was a finalist was because there is a conspiracy:

When Jiawei Shen painted Edmund two years ago, the painting was omitted from the Archibald, presumably because of the possible conflict of interests. (Capon is one of the judges.) No one could credibly claim that Cullen’s portrait is superior to Shen’s effort, so it seems that times and policies have changed. This year, not only do we have a portrait of Capon, but one of Lindy Lee, a recent appointment to the Board of Trustees. If this painting were a masterpiece there might be some excuse, but it is a very ordinary likeness by Bin Xie, one of the subject’s former students from Sydney College of the Arts. The right-hand panel is a gooey little note telling us what a lovely person Lindy is and what a nice smile she has. We all know that the gallery sees the Archibald as pure showbiz, a bit of a laugh at Easter time, but it’s pathetic when the trustees are cluttering the exhibition with second-rate images of themselves, perhaps at the expense of more significant work. A lot of artists take this exhibition very seriously; putting heart and soul into their entries. One can imagine how they feel to see their paintings tossed out, while the trustees have their fun putting together a piece of popular entertainment.

It should no doubt make McDonald happy that Jiawei Shen won the Sulman prize for his lugubriously demonstrative and allegorical painting Peaking Treaty 1901. As to the rest of his argument, McDonald makes some mighty big suppositions – for example, that presumably Shen’s portrait of Capon wasn’t a finalist because of conflict of interest issues – or that no one could credibly claim that Cullen’s portrait was better than Shen’s. Well, maybe the reason Shen’s portrait didn’t get in was because it wasn’t very good? And that Cullen’s was hung because it was? McDonald is right to say that Bin Xie’s portrait is horrible, but there’s no evidence that more significant work was excluded, as the Salon des Refuses inevitably proves every year. McDonald’s syle is to throw enough mud and see what sticks – appeal to the artists who were excluded, suggest corruption and self interest, mock the finalists. He really ought to start his own blog.

Critiquing the critics! That’s what I call overkill.